1888. Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp was born into a socially prominent family in Wellington, New Zealand. Her father was a banker, who went on to become chairman of the Bank of New Zealand. She was first cousin of Elizabeth Beauchamp, who married into German aristocracy to become Countess Elizabeth von Arnim. She had a somewhat insecure childhood. Her mother left her when she was only one year old to go on a trip to England. She was raised largely by her grandmother, who features in some of the stories as ‘Mrs Fairfield’.

1888. Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp was born into a socially prominent family in Wellington, New Zealand. Her father was a banker, who went on to become chairman of the Bank of New Zealand. She was first cousin of Elizabeth Beauchamp, who married into German aristocracy to become Countess Elizabeth von Arnim. She had a somewhat insecure childhood. Her mother left her when she was only one year old to go on a trip to England. She was raised largely by her grandmother, who features in some of the stories as ‘Mrs Fairfield’.

1895. She attended Karori State School with her sisters, and proved to be gifted at writing, even though her spelling was poor.

1898. Attended Wellington Girls’ High School. Some of her earliest sketches appeared in the school magazine, and she won a composition prize for ‘A Sea Voyage’.

1901. She attended a private finishing school, showed a somewhat precocious interest in notions of ‘free love’, and continued writing stories. It is obvious even at this early stage that she was interested in creating a good prose style. The following was written when she was fifteen:

This evening I have sat in my chair with my reading lamp turned low, and given myself up to thoughts of the years that have passed. Like a strain of minor music they have surged across my heart, and the memory of them, sweet and fragrant as the perfume of my flowers, has sent a strange thrill of comfort through my tired brain.

1902. She becomes very passionate about writing and music, and is greatly influenced by Chekhov and Oscar Wilde, whose notoriety at that time was still at its height. She falls in love with Arnold Trowell, the son of her cello teacher.

1903. The family travel to London, and KM attends Queen’s College in Harley Street which had been founded by Charles Kingsley to prepare young women for higher education. On her first day there she meets Ida Baker, who was to become a central figure in the rest of her life. Five of her sketches appear in Queen’s College Magazine.

1906. She gives herself up to a rather bohemian lifestyle, and has affairs with both men and women. Because of this, her parents take her back home to New Zealand against her wishes.

1907. Three sketches and a poem published in the Melbourne Native Companion.

1907. Love affairs with two girls. Her family send her on a tour of New Zealand’s northern island. Love affair with a Maori girl.

1908. Her family give up in the fight against her rebellious nature, and she is allowed to go back to London with an allowance of £100 per year from her father. She lodges in Little Venice, and is in love with Garnet Trowell (Arnold’s twin brother).

1909. Pregnant by Garnet Trowell, she marries singing teacher George Bowden and leaves him the same evening (without consummating the marriage) to join a travelling light opera company in Glasgow. Her mother travels from New Zealand to restore order, and takes KM to Bavaria for what she describes as a ‘cold water cure’. She has a miscarriage.

1910. Returns to London, where she is hospitalised for gonorrhoea. She then goes back to live with her husband. Some of her stories are published in the New Age, alongside writers such as H.G. Wells, Arnold Bennett, and Hilare Belloc. At this stage she begins to suffer from severe bouts of illness.

1911. She has an abortion, then travels to Bruges and Geneva. In a German Pension published in the autumn.

1912. Meets John Middleton Murry and becomes with him the editor of a magazine which causes something of a scandal by its title alone – Rhythm. They live together, moving from England to France and back again, sometimes living together with her most devoted ex-lover, Ida Baker, who KM sometimes calls her ‘wife’.

1913. Friendships and fallings-out with both Henri and Sophia Gaudier-Brzeska, and Frieda and D.H.Lawrence. Last issue of Rhythm. Four stories published in the Blue Review, which then failed. Works as a film extra.

1914. Murry declared bankrupt: he leaves London to live in the country. KM ill: she writes love letters to fellow Rhythm contributor Francis Carco in France.

1915. Her brother Leslie Beauchamp visits her in London on his way to join regiment. KM leaves Murry and travels to Paris to live with Francis Carco. She is then reconciled with Murry, then goes back to Carco in France. Begins to write The Aloe (which becomes Prelude). Three stories published in Signature, which then folds. Brother killed in war. Moves to live in Bandol, France.

1916. Moves to Zennor, Cornwall with the Lawrences, who have violent rows and fights. Finally ‘leaves’ Murry. Visits Ottoline Morell’s home at Garsington, Oxfordshire.

1917. Moves to live in Chelsea, and begins to write ‘narratorless’ stories. Meetings with Virginia Woolf. Both of them realise that they are making similar experiments in prose fiction, and feel a combination of rivalry and friendship.

1918. Moves back to live in Bandol. Tuberculosis diagnosed. Returns to London and divorces George Bowden. Marries John Middleton Murry (wearing Frieda Lawrence’s wedding ring). They live together in a house in Hampstead – together with Ida Baker. Prelude published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press.

1919. Regular contact with Virginia Woolf. Writes reviews for the Athenaeum (edited by Murry). Moves to San Remo Italy with Ida Baker. Murry visits occasionally.

1920. Moves to live in Menton, France. Murry begins to dally with other women. KM returns to London. Bliss and Other Stories published by Constable. Returns to France.

1921. Returns to London to scare off Princess Bibesco, who has been dallying with Murry. Moves to live in Switzerland, where her neighbour Rainer Maria Rilke is writing the Duino Elegies. Intense creative bursts between bouts of severe illness.

1922. Moves to Paris for radium treatment for her TB. Moves back to Switzerland. Murry leaves KM, who prepares her will, making Murry her literary executor. Returns to France to join in the mystic ‘treatment’ which was then fashionable at the Gurdjieff Institute at Fontainbebleau, France.

1923. Murry arrives in Fontainebleau on the day that KM dies – 9 January 1923, aged just thirty-five.

Katherine Mansfield – web links

![]() Katherine Mansfield at Mantex

Katherine Mansfield at Mantex

Life and works, biography, a close reading, and critical essays

![]() Katherine Mansfield at Wikipedia

Katherine Mansfield at Wikipedia

Biography, legacy, works, biographies, films and adaptations

![]() Katherine Mansfield at Online Books

Katherine Mansfield at Online Books

Collections of her short stories available at a variety of online sources

![]() Not Under Forty

Not Under Forty

A charming collection of literary essays by Willa Cather, which includes a discussion of Katherine Mansfield.

![]() Katherine Mansfield at Gutenberg

Katherine Mansfield at Gutenberg

Free downloadable versions of her stories in a variety of digital formats

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, including Mansfield’s ‘Prelude’

![]() Katherine Mansfield’s Modernist Aesthetic

Katherine Mansfield’s Modernist Aesthetic

An academic essay by Annie Pfeifer at Yale University’s Modernism Lab

![]() The Katherine Mansfield Society

The Katherine Mansfield Society

Newsletter, events, essay prize, resources, yearbook

![]() Katherine Mansfield Birthplace

Katherine Mansfield Birthplace

Biography, birthplace, links to essays, exhibitions

![]() Katherine Mansfield Website

Katherine Mansfield Website

New biography, relationships, photographs, uncollected stories

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Katherine Mansfield

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on short stories

Between the Acts

Between the Acts The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

There were memorable and enduring works written during the conflict — Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire (1916) and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Edward Thomas. However, the majority of works which seem to encapsulate both the horrors of the war and the almost universal sense of disillusionment which followed were produced almost a decade later — Robert Graves Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway A Farewell to Arms (1929), Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929), Siegfried Sassoon Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), R.C. Sheriff Journey’s End (1929), Erich Maria Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

There were memorable and enduring works written during the conflict — Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire (1916) and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Edward Thomas. However, the majority of works which seem to encapsulate both the horrors of the war and the almost universal sense of disillusionment which followed were produced almost a decade later — Robert Graves Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway A Farewell to Arms (1929), Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929), Siegfried Sassoon Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), R.C. Sheriff Journey’s End (1929), Erich Maria Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

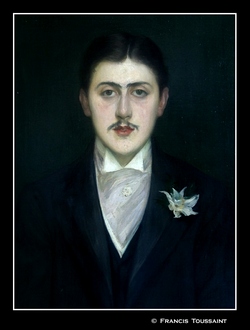

Most English-speaking readers will choose to read Marcel Proust in translation. And his literary style is quite demanding. His sentences are long, the paragraphs are huge, and his great novel is one of the longest ever – at a million and a half words. But the effort is worthwhile – and the benefits are enormous. Proust offers gems of psychological perception on every page, and his characters come alive in a way which makes you feel they become your personal friends. There is very little in the way of plot, suspense, or even story in a conventional sense. This modern classic is one which depicts an entire world of upper-class fin de siècle French characters circling round each other before and shortly after the First World War.

Most English-speaking readers will choose to read Marcel Proust in translation. And his literary style is quite demanding. His sentences are long, the paragraphs are huge, and his great novel is one of the longest ever – at a million and a half words. But the effort is worthwhile – and the benefits are enormous. Proust offers gems of psychological perception on every page, and his characters come alive in a way which makes you feel they become your personal friends. There is very little in the way of plot, suspense, or even story in a conventional sense. This modern classic is one which depicts an entire world of upper-class fin de siècle French characters circling round each other before and shortly after the First World War.

The second option

The second option The most recent

The most recent The Cambridge Companion to Proust

The Cambridge Companion to Proust