tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

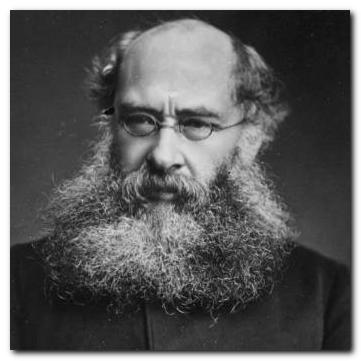

The Warden was first published in 1855 by Longman. It was Trollope’s fourth novel, but the first in the series which became known as The Barsetshire Chronicles, and it established his reputation as a popular novelist. The others in the sequence are Barchester Towers, Doctor Thorne, Framley Parsonage, The Small House at Allington, and The Last Chronicle of Barset.

The opening of the novel makes it clear that Barchester was supposed to be a cathedral town in the south west of England, and it is probably constructed imaginatively from elements of Salisbury and Wells cathedrals, which Trollope knew well from his travels around the south west in his professional capacity as inspector of the postal system. (He is credited with having invented the post box.)

The Warden – critical commentary

The strengths

Undoubtedly the main strength of this novel is the characterisation of the Reverend Harding – the gentle, considerate widower who looks after his charges in the hospital with loving care; who has a passion for music and has published a book on the subject at his own expense; and who plays the cello imaginatively when in an emotionally charged state. He also has a finely developed conscience, which does not let him continue in a sinecure that provides him with a generous living for little effort and few responsibilities.

Both friends and enemies alike urge him to stay where he is, but he cannot live with the thought that the money which provides his generous income might rightly belong to the twelve paupers whose care is his raison d’etre as warden.

Contemporary and modern readers alike can be forgiven for thinking that some last-minute reprieve will solve his dilemma – and it is to Trollope’s credit that no such melodramatic solution comes about. Harding moves out of his comfortable home with his unmarried daughter; he sells furniture; he goes to live in rented accommodation; and he ends up in a much smaller parish on a reduced income.

The reader therefore is left with no uplifting conclusion to the novel – except that Reverend Harding has acted according to his conscience and paid the material price of doing so. This plot construction is admirably restrained, and the best feature of the novel.

The weaknesses

But there are a number of weaknesses. The most important is thematic; the lesser weaknesses are technical – to do with the art and craft of novel-writing. The main problem arises from the fact that the trigger for the entire drama is political and financial malpractice in the established church. This corruption ranges from simony (the selling of church preferments and benefices) to nepotism (favouritism to relatives in making appointments).

As a major landowner the church had (and still has) vast reservoirs of wealth which it used to pay its clergy, all of which the novel makes fairly clear. And some of the positions they held are largely sinecures. Indeed, part of the warden’s moral dilemma is not just that he is receiving a large annual salary to which he might not be legally entitled, but that he receives this salary for doing next to nothing.

But the study of this moral problem remains at a purely personal level. The warden’s distressed state of mind is traced minutely by Trollope, but no attempt is made to explore the larger issues of ecclesiastical politics, finances, and corruption – even though famous legal cases are mentioned in the narrative.

We do not even know if Reverend Harding’s salary is a legitimate outcome of Hiram’s will or not – because even the Queen’s Council does not come to any conclusion on the matter. The most important legal and financial issue underpinning the story is simply left unexamined.

It is as if Trollope can only see as far as ‘characters’ – the tender hearted warden and the arrogant archdeacon – and is not interested in probing the causes of the social problems that make up his story. Neither is the chain of responsibility for the administration of the will examined, and the roles of the bishop, archdeacon, warden, and steward are all left at the level of friendships and family connections.

Technical weaknesses

There are two problems to which many critics have found objection on the grounds of disrupting the tone and the manner of the novel. The first of these is the introduction of huge digressions when Trollope suddenly launches a chapter-long satirical attack on the Jupiter newspaper – which everybody above the age of fifteen would have known full well to be his fictionalised version of The Times.

The characters and their interaction with each other are suddenly put on hold whilst Trollope criticises the newspaper for its dominance, its undue influence in society, and its lack of accountability (a criticism which he does not think to apply to the church).

These are fairly reasonable views to hold against the press – but Trollope almost abandons his responsibility to construct a coherent novel in his eagerness to berate (at great length) the organ which is bringing questionable practices within the church to the public’s attention.

This is followed by two further digressions with similar purposes – the parodies of Carlyle and Dickens. His accounts of Dr Pessimist Anticant [Thomas Carlyle] and Mr Popular Sentiment [Charles Dickens] become like two obtrusive satirical essays inserted into the delicate fabric of the novel.

It is not Trollope’s opinion of Carlyle and Dickens one objects to, but the fact that no attempt has been made to integrate these episodes with the remainder of the novel. They are materials of a different kind to the lives of the Reverend Harding, his daughters, and his domestic life. As Henry James observes in his essay on Trollope (in Partial Portraits) ‘both these little jeux d’esprit are as infelicitous as they are misplaced’.

This technical flaw is both signalled and reinforced by Trollope’s weakness with names. It is simply not possible to construct a credible fictional world in the realist tradition, containing railways, cathedrals, and named London streets, then populate it with characters called Sir Abraham Haphazard, Dr Pessimist Anticant, Mr Popular Sentiment, and Reverend Quiverful. These belong possibly in an eighteenth century work, but they cannot sit persuasively alongside characters called Eleanor Harding and Mr Chadwick.

The Warden – study resources

The Warden – OUP paperback – Amazon UK

The Warden – OUP paperback – Amazon US

The Warden – All six of the Barsetshire novels – £0.50

The Warden – All the Barsetshire novels – Amazon UK

The Warden – Project Gutenberg eBooks [FREE]

The Warden – Audiobook – FREE at LibriVox

Anthony Trollope – A website with plots summaries, TV and Radio links, quotes, quizzes, seminar groups, competitions – official site of the Trollope Society.

The Warden – plot summary

Chapter 1. The Reverend Septimus Harding is a modest clergyman in the cathedral town of Barchester in the south west of England. He is in charge of an almshouse for twelve old workmen, and he supplements their meagre weekly allowance from his own stipend. Rumours begin to circulate that his own generous income should be divided amongst his charges, according to the terms of Hiram the founder’s will.

Chapter 2. John Bold has inherited property, and although technically a surgeon, he practises medicine amongst the poor without charging for his services. He is a radical reformer and is in love with Harding’s daughter Eleanor. Harding’s son-in-law Archdeacon Grantly disapproves of Bold, who starts legal enquiries into the financial basis of the almshouses (the hospital).

Chapter 3. Bold asks Harding to discuss the terms of Hiram’s will. Harding pleads ignorance, but is upset by the fear that he might be in the wrong in accepting a salary which ought to be distributed amongst more needy recipients. Harding consults the bishop, who refers him to his son the strict archdeacon. Harding also reveals the discomfiture he feels in his position because Bold is linked romantically to his daughter Eleanor.

Chapter 4. The twelve occupants of the hospital are divided over the issue of what they are led to believe is their rightful inheritance of one hundred pounds a year for each man. But eventually nine of them put their names to a petition, defying their ‘leader’ Bunce, who is against the action.

Chapter 5. The archdeacon visits the hospital and lectures the men, criticising them for their petition. He seeks legal advice from a Queen’s Counsel, Sir Abraham Haphazard. The warden is deeply embarrassed by the public dispute and the threat to his good reputation.

Chapter 6. Bold’s sister Mary tries to persuade him to give up the case for the sake of their friendship with the Harding family – but he is resistant. Mary attends a party at the warden’s home, following which Eleanor exchanges views with both her father and with Bold.

Chapter 7. The scandal becomes more widely known and is taken up by the national daily newspaper the Jupiter [The Times] which elevates it to a conflict between Church and State, and between Protestant and Catholic politics.

Chapter 8. The archdeacon lives very comfortably but his practical wife disagrees with his position regarding the scandal – largely because it impedes Eleanor’s chances of securing Bold as a husband. She also thinks it causes unnecessary worry to her father. Chadwick arrives with an opinion from Sir Abraham Haphazard – that there are weaknesses in the legal documents which the archdeacon assumes to be favourable to his case.

Chapter 9. In private conference the archdeacon reveals Sir Haphazard’s opinion to the bishop and the warden, claiming that they have nothing to fear, but insisting that the opinion is kept secret. The warden is deeply troubled by the lack of clarity on the matter, even though the legal opinion clears him of any blame. He thinks of resigning from his position as a solution to the dilemma, but the archdeacon bullies him in the name of the larger good of the Church.

Chapter 10. The warden is completely crestfallen and sees his reputation and his way of life in ruins. He eventually confides in his daughter Eleanor, who comforts him and encourages him to give everything up and live in an untroubled state of simplicity.

Chapter 11. Eleanor decides to rescue her father’s feelings by appealing to John Bold to call off his inquiries. When she does so, Bold pours out his heart and his love for her. There is an implication that these avowals constitute an engagement. He agrees to leave the case alone, even though others might continue to pursue it.

Chapter 12. Bold visits the archdeacon to inform him of his intention to abandon the case. Dr Grantly receives the news with lofty disdain and insults Bold, refusing to believe that he is acting in good faith.

Chapter 13. When Eleanor goes to tell her father that Bold is calling off the action, it is too late. Another editorial in the Jupiter names the warden specifically in the scandal. Harding decides to go to London to confront Haphazard. He also has plans to retire to another parish.

Chapter 14. Bold arrives in London to see Tom Towers, journalist for the Jupiter. A whole chapter is devoted to a satirical critique of the newspaper and the unaccountable power it holds in forming and manipulating public opinion.

Chapter 15. When Bold confronts Towers he finds that the case has been taken up by Dr Pessimist Anticant [Thomas Carlyle] and Mr Popular Sentiment [Charles Dickens]. Towers flatly refuses to use any influence on the paper on the spurious grounds of impartiality and public interest. Bold buys a copy of the serial novel The Almshouse [which is a benign parody of Dickens].

Chapter 16. Rev Harding also goes to London – to see Haphazard and escape from the archdeacon. When he is kept waiting for an appointment he hides in Westminster Abbey, wrestling with his conscience. He then passes time in a supper-house and a coffee shop.

Chapter 17. Sir Abraham Haphazard, the attorney general, tells Harding that Bold has withdrawn his legal action and advises him to forget the issue and continue in his present position. He is unable to explain the exact terms of Hiram’s will. But Harding insists that it is a matter of conscience, and feels that he has no option but to resign from his position as warden.

Chapter 18. When the warden arrives back at his hotel, the archdeacon argues that it would be madness to resign his position – using largely financial arguments. But Rev Harding sticks to his position to resign, even though he will lose his income.

Chapter 19. The next morning, despite entreaties from his daughter to delay the decision, the warden writes two letters of resignation to the bishop then returns home. The archdeacon visits his lawyers, who propose the solution of an exchange arrangement with another parish.

Chapter 20. The bishop accepts Harding’s resignation but offers him money and accommodation in order to help him survive. But Harding refuses both offers – as he does the idea of an ecclesiastic exchange. He bids a sad farewell to the bedesmen in the hospital.

Conclusion. Harding moves into lodgings and eventually becomes preceptor in a small Barchester parish. living in reduced circumstances. Eleanor marries Bold, who gradually becomes friendly with the archdeacon.

The Warden – principal characters

| Reverend Septimus Harding | the warden of the hospital for elderly paupers at Barchester |

| Susan Harding | his elder daughter, married to the archdeacon |

| Eleanor Harding | his younger daughter, in love with John Bold |

| Dr Theophilius Grantly | the conservative archdeacon, son of the bishop, and the warden’s son-in-law |

| John Bold | a non-practising surgeon and radical reformer |

| Mary Bold | his sister and friend to Eleanor Harding |

| Chadwick | the steward of Hiram’s will |

| Finney | Bold’s lawyer |

| Mr Bunce | the aged ‘sub-warden’ at the hospital |

| Sir Abraham Haphazard | a London barrister QC |

| Tom Towers | a journalist and editor of The Jupiter |

The Warden – further reading

![]() Ruth apRoberts, Trollope, Artist and Moralist, London: Chatto and Windus, 1971.

Ruth apRoberts, Trollope, Artist and Moralist, London: Chatto and Windus, 1971.

![]() Victoria Glendenning, Trollope, London: Pimlico, 2002.

Victoria Glendenning, Trollope, London: Pimlico, 2002.

![]() Henry James, Partial Portraits, 1888.

Henry James, Partial Portraits, 1888.

![]() James R. Kincaid, The Novels of Anthony Trollope, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

James R. Kincaid, The Novels of Anthony Trollope, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

![]() Ellen Moody, Trollope on the Net, London: Hambledon Continuum, 1999.

Ellen Moody, Trollope on the Net, London: Hambledon Continuum, 1999.

![]() Richard Mullen, Anthony Trollope: A Victorian in his World, London: Duckworth, 1990.

Richard Mullen, Anthony Trollope: A Victorian in his World, London: Duckworth, 1990.

![]() Bill Overton, The Unofficial Trollope, Lanham Rowman & Littlefield (MD), 1982.

Bill Overton, The Unofficial Trollope, Lanham Rowman & Littlefield (MD), 1982.

![]() Donald Smalley, Trollope: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 2013.

Donald Smalley, Trollope: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 2013.

![]() John Sutherland, Victorian Fiction: Writers, Publishers, and Readers, London: Palgrave, 2006.

John Sutherland, Victorian Fiction: Writers, Publishers, and Readers, London: Palgrave, 2006.

![]() Anthony Trollope, An Autobiography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Anthony Trollope, An Autobiography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

![]() Stephen Wall, Trollope and Character, London: Faber and Faber, 1988.

Stephen Wall, Trollope and Character, London: Faber and Faber, 1988.

© Roy Johnson 2014

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

With Kate as a companion, Milly goes to see an eminent physician, Sir Luke Strett, because she’s afraid that she is suffering from an incurable disease. The doctor is noncommittal but Milly fears the worst. Kate suspects that Milly is deathly ill. After the trip to America where he had met Milly, Densher returns to find the heiress in London. Kate wants Densher to pay as much attention as possible to Milly, though at first he doesn’t quite know why. Kate has been careful to conceal from Milly (and everybody else) that she and Densher are engaged.

With Kate as a companion, Milly goes to see an eminent physician, Sir Luke Strett, because she’s afraid that she is suffering from an incurable disease. The doctor is noncommittal but Milly fears the worst. Kate suspects that Milly is deathly ill. After the trip to America where he had met Milly, Densher returns to find the heiress in London. Kate wants Densher to pay as much attention as possible to Milly, though at first he doesn’t quite know why. Kate has been careful to conceal from Milly (and everybody else) that she and Densher are engaged.

The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

Chapter VIII. Grace visits Mrs Charmond in her gloomily placed house and makes a very good impression. Mrs Charmond invites her to be a traveling companion on her planned European tour. Meanwhile, Giles plants fir trees with Marty South.

Chapter VIII. Grace visits Mrs Charmond in her gloomily placed house and makes a very good impression. Mrs Charmond invites her to be a traveling companion on her planned European tour. Meanwhile, Giles plants fir trees with Marty South.

To the Lighthouse

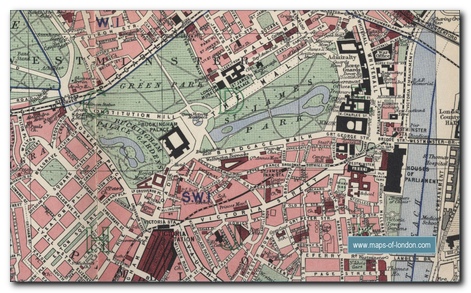

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf Under the Greenwood Tree

Under the Greenwood Tree Far from the Madding Crowd

Far from the Madding Crowd The Return of the Native

The Return of the Native The Mayor of Casterbridge

The Mayor of Casterbridge

Tess: DVD

Tess: DVD Jude the Obscure

Jude the Obscure The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories