tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

The Sacred Fount was first published simultaneously as a single volume by Charles Scribners and Sons in New York and Methuen in London in February 1901. It comes from the ‘late period’ in James’s development as a novelist, and has puzzled readers and critics ever since, because of the obscurity of its subject matter and the extremely complex manner in which the events are related.

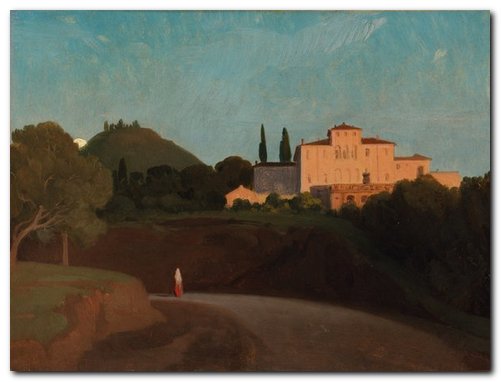

On the surface, it is the simple story of a number of people who travel to a weekend party at a country estate (Newmarch). But the narrator of events perceives hidden relations going on between some of the visitors – and he tries to work out the truth of these liaisons by psychological means alone, eschewing what he calls the ignoble methods of “the detective and the keyhole”.

The Sacred Fount – critical commentary

The original idea

When he first began writing The Sacred Fount Henry James thought the narrative would take the form of a short tale – as he did with many of his other novels – most of which became anything other than short. This is how James described what he called the donnée of his tale.

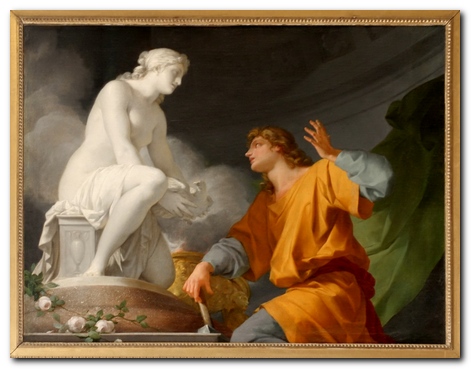

The notion of the young man who marries an older woman and who has the effect on her of making her younger and still younger, while he himself becomes her age. When he reaches the age that she was (on their marriage) she has gone back to the age that he was.

Mightn’t this be altered (perhaps) to the idea of cleverness and stupidity? A clever woman marries a deadly dull man, and loses and loses her wit as he shows more and more.

Both of these ideas are incorporated into the novel. The Narrator thinks Guy Brissenden’s vital juices are being drained by May Server or Lady John, leaving him looking much older than his twenty-nine years. They on the other hand appear much younger and more vivacious than their middle-age would suggest.

Gilbert Long on the other hand has always been something of a nonentity and dolt, but has suddenly developed intelligence and wit – as a result (it is supposed) of his secret sexual relationship with a clever woman. The Narrator spends the next three hundred pages trying to uncover the identity of this women.

‘The Sacred Fount’ as a concept is the source of youth at which older people are refreshing themselves – draining vital fluids from their younger partners. It is easy enough to spot here the notion of vampyrism which has influenced a lot of critical comment on the novel – the older person feeding off the life forces of someone younger, or the same thing in intellectual terms.

Problems of interpretation

The main problem with this as the plot for the novel is the reader is at no point presented with any impartial evidence or dramatised interchanges between the characters on which to form an independent judgement about such matters.

If fact one of the major weaknesses associated with the novel is the lack of characterisation. People are named perhaps given an age – and that’s it. There is no way a reader can form a picture or make any distinction between Grace Brissenden or May Server. They are both either ‘very beautiful’ or look younger than they did previously. Similarly, the men are merely names – Gilbert Long, Guy Brissenden, and Ford Obert. Who might be relating to whom is left unrecorded – except in the Narrator’s overheated imagination.

Not only are the characters not developed as fictional constructs, but everything in the narrative is mediated by the un-named, first-person Narrator. He tells us about the appearance and the interchanges between the other characters – so at a very simple, technical level, we only have his opinion or his interpretation of events.

But more than this, it rapidly becomes apparent that he is one of James’s unreliable narrators – not unlike the Governess in The Turn of the Screw (1898) written three years earlier.

The other characters do not see or do not agree with his observations. He actually imagines, invents, and ‘constructs’ other people’s conversations – thinking what the might or could be saying to each other. But then he draws his analytic conclusions from this evidence that he has constructed himself.

When the Narrator challenges and quizzes people about his suppositions, they give their own account or opinions of events – which turn out to be the exact opposite of what he suspects.

The Narrator is entirely self-congratulatory and vain: he describes himself as having ‘transcendent intelligence’ and ‘superior vision’ – yet the fact is that nobody else agrees with claims he is making, and of course at the end of the novel he turns out to be wrong.

The Narrator puts all his arguments in the form of elaborate metaphors, obscure allusions, and extravagant figures of speech. His interlocutors repeatedly ask him what he is talking about, and Mrs Brissenden finally tells him she thinks him crazy.

He even tells lies – for instance, claiming to Mrs Brissenden that he has not discussed with other people the issues of the secret liaisons he suspects – when in fact he has discussed them with just about everyone else he meets.

Rebecca West issued one of her wittiest sneers when she wrote that the narrator “spends more intellectual force than Kant can have used on The Critique of Pure Reason in an unsuccessful attempt to discover whether there exists between certain of his fellow-guests a relationship not more interesting among these vacuous people than it is among sparrows.”

Leon Edel described the novel as “a detective story without a crime—and without a detective. The detective, indeed, is the reader.”

The Sacred Fount – study resources

![]() The Sacred Fount – Library of America – Amazon UK

The Sacred Fount – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() The Sacred Fount – Library of America – Amazon US

The Sacred Fount – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Sacred Fount – Kindle edition

The Sacred Fount – Kindle edition

![]() The Sacred Fount – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

The Sacred Fount – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Sacred Fount – audiobook at Librivox

The Sacred Fount – audiobook at Librivox

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James – biographical notes

Henry James – biographical notes

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

The Sacred Fount – plot summary

Chapter 1. The Narrator travels by train to a country weekend party at Newmarch with Gilbert Long, and Mrs Grace Brissenden, commenting on the changes in their appearance. Mrs Brissenden thinks that the changes to Gilbert Long are the result of his relationship with Lady Jane.

Chapter 2. The Narrator sees Lady Jane with Gilbert Long at Newmarch. He also meets Guy Brissenden, Grace’s much younger husband, and is astonished at how much older he appears – whereas his wife looks much younger. However, when he discusses these changes with Gilbert Long, his friend does not see them at all. The Narrator theorises that the older person in a couple can become younger – but only at the expense of the younger partner becoming older.

Chapter 3. The Narrator discusses his theory with Mrs Brissenden and the case of Gilbert Long and Lady John, where he thinks there he thinks there has been a transfer of intelligence, making him the cleverest guest but one [the cleverest by implication being the Narrator himself]. He suggests that they should search out the biggest fool at the party to discover the source of Long’s improvement – but there must be evidence of relations between them. They make further observations which prove fruitless, and the Narrator entertains the notion that his suppositions might be in bad taste.

Chapter 4. Mrs Server thinks that Lady John is only interested in Ford Obert. The Narrator and May Server discuss a painting of a man holding a mask, guessing of whom it reminds them. The Narrator talks with Ford Obert about his theory, who has similar suspicions of Mrs Server. They agree to limit their observations to psychology alone, yet they recognise that theoretically it’s none of their business which other parties in these presumably illicit relations are creating the effects they claim to be observing.

Chapter 5. The Narrator discusses with Mrs Brissenden their observations regarding Mrs Server. They disagree, and still have no evidence for their claims and no known lover. They go out into the garden and find Mrs Server with Guy Brissenden. His wife claims that he is being used as a red herring by Mrs Server to deflect attention from her real lover.

Chapter 6. The Narrator reflects that whilst Mrs Server keeps appearing with different men, he himself is not one of them. He wonders briefly if he might be in love with her, and if the rest of the company are wondering about her as he is. Next he comes across Lady John and Guy Brissingham in a remote part of the gardens. He imagines their thoughts and intentions regarding each other, and concludes that Lady John is using Guy Brissenden as a red-herring too.

Chapter 7. The Narrator quizzes young Guy Brissenden on Lady John and Mrs Server, but Brissenden contradicts every one of his suppositions. They agree that Mrs Server is very happy, but don’t know why. Guy Brissenden wants to ‘help’ Mrs Server, and thinks she might be hiding something. He asks the Narrator to help him find out what it is, but the Narrator refuses without giving any explanation.

Chapter 8. The Narrator congratulates himself on the accuracy and the success of his observations. He then meets Mrs Severn in a garden. They barely speak to each other about the ideas that concern him – which he interprets as a sign that she wants a respite from the strain of acting a part of gaiety. When they do speak it seems to be at cross purposes, about different people – which he interprets as a cover for the truth he thinks she is hiding. He tells Mrs Server directly that he believes Guy Brissenden is in love with her. , by whom they are shortly joined. The Narrator makes his excuses and leaves them together.

Chapter 9. After dinner that night the Narrator talks with Gilbert Long, congratulating himself that he knows Long’s secret (and that Long knows that he knows) but they cannot discuss it openly. A visiting pianist gives a recital, during which the Narrator assumes that all the guests are reflecting privately on the relationships he thinks he has uncovered. He then challenges Lady John, but she answers him in an oblique manner. When she asks him who he is so concerned about, he refuses to answer her. Moreover, he believes that Lady John does not and can not know all the subtle connections between the guests which he perceives.

Chapter 10. As a return to London is in prospect for the next day, the Narrator wonders if all the changes and effects he has observed in the guests might disappear and everything return to normal. By midnight he resolves to escape the problems of analysis by leaving on an early train next morning. But then seeing Gilbert Long alone on the terrace all his curiosity is re-awakened. He then meets Ford Obert and goes in search of Mrs Brissenden who has promised to have a word with him.

Chapter 11. He follows Obert into the library, where he challenges him directly about his interest in Mrs Server. They agree that she has changed, but Obert claims she has reverted to an earlier state of being. Obert claims he has been watching the Brissendens and has reached to same conclusions as the Narrator. However, the Narrator will not accept this admission because he believes that Obert cannot have all the relevant ‘information’. They agree that Mrs Server’s lover may not actually be there at the house. Suddenly Guy Brissenden arrives to say that his wife want to speak to the Narrator, who thinks that maybe Gilbert Long and Mrs Brissenden have been or still are lovers.

Chapter 12. When he meets Mrs Brissenden she looks very young, and he hopes that all will be revealed. But she has nothing of any consequence to tell him. In fact she expects him to make all the revelations. But she does believe that May Server is not involved in the puzzle they have been trying to solve. The Narrator is suddenly quite sure that Gilbert Long is Mrs Brissenden’s lover and that she is protecting him. He challenges her to say who has brought about the remarkable change in Long. In response, she accuses him of being too fanciful and over-analytical.

Chapter 13. When she singularly gives him no concrete information, he interprets this as proof that he is correct in his suppositions. He then invites her to advise him how to get rid of his over-active imagination (which he believes has led him to the truth) – but this is a trick designed to get her to reveal her ‘secret’. But she suddenly declares that she thinks him crazy. He then interrogates her relentlessly about exactly which point in the day she changed her mind about him. Finally she reveals that Gilbert Long has been the centre of her attention – but only as a negative example of the Narrator’s idea of a stupid person being elevated intellectually by a romantic liaison. She declares that Gilbert Long was not transformed at all: he was always stupid and remains so now.

Chapter 14. The Narrator is forced to admit that his theory was all wrong. However, Mrs Brissenden admits that she has been lying and covering up – and that Lady John is the woman in question. Her husband has revealed to her the liaison between Long and Lady John. The Narrator concludes their lengthy nocturnal debate and goes to bed chastened.

The Sacred Fount – principal characters

| I | the un-named narrator |

| Newmarch | the country estate where the weekend party takes place |

| Gilbert Long | a visitor at the party |

| Mrs Grace Brissenden | a woman of 42 |

| Guy Brissenden | her husband of 29 |

| Lady John | a visitor at the party |

| Ford Obert | a painter |

| Mrs May Server | an attractive weekend visitor |

| Lord Luttley | a weekend visitor |

| Compte de Dreuil | French visitor |

| Comptess de Dreuil | his American wife |

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biography

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Henry James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended. Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness Nostromo

Nostromo

Lord Jim

Lord Jim

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad  Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes Chance

Chance

Between the Acts

Between the Acts The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield

Nadine Gordimer

Nadine Gordimer

Washington Square

Washington Square

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.