authorship, writing, printing, publishing, and reading

Book history is one of the most recent and interesting branches of literary studies. It asks questions such as ‘What is a text?’, ‘What is a book?’, and ‘How do we read?’ The answers to these questions are much more complex than you might imagine. David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery start An Introduction to Book History by outlining the main theories and critical debates that have informed book history studies over the last hundred years.

It’s amazing how many different fields of study this leads to – the physical production of texts; how accurate they are; what they ‘mean’; and how they are interpreted by readers. These same questions of authorship, textual integrity, and the unique nature of a work also apply in other art forms.

It’s amazing how many different fields of study this leads to – the physical production of texts; how accurate they are; what they ‘mean’; and how they are interpreted by readers. These same questions of authorship, textual integrity, and the unique nature of a work also apply in other art forms.

In cinema, music, theatre, and television there may even be interventions from other hands. But it is writing and especially printing which are at the heart of the most important intellectual developments of the modern world, and to which they devote their first two introductory chapters. Much of their argument rests on the work of previous historians of the book and literacy, writers such as Walter Ong, Henri-Jean Martin, and Elizabeth Eisenstein.

They trace the changing role of the writer – from anonymous religious copyist in the early Renaissance, and authors working under systems of courtly patronage, to the modern concept of a creative independent working in the free commercial market supplying literary products and services.

Next comes a consideration of the practical aspects of what happens after a manuscript leaves the author. Printers, book distributors, publishers, readers, and even agents. All of these, they argue, can all affect a text; and they should certainly be seen as part of the context out of which the text arises.

Then they move on to consider what has been described as the ‘missing link’ in book history – the reader. For as many theorists have argued, the text exists in a state of potential whilst it remains as words printed on a page: it only springs into a life of real meaning when it is interpreted in the reader’s mind.

Why therefore aren’t there as many different interpretations of a text as there are different readers – all equally valid? Well, the answer to this conundrum is supplied by Stanley Fish when he comes up with the notion of ‘interpretive communities’. People sharing cultural values are likely to interpret the text in the same way.

They end by looking at the future of books and readers, An interesting detail here is that despite all the prophets of doom, a greater number of books are being read than ever before – but by fewer readers.

I was hoping for a little more on the book as a physical object, and I think longer consideration of digital literature on line might have informed their arguments. But they provide a comprehensive critical introduction to the development of the book and print culture.

© Roy Johnson 2005

David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery, An Introduction to Book History, Abingdon: Routledge, 2005, pp.160, ISBN: 0415314437

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

This tutorial looks at the famous opening passage of Bleak House and examines Dickens’s use of language, simile, and metaphor. It argues that whilst Dickens is often celebrated for the vividness of his descriptions, the true genius of his literary power is in imaginative invention.

This tutorial looks at the famous opening passage of Bleak House and examines Dickens’s use of language, simile, and metaphor. It argues that whilst Dickens is often celebrated for the vividness of his descriptions, the true genius of his literary power is in imaginative invention. This is the first of two close reading tutorials on Conrad’s early tale An Outpost of Progress. This one looks at the opening of the story and examines the semantic values transmitted in Conrad’s presentation of the narrative. That is, how the meaning(s) of the story are embedded in even the smallest details of of the prose.

This is the first of two close reading tutorials on Conrad’s early tale An Outpost of Progress. This one looks at the opening of the story and examines the semantic values transmitted in Conrad’s presentation of the narrative. That is, how the meaning(s) of the story are embedded in even the smallest details of of the prose. This tutorial looks at one of the opening paragraphs of Katherine Mansfield’s short story The Voyage. It covers the standard features of a writer’s prose style – in the use of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, tone, narrative mode, and figures of speech; but then it singles out the crucial issue of point of view for special attention. Mansfield was one of the only writers to establish a first-rate world literary reputation on the production of short stories alone.

This tutorial looks at one of the opening paragraphs of Katherine Mansfield’s short story The Voyage. It covers the standard features of a writer’s prose style – in the use of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, tone, narrative mode, and figures of speech; but then it singles out the crucial issue of point of view for special attention. Mansfield was one of the only writers to establish a first-rate world literary reputation on the production of short stories alone. Virginia Woolf used the short story as an experimental platform on which to test out her innovations in language and fictional narrative. This tutorial offers a detailed reading of the whole of the experimental story Monday or Tuesday. It shows how its mixture of lyrical images, speculative thoughts, and fragments of story-line add up to more than the sum of its parts.

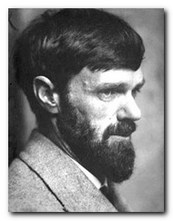

Virginia Woolf used the short story as an experimental platform on which to test out her innovations in language and fictional narrative. This tutorial offers a detailed reading of the whole of the experimental story Monday or Tuesday. It shows how its mixture of lyrical images, speculative thoughts, and fragments of story-line add up to more than the sum of its parts. D.H.Lawrence was the first world-class writer to have emerged from the working class. His work was passionate, sensual, and controversial. This tutorial looks at the opening paragraphs of his short story Fanny and Annie published in 1922. It considers in particular his use of the rhetorical devices of repetition and alliteration to impart a poetic impressionism to his writing.

D.H.Lawrence was the first world-class writer to have emerged from the working class. His work was passionate, sensual, and controversial. This tutorial looks at the opening paragraphs of his short story Fanny and Annie published in 1922. It considers in particular his use of the rhetorical devices of repetition and alliteration to impart a poetic impressionism to his writing.