tutorial, study guide, commentary, further reading, web links

Two on a Tower was first published by Sampson Low, London, in three volumes in 1882. it was written between two of Thomas Hardy’s major novels – The Return of the Native in 1878 and arguably his greatest work The Mayor of Casterbridge in 1886 – though it has to be said that he produced a number of other minor works around this time, such as The Trumpet Major (1880) and A Laodicean (1881). Hardy called the novel a ‘romance and a fantasy’, but there seem no valid reasons why it should not be judged by the same criteria as those used to assess his other works.

Two on a Tower – commentary

The sensation novel

The sensation novel was a literary genre developed in the mid nineteenth century by writers such as Wilkie Collins and Mary Elizabeth Braddon. They created plots that were designed to ‘jolt the reader’ (John Sutherland’s term) with elements of secret marriages, forged wills, bigamy, blackmail, murder, concealed identities, and other elements inherited from the late eighteenth-century Gothic – such as fraud, theft, kidnapping, and incarceration.

Thomas Hardy is not normally regarded as a novelist of the ‘sensationalist’ school, but there are certainly many elements of its literary devices in his work. Two on a Tower features several plot devices that span the melodrama and the sensation novel.

The relationship between the protagonist Swithin and Lady Viviette Constantine is presented as ‘peculiar’ because of the age difference and the apparent disparity in their status. Yet she is only eight years older than him; she has married into her position of Lady Constantine; and he is the son of a clergyman. They are not so far apart socially.

This age difference might seem inconsequential to readers today – but in the late nineteenth century it was considered somewhat risque to have a mature (and formerly married) woman making what are clearly sexual overtures to a young male.

The sudden arrival of unexpected news is also a favourite device of the sensation novel. On the very day that Swithin is setting off to secretly marry Viviette he receives an inheritance, but only on the condition that he remain single. On virtually the same day Viviette also receives a letter from her brother Louis Granville (who has not been mentioned in the novel up to that point) announcing his arrival to thwart her romance.

Bigamy

But the most glaring element of sensationalism is the fact that Swithin and Viviette enter into a secret marriage. The reasons for secrecy are bound up with the complex socio-economic issues arising from their perceived difference in status – which Hardy does not fully explain or justify. The secret provides a dramatic element to the events that follow – but the more significant issue is that the marriage remains unconsummated for quite some time.

Moreover, there are not just one but two instances of bigamy in the novel. When Swithin and Viviette get married in secret, they do so believing that Sir Boult Constantine is dead- from disease contracted during his African lion hunt. But the report is what we might currently call false news – so for quite some time Viviette is married to two men – Swithin and Sir Boult.

This is perhaps the main reason Hardy leaves her second marriage unconsummated for so long. Public moral attitudes might not (probably would not) have tolerated both technical bigamy and what would have been seen as sexual pluralism at that time. This voluntary state of chastity also stretches the reader’s credulity – almost to breaking point.

It subsequently turns out that Sir Blount has indeed died – but at a much later date than that reported. So the secret marriage between Swithin and Viviette remains invalid, because at the time of its being registered Viviette was not free to marry someone else.

But this revelation allows Hardy to introduce another sensationalist element into the plot. Sir Blount has not died of typhoid or any other tropical disease. He too has committed a form of bigamy by taking an African ‘wife’ whilst still married to Viviette – and then he has subsequently committed suicide in what we take to be a fit of existential despair.

Indeed, Viviette comes close to being a double bigamist – because she marries Swithin whilst her first husband is still alive. Later, having learned that her first husband is now dead, she consummates her marriage to Swithin, but then after he leaves for South Africa she marries the Bishop of Melchester – whilst she is pregnant with Swithin’s child.

The final twist

Close followers of Hardy’s psychology and his attitude to women and human relationships will notice a double twist at the end of the novel. Swithin returns from South Africa to be confronted by Viviette as the ‘older woman’. She is only in her early thirties, but is described as being in her ‘worn and faded aspect’. She has also had by this point two former husbands. Swithin realises with horror he no longer loves her – but out of a sense of loyalty he offers to marry her. She spares him the ordeal by dying on the spot

But his neighbour Tabitha Lark has meanwhile conveniently matured into ‘blushing womanhood’ and is not only a trained musician but someone ready to help him transpose his astronomical notes. In other words, she is a younger wife ready and in waiting.

So just as Angel Clare goes off with Tess d’Uurberville’s younger sister after his wife is hanged for the murder of Alec d’Urberville, Hardy has a ‘solution’ to the problem on hand that reveals a great deal about his own unconscious and not-so-unconscious wishes – and one which he was to act out in his own troubled life with such unhappy consequences.

Hardy had a largely unhappy marriage, but following the death of his first wife Emma, he married the much younger woman Florence Dugdale – who was forty years his junior. Unfortunately for him this marriage also turned out to be unsatisfactory, and Hardy spent the next sixteen years expressing his remorse in poems dedicated to his first wife.

Symbolism

It is possible to see Swithin’s interest in astronomy as a metaphor for intellectual ambition and his yearning for a world beyond everyday existence in a provincial backwater of south-west England. But a more obvious instance of symbolism is the Tower itself and the telescopes used in his observations.

Almost all the romance between Swithin and Viviette is conducted on the clearly phallic tower – which even acquires a ‘dome’ during the course of events. It is Viviette who supplies Swithin with an object lens for his telescope when he rather clumsily breaks the one he has just bought. She also supplies the ‘equatorial mount’ – a device for synchronising the telescope with the earth’s axis of rotation.

Given that Swithin and Viviette spend the greater part of the novel in an unconsummated ‘union’, the tower and the telescopes act as suggestive symbolic parallels to their relationship

A weakness?

Swithin St Cleve is devastated to find that someone has made the same astronomical discovery as himself and published a scholarly paper on the matter. He collapses during a rainstorm, catches a chill, and is thought to be near the point of death. However, his spirits rise and he recovers on hearing news of the arrival of a comet – which he observes through his new ‘equatorial’ telescope.

Now of all the people in a remote rural location who would know about the arrival dates and visibility of comets – it would be an astronomer. Yet we are led to believe that this occurrence is some form of therapeutic surprise to Swithin. In addition, the comet appears to be visible for not just a number of days, but for months – which is uncommon to the point of extreme improbability. It is not like Hardy to make mistakes of this magnitude in his work.

Geography

Almost all the events of the novel take place in an unspecified location in the south-west of England. But apart from mention of Bath, Southampton, and Melchester (Salisbury) there is very little attempt on Hardy’s part to integrate his narrative with the world of ‘Wessex’ that is built up so powerfully in his other novels.

In novels such as The Return of the Native (1876), The Woodlanders (1887), and Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) the landscape of Wessex is not only densely realised and vividly evoked; it becomes part of the narrative of events itself.

Egdon Heath presides over all the events of The Native with a brooding intensity. The woods, forests and coppices provide not only the background to events but the livelihoods of characters in The Woodlanders. And Tess is forced to work on the land as an agricultural labourer because of her tragic circumstances.

This sort of close relationship between the geography of the region and the events of the narrative simply do not exist in Two on a Tower. There is very little reason to believe that the events of the novel take place imaginatively within the boundaries of Hardy’s traditional ‘Wessex’.

Two on a Tower – study resources

![]() Two on a Tower – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Two on a Tower – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Two on a Tower – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Two on a Tower – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Two on a Tower – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

Two on a Tower – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Two on a Tower – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

Two on a Tower – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

Two on a Tower – plot synopsis

I. Lady Constantine explores the memorial tower on her husband’s estate She meets the beautiful young man Swithin St Cleve who is studying astronomy

II. Members of the local choir assemble for practice at Grandma Martin’s house. Tabitha Lark reports on Lady Constantine’s listlessness. Her husband Sir Blount Constantine is missing in Africa. Swithin hides upstairs in the house.

III. Lady Constantine asks parson Torkingham’s advice on her vow to remain socially secluded during her husband’s visit to Africa. She agrees to maintain her vow.

IV. Lady Constantine visits Swithin on the tower. He describes astronomy in emotive terms.. She asks him to check on Sir Blount who has been seen in London.

V. The person on London is not Sir Blount. Swithin breaks his new object lens, but Lady Constantine replaces it. She cuts off a lock of his hair whilst he is asleep.

VI. Swithin’s new telescope doesn’t work, but Lady Constantine agrees to buy him an ‘equatorial’ viewing instrument. The new project energises her.

VII. She decides to buy the new instrument for herself, and let him have use of it. But local gossip about their relationship begins, so she puts the whole project into his name.

VIII . She pays over the money for the instrument in secret then visits the new telescope at night with Swithin. She feels he is losing himself in the stars.

IX. Swithin makes a new astronomical discovery, but then finds that someone else has just published the same results. He falls ill, and when Lady Constantine goes to visit him he is thought to be dying.

X. Swithin’s spirits are revived by the arrival of a comet. Lady Constantine follows the news of his recovery at a distance.

XI. Lady Constantine feels guilty about her romantic yearning for Swithin, and she vows to both deny herself and find him a suitable wife. At this very point Torkinham reveals that her husband died some time ago in Africa.

XII. Sir Blount dies leaving his estate in debt. Much of his estate is sold off, and Lady Constantine is left in relative poverty. She goes to the tower and reveals her position to Swithin, wondering why he is so matter-of-fact in his response.

XIII. They try to leave the tower, but are obstructed by the arrival of the rustics, who discuss Lady Constantine, Swithin, and the possibilities of a marriage. Swithin is shocked by what he overhears.

XIV. The new knowledge inflames his passion, but when they meet she feels guilty at distracting him from his astronomy They think their relationship cannot succeed, and must be concealed from the general public.

XV. Three months later they meet on the tower again. . He proposes a secret marriage, which will only be revealed when he becomes ‘famous’. In the meantime, they will continue to live separately. She agrees to the proposal.

XVI. A sudden gale blows the protective dome off the tower and the gable end off his grandmother’s house. Plans are changed. She will go to Bath and arrange a marriage license. She gets a letter announcing the arrival of her brother from South America.

XVII. Lady Constantine goes to Bath and despite her fears and misgivings she arranges a marriage license – though she is two days short of qualification.

XVIII. Swithin sets out to join her in Bath, but the same morning he gets notice of an inheritance from his great-uncle. However, it stipulates that he must not marry before reaching twenty-five. He ignores the offer and sets off.

XIX . They meet in Bath and after delays are married. But Viviette’s face is cut by a horse whip at the station – brandished by her brother. Fearing they will be recognised and exposed, they hide out in the Tower hut.

XX. They observe the Aurora Borealis from the Tower, then the next day she goes back home.

XXI . Swithin visits Viviette secretly at her home. She shows him round the house, and persuades him to be confirmed in church.

XXII. Viviette’s brother Louis Glanville suddenly arrives at the house. Swithin hides, then leaves dressed in an old coat of Sir Blount’s. The rustics meet him on the way back and think they have seen a ghost.

XXIII. Winter comes and goes. Viviette refurbishes the house in preparation for the forthcoming confirmation ceremony.

XXIV. The confirmation ceremony takes place, during which Louis watches Swithin very closely.

XXV. The visiting bishop is an old friend of Swithin’s father. He takes a keen interest in Swithin at the luncheon celebration that follows. In the evening he is taken to see the Tower.

XXVI. Viviette. is at the Tower, but hides when the Bishop’s party arrives. Swithin shows them the observatory, but the Bishop appears to be suspicious of something.

XXVII. Next day the Bishop accuses Swithin of having a woman in his room, and produces a bracelet as evidence. Swithin assures him he has done nothing wrong.

XXVIII. Louis gives the bracelet to Tabitha and urges Viviette to encourage the Bishop. He tries to sow suspicion in his sister’s mind against Swithin.

XXIX. Viviette and Tabitha divide their bracelets into two – which thwarts Louis in his suspicions. But he vows to set a trap for Viviette and Swithin.

XXX. Louis invites Swithin to dinner, then insists that he stay over. When Swithin disappears during the night, Louis interrogates Viviette, who admits that she loves Swithin – who had merely gone back to the Tower to take a reading.

XXXI. Viviette receives a proposal of marriage from the Bishop. Louis urges her to accept it, but she refuses. He leaves the house in a rage.

XXXII. Viviette and Swithin decide to reveal their marriage to the Bishop and to Louis. Viviette’s solicitor sends word that Sir Blount died much later than was previously thought. Viviette realises that her current marriage to Swithin is therefore invalid.

XXXIII. Viviette sends a letter of refusal to the Bishop. Swithin tells her not to worry about the legalities, and they plan to marry a second time.

XXXIV. Viviette reads a letter from Swithin’s solicitor regarding his unclaimed inheritance. She fears that she is preventing him from advancing in his best interests. Swithin urges that they undertake a second marriage.

XXXV. Her fears are confirmed when she reads the original inheritance letter from Swithin’s great-uncle, warning him against marriage. She decides to sacrifice her own happiness in Swithin’s best social interests. Finally she proposes postponing the marriage until he is twenty-five.

XXXVII. Swithin sets off for the southern hemisphere, and his lodgings at the Tower are dismantled. Viviette has a vision of a golden-haired child, and decides she must follow Swithin.

XXXVIII. She goes to Southampton but his ship has just left. She returns to Grandma Martin and writes letters to Swithin telling him that he cannot claim his inheritance.

XXXIX. Louis goes to Melchester and tells the Bishop that Viviette is ready to marry him. The Bishop arrives next day, and Viviette accepts him, believing that it will leave Swithin free to claim his inheritance.

XL. Swithin goes to America on the expedition to study the transit of Venus, and then settles on the South African cape. He receives a letter from his grandmother announcing Viviette’s marriage to the Bishop, and another from Viviette justifying her decision and giving him news of their child.

XLI. Three years later a newspaper announces the death of the Bishop. Swithin’s researches are complete, so he goes home. He meets Viviette on the Tower and is horrified to find her aged and unattractive. Nevertheless, he offers to marry her, but she dies from the shock.

Two on a Tower – characters

| Swithin St Cleve | a handsome young astronomer |

| Sir Bount Constantine | estate owner and African explorer |

| Lady Viviette Constantine | his attractive young wife |

| Louis Glanville | Viviette’s profligate brother |

| Dr Helmsdale | the Bishop of Melchester |

© Roy Johnson 2017

More on Thomas Hardy

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

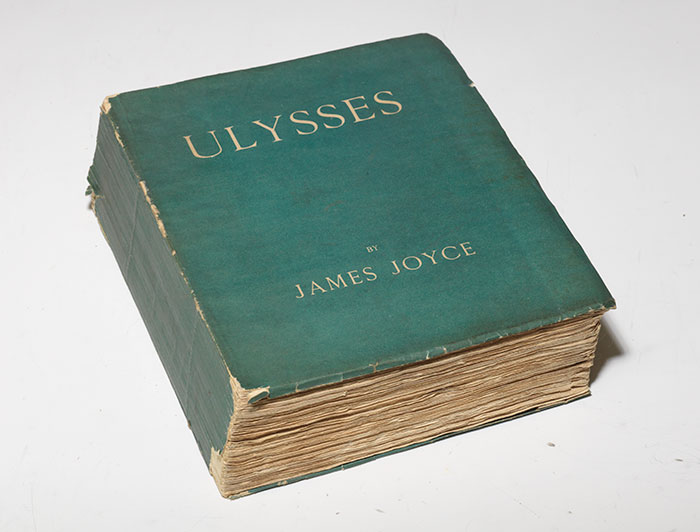

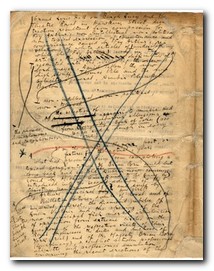

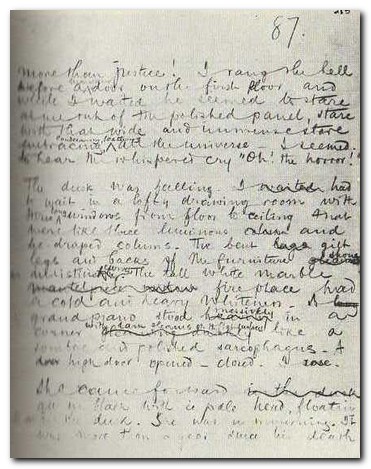

One factor which complicates the textual history of the novel is that Joyce continued working on it, even after it had been published. The printer in Dijon had made errors; Ezra Pound had made cuts and changes to the episodes in circulation via magazines, and Joyce revised multiple copies of his work which had been produced by non-professional typists from his near-illegible handwritten manuscripts.

One factor which complicates the textual history of the novel is that Joyce continued working on it, even after it had been published. The printer in Dijon had made errors; Ezra Pound had made cuts and changes to the episodes in circulation via magazines, and Joyce revised multiple copies of his work which had been produced by non-professional typists from his near-illegible handwritten manuscripts. The most spectacular of these attempts was that piloted by the German scholar Hans Walter Gabler, who proposed to ‘recover’ the original text by comparing surviving manuscripts, corrected proofs, and existing editions. He produced what was called a synoptic version, which was issued as Ulysses: The Corrected Text in 1986. This was designed to put an end to all uncertainties regarding the accuracy of the text.

The most spectacular of these attempts was that piloted by the German scholar Hans Walter Gabler, who proposed to ‘recover’ the original text by comparing surviving manuscripts, corrected proofs, and existing editions. He produced what was called a synoptic version, which was issued as Ulysses: The Corrected Text in 1986. This was designed to put an end to all uncertainties regarding the accuracy of the text.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

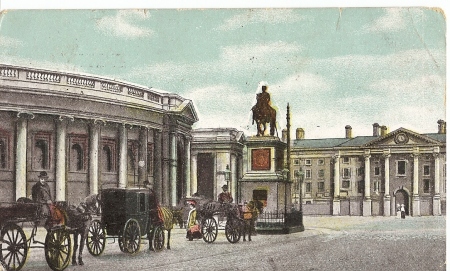

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad Nostromo

Nostromo The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent