a novel in fragments

The Original of Laura (Dying is Fun) is a novel from beyond the grave by Vladimir Nabokov. Everyone has now woken up to the fact that Nabokov has been writing stories and novels about older men and younger women (and even younger girls) for quite some time. It’s no good taking his word for it (as he claims in his preface) that the original inspiration for Lolita came from a ‘painting’ by a chimpanzee in the Jardin des plantes. He had already written an entire novella (The Enchanter 1939) on exactly the same theme of what is now technically classed as paedophilia.

We now have his posthumous (and presumably last) work, which has been released even though he made an express wish that it should not be published if it were to be unfinished at the time of his death. And it certainly isn’t finished. Even to call it ‘a novel in fragments’ is stretching definitions somewhat. It consists of the drafts of three discernable and coherent chapters, plus lots of notes for other vaguely related materials which Nabokov was working on at the time of his death in 1977.

We now have his posthumous (and presumably last) work, which has been released even though he made an express wish that it should not be published if it were to be unfinished at the time of his death. And it certainly isn’t finished. Even to call it ‘a novel in fragments’ is stretching definitions somewhat. It consists of the drafts of three discernable and coherent chapters, plus lots of notes for other vaguely related materials which Nabokov was working on at the time of his death in 1977.

The novel-to-be seems to contain two main themes. The first is the sexual life of a flirty young girl called Flora (aged twelve in the semi-completed chapters) who is pursued lecherously by an ageing roué called (believe it or not) Hubert H. Hubert. She survives this and moves with her mother to an American college, where she studies French and Russian. Readers of Nabokov’s other novels will recognise elements from Laughter in the Dark, Lolita, and Pnin already.

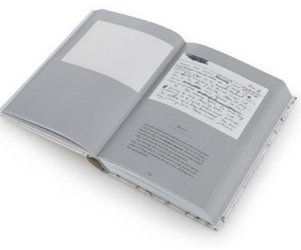

Part way through, the index cards on which Nabokov famously composed his novels change from relating a story to notes and instructions to himself – ideas for the plot, memos to invent a plausible name for a pharmaceutical, and lists of unusual words he was obviously striving to coin.

The second theme, which gives the book its sub-title, concerns Dr Philip Wild, a teacher at the college, whom Flora eventually marries. He is overweight, has bad feet, and he embarks on a quest of what he calls ‘dying by auto-dissolution’. It seems quite clear that the connections between these two parts of the narrative had not been conceptualised by Nabokov – which provides an interesting glimpse into his methods as a writer.

There are also hints that his story is the original source material for another book called My Laura written by somebody else that went on to become a best-seller. Here we have further echoes of Lolita, and typical Nabokovian playfulness – but since this theme remains undeveloped it warrants little attention.

This brings us to the book as a physical object and a product of print production. It’s the nearest a reader could get to seeing the system of writing for which Nabokov was famous. The index cards on which he wrote are photographically reproduced at the top of each right-hand page, with the text of the card reproduced below, complete with mis-spellings, grammatical errors, and slips of the pen.

The cover of the book is a photo-print of a typical index card, and each of the 138 index cards also has perforated edges, so theoretically they can be removed from the book and arranged in a different order if required. I imagine this gimmick will be dropped when the book is published in paperback, but Nabokovians and bibliophiles will undoubtedly want to possess this novelty edition.

That’s the good part. The not-so-good news is that the book is set in a font (Filosofia, by Zuzana Licko) which is a version of Bodoni. The body text is quite elegant and readable, but some headlines are set in the font’s unicase version, which has capitals and lower case of the same height. I am quite confident that Nabokov would have detested such affectation, and the results on some pages look awful.

The book has been created by Chip Kidd, a respected graphic designer, but I’m afraid this does not add anything to the appeal of this particular book or to Nabokov’s oeuvre as a whole. The index cards come out of this well enough, but reading the text in black print on dark grey paper is no joke.

The story is presented in an interesting and very allusive manner. There are unexplained shifts in the temporal sequence of events and the narrative point of view. These suggest that Nabokov was still experimenting with narrative strategies right up to the end of his life. [I have examined this phenomenon in my study of his short stories.] However, it has to be said that in common with the prose style of his other late works, it is contaminated by lots of irritating quirks and tics, such as his weakness for alliteration – though it might be slightly unfair to judge him from what was obviously a work in progress.

‘foetally folded … narrow nates … He brought from the favourite florist of fashionable girls a banal bevy of bird of paradise flowers’

It has been claimed that Nabokov would envisage a novel complete in his mind before starting to write it. This was supposed to allow him to work on any section his wished, then place a card in the stack already written. The cards in this volume cast severe doubts on that claim. There is some sense of fluency in the semi-completed chapters, but it’s of a kind that characterises his less distinguished novels; and the remainder prove that he was thinking aloud and making it up as he went along.

The volume has a preface written by his son Dmitri which is a pompous and badly-written piece of self-indulgence that tells us very little about the manuscript and why it came to be published. What it does tell us is how not to behave as the offspring of a famous person.

So, it’s a production with a number of interesting features. It’s clearly a piece of gross commercial opportunism; it gives more ammunition to those who see Nabokov as a great writer with a dubious interest in under-age girls; it’s unlikely to enhance his reputation as a writer; but for me it’s a fascinating glimpse into the writer’s workshop – and further proof that we shouldn’t take what writers say about their own motivations and methods at face value.

© Roy Johnson 2010

Vladimir Nabokov, The Original of Laura: (Dying is Fun) a novel in fragments, London: Penguin, 2009, pp. 278, ISBN 0141191155

More on Vladimir Nabokov

More on literary studies

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories

The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All essays are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All essays are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel – the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian father. She has a handsome young suitor – but her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant town house. Who wins out in the end? You will be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, with a sensitive picture of a woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel – the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian father. She has a handsome young suitor – but her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant town house. Who wins out in the end? You will be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, with a sensitive picture of a woman’s life.  The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

With her large legacy, Isabel travels the Continent and meets an American expatriate, Gilbert Osmond, in Florence. Although Isabel had previously rejected both Warburton and Goodwood, she accepts Osmond’s proposal of marriage. She is unaware that this marriage has been actively promoted by the accomplished but untrustworthy Madame Merle, another American expatriate, whom Isabel had met at the Touchetts’ estate.

With her large legacy, Isabel travels the Continent and meets an American expatriate, Gilbert Osmond, in Florence. Although Isabel had previously rejected both Warburton and Goodwood, she accepts Osmond’s proposal of marriage. She is unaware that this marriage has been actively promoted by the accomplished but untrustworthy Madame Merle, another American expatriate, whom Isabel had met at the Touchetts’ estate. The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

Five months later he joins Anna at Givré, her country chateau where they meet to plan their future. Anna wants to help her stepson Owen, who wants to marry someone who does not meet with the approval of his grandmother, the dowager Marquise de Chantelle. Darrow plans to marry Anna and take her on his next diplomatic assignment to South America. However, it turns out that Anna has hired a governess for her daughter Effie — none other than Sophy Viner. Darrow feels acutely embarrassed by the situation, and Sophy pleads with him not to say anything that will threaten her employment.

Five months later he joins Anna at Givré, her country chateau where they meet to plan their future. Anna wants to help her stepson Owen, who wants to marry someone who does not meet with the approval of his grandmother, the dowager Marquise de Chantelle. Darrow plans to marry Anna and take her on his next diplomatic assignment to South America. However, it turns out that Anna has hired a governess for her daughter Effie — none other than Sophy Viner. Darrow feels acutely embarrassed by the situation, and Sophy pleads with him not to say anything that will threaten her employment.

The Age of Innocence

The Age of Innocence The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales