politics, life, and literature 1911-1969

Leonard Woolf is probably best known as the husband of Virginia Woolf, but in fact he had a remarkable life and set of achievements quite apart from his wife. He was a political activist and one of the founders of the League of Nations (which became the United Nations); he was a novelist and a journalist; and throughout the whole of his adult life he was a professional publisher, in charge of the very successful Hogarth Press, which he founded and ran successfully for fifty years.

The first volume of his autobiography dealt with his childhood in a prosperous upper middle-class Jewish family and his early memories of growing up in late Victorian London, then his intellectual flowering when he went to Cambridge. The are some wonderful character sketches of his contemporaries, who became luminaries of the Bloomsbury Group, including Saxon Sydney Turner, Lytton Strachey, and Clive Bell.

The first volume of his autobiography dealt with his childhood in a prosperous upper middle-class Jewish family and his early memories of growing up in late Victorian London, then his intellectual flowering when he went to Cambridge. The are some wonderful character sketches of his contemporaries, who became luminaries of the Bloomsbury Group, including Saxon Sydney Turner, Lytton Strachey, and Clive Bell.

He comes across as a thoroughly decent, intelligent, hard-working man, with a particularly sharp eye for the underdog and a love of animals which makes him an animal liberationist before his time. His experiences in Ceylon made him increasingly anti-imperialist, so he quit the service in 1911 and married Virginia Woolf instead.

This second volume covers his astonishingly rich and varied life post 1912 – engagement with the co-operative movement, a gradual shift to the Left in political terms, and friendships with all the leading literary and political figures of the day – H.G.Wells, G.B.Shaw, Bertrand Russell, Ramsay MacDonald, and T.S.Eliot. There are also sustained portraits of Ottoline Morrell, Isobel Colefax, Sigmund Freud (whose complete works he published) and Ramsay MacDonald. He also provides an impassioned account of the political dark years of the 1930s.

Politically, he was a left-wing realist. He served on endless committees, fighting for causes in which he believed. Yet he realised that the people amongst whom he worked, and the mechanisms they pursued, were deadly boring. Unlike many fellow travellers of the inter-war years, he was also well aware that the communists (in Soviet terms) killed more people than they helped or saved.

He’s very revealing on the mechanics of running a small independent publishing company, and he presents the profits and balance sheets of the Hogarth Press with the very conscious aim of revealing what most other writers talk about but never confess – how much they make from their writing.

In the last part of his memoir, written when he was eighty-five, it has to be said that he rambles quite a lot, and goes over ground he has already covered earlier. But this does help to reinforce the tremendous variety in his life. He felt that all his political efforts amounted to nothing, and that the Hogarth Press had been successful because it had been kept small scale and independent. He’s probably a bit too hard on himself politically, and anybody with a CV half as long could hold their head up high.

However, this is not a memoir full of gossip or personal revelation. You would never know from this that his wife fell in love with another woman, or that he had a largely sexless relationship with her. Nor would you ever guess that for the last thirty years of his life he shared the wife of his business associate on a weekend-weekday basis.

As an autobiography, it’s long overdue for a reissue, but in the meantime, the two volume Oxford Paperbacks edition offers the full text with good indexes. Leonard Woolf went up in my estimation as a result of reading this memoir, and I am looking forward now to both his collected leters, and in particular to the letters he exchanged on almost a daily basis with his ‘lover’ Trekkie Parsons.

© Roy Johnson 2000

![]() See volume one of this autobiography

See volume one of this autobiography

Leonard Woolf, An Autobiography: 1911-1969 v. 2, Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks, 1980, pp.536, ISBN: 0192812904

More on biography

More on Leonard Woolf

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Leonard Sidney Woolf was born in London in 1880, the third of ten children of Solomon Rees Sydney and Marie (de Jongh) Woolf. When his father died in 1892, Woolf was sent to board at the Arlington House School, a preparatory school near Brighton. From 1894 to 1899 he studied on a scholarship as a day student at St. Paul’s, a London public school noted for its classical studies. In 1899 he won a classical scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge.

Leonard Sidney Woolf was born in London in 1880, the third of ten children of Solomon Rees Sydney and Marie (de Jongh) Woolf. When his father died in 1892, Woolf was sent to board at the Arlington House School, a preparatory school near Brighton. From 1894 to 1899 he studied on a scholarship as a day student at St. Paul’s, a London public school noted for its classical studies. In 1899 he won a classical scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge.

He became an Anglican clergyman, but in 1865 renounced his religious beliefs and left the church. In 1869 he married Harriet Thackeray, the daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray. They had a daughter Laura (1870-1945) who developed a form of incurable brain disease and was institutionalised for the majority of her life. When his wife died rather suddenly in 1875 he married Julia Prinsep Jackson, the widow of Herbert Duckworth. She brought with her two sons, George and Gerald, the latter of whom went on to found the Duckworth publishing company.

He became an Anglican clergyman, but in 1865 renounced his religious beliefs and left the church. In 1869 he married Harriet Thackeray, the daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray. They had a daughter Laura (1870-1945) who developed a form of incurable brain disease and was institutionalised for the majority of her life. When his wife died rather suddenly in 1875 he married Julia Prinsep Jackson, the widow of Herbert Duckworth. She brought with her two sons, George and Gerald, the latter of whom went on to found the Duckworth publishing company.

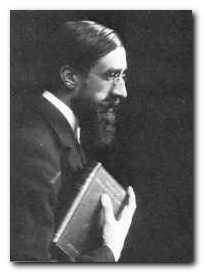

Lytton Strachey (1880-1932) was born at Clapham Common and raised at Lancaster Gate, in central London. He was the eleventh of thirteen children, to General Sir Richard Strachey (an engineer) and his wife Jane Grant. Though he spent some years at boarding schools, including Abbotsholme and Leamington College, he received much of his education at home. His mother took an interest in literature and politics, and Strachey met many of the leading writers and thinkers of the day when they came to visit Lady Strachey. His secondary education was completed at University College in Liverpool where he studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, and English literature and history. It was there that he met and was influenced by Walter Raleigh, a professor of English literature and well known biographer.

Lytton Strachey (1880-1932) was born at Clapham Common and raised at Lancaster Gate, in central London. He was the eleventh of thirteen children, to General Sir Richard Strachey (an engineer) and his wife Jane Grant. Though he spent some years at boarding schools, including Abbotsholme and Leamington College, he received much of his education at home. His mother took an interest in literature and politics, and Strachey met many of the leading writers and thinkers of the day when they came to visit Lady Strachey. His secondary education was completed at University College in Liverpool where he studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, and English literature and history. It was there that he met and was influenced by Walter Raleigh, a professor of English literature and well known biographer.

Strachey’s Letters

Strachey’s Letters

He worked as a secret agent, using multiple identities and the cover of a job as journalist and editor. His real job there was to assist the promotion of the German Revolution ‘planned’ for October 1923. This was a period when Marxist orthodoxy thought that revolutions could be planned and organised according to theoretical principles, without troubling to analyse or face any social facts. When the revolution failed to take place, he de-camped to Prague. However, even though conditions there were less severe, he felt unable to act effectively, and so, as a Trotsky supporting oppositionist and at the worst possible time, he loyally returned to Leningrad in 1926.

He worked as a secret agent, using multiple identities and the cover of a job as journalist and editor. His real job there was to assist the promotion of the German Revolution ‘planned’ for October 1923. This was a period when Marxist orthodoxy thought that revolutions could be planned and organised according to theoretical principles, without troubling to analyse or face any social facts. When the revolution failed to take place, he de-camped to Prague. However, even though conditions there were less severe, he felt unable to act effectively, and so, as a Trotsky supporting oppositionist and at the worst possible time, he loyally returned to Leningrad in 1926. life, works, political persecution

life, works, political persecution The Master and Margarita

The Master and Margarita