tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

Madame de Treymes was published in 1907. It was Edith Wharton’s first major work after the success of The House of Mirth which had been published two years previously. The tale features American expatriates living in France, and contrasts new world simplicity and individual freedoms with old world family traditions and manipulation.

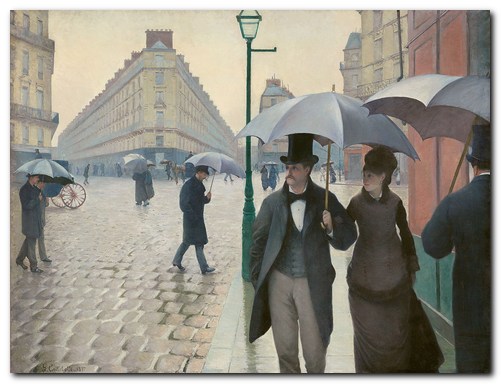

Paris: Rainy Street – Gustave Caillebotte 1848-1894

Madame de Treymes – critical commentary

This is a story straight out the mould of Henry James – with hints of Balzac. Democratically open but young and maybe naive American honesty is pitted again tradition-bound European guile with its money-centric and snobbish exclusivity hiding behind a hypocritical veil of religious values. The situation also has a slightly Gothic tinge: an unhappy young woman, trapped in a loveless marriage to a corrupt husband, with very little chance of escape, is hounded by ruthlessly devious relatives.

The central conundrum with which one is left at the end of the tale is Madame de Treymes’ possible motive(s) for deceiving Durham? She understands and explains the family’s traditional and tightly controlled attitudes (fuelled by religious belief) towards divorce. This would be entirely in keeping with social conventions at the time, when the Catholic church frowned upon divorce with a force which was a de facto prohibition.

But this apparently religious objection to divorce has a much more material basis in French society, which was governed by the Napoleonic Code that kept inherited wealth and property concentrated into family units rather than freely distributed amongst individuals. This explains the reason why the Malrive family wish to trade Fanny’s son in return for the divorce. She can exercise her rights to a divorce under civil law, but they keep the son, theoretically united with his father, and thereby prevent any wealth passing out of the family.

The other possible source of her ambiguous motivation is that she is attracted to Durham. After all, she is unhappily married herself (like Fanny) although she does have a lover. But she keeps Durham guessing in a rather flirtatious manner. There is also the fact that Durham certainly spends far more time in the story discussing matters with Madame de Treymes than he does with his purported love object, Fanny de Malrive. But there is no substantial evidence in the text to support this notion, and the potential romantic connection between the two of them is not developed in any way.

Novella?

This is a long story – which leads a number of commentators to consider it as a novella. Edith Wharton was certainly attracted to and proficient in the novella as a literary genre, as her early work The Touchstone (1900) and more famous Ethan Frome (1911) demonstrate.

And the clash between American individualism and French family tradition is certainly a unifying factor amongst the various elements of the story. But there are too many loose ends and unresolved issues in the narrative to qualify it as a novella.

Monsieur de Malrive’s misdeeds are left unexamined, as are those of Monsieur de Treymes. Durham’s attempts to help Madame de Malrive presumably come to nothing (because of the stranglehold the Malrive family has over the conflict) and the potential relationship between Durham and Madame de Treymes fizzles out with everyone going their own way. There is simply not a sufficiently powerful enough resolution to events. It is a reasonably successful story, but it lacks the compression of theme, structure, events, and place which is common to successful novellas.

Madame de Treymes – study resources

![]() The Works of Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Works of Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

![]() The Works of Edith Wharton – Amazon US

The Works of Edith Wharton – Amazon US

![]() Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

![]() Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon US

Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon US

![]() The Descent of Man and Other Stories – Project Gutenberg

The Descent of Man and Other Stories – Project Gutenberg

![]() A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

Madame de Treymes – plot summary

Part I. In Paris, American bachelor John Durham pays court to unhappily married Fanny de Malrive, his friend from childhood. She expresses a great enthusiasm for the simplicity and openness of her native America, as distinct from the constricted and rule-bound society into which she has married. But she lives in France for the sake of being near her son.

Part II. She argues that French society and her husband threaten to corrupt the boy. Durham offers to marry her after she has been divorced. She thinks her husband’s family will not agree to a divorce, but that her sister-in-law Madame de Treymes might help.

Part III. Durham has been a childhood friend of Fanny, but meeting her again in France he finds her much more sophisticated. Visiting her a few days later with his mother and sisters, he first meets Madame de Treymes, who he also finds fascinating.

Part IV. Durham applies to his cousin Mrs Boykin for information about the mysterious Madame de Treymes. But she and her husband are comically xenophobic, and very critical of Madame de Treymes, whose lover is a Prince with gambling debts.

Part V. By giving money at a charity event, Durham is invited to the Hotel de Malrive, the austere family home of Fanny’s in-laws. There he realises the stifling forces of cold and hostile tradition he will be up against. However, Madame de Treymes is sympathetic to his case and agrees to dine with him.

Part VI. At Durham’s suggestion, the Boykins are suddenly flattered to invite a French aristocrat to dinner. Madame de Treymes tells Durham that the family will not consent to a divorce, and reveals that she has borrowed family money which she cannot repay. Durham believes that this to repay her lover’s gambling debts, and she is offering to trade her influence in exchange for his money. He refuses her offer.

Part VII. Durham accepts the defeat of his hopes, but then suddenly Madame de Treymes arrives with the news that the Marquis de Malrive has decided not to oppose the divorce. She claims it was Durham’s honourable and sensitive approach which has changed things. Durham is slightly sceptical.

Part VIII. Durham goes to Italy, but returns to the news that a money scandal has engulfed Prince d’Armillac, the lover of Madame de Treymes. Durham tries to thank and repay Madame de Treymes for the good services she has rendered him, but she claims that she has already been repaid – without saying in what form.

Part IX. Durham goes to England with his mother and sisters whilst the legal process of divorce takes its course. However, on a business trip back to Paris he meets Madame de Treymes at the Hotel de Malrive. She explains her admiration for his having refused to gain Fanny by paying for influence with the family. She also reveals that it was not her influence which changed the family’s attitude to the divorce.

Part X. She confesses that the family want to claim Fanny’s son which they can do under French law, which puts the family first, before individuals. Her earlier offer of assistance was a deceit, because the decision had already been taken. Durham realises that even telling Fanny all this will destroy his chances of marrying her. But then Madame de Treymes takes pity on Durham and his plight and reveals that even her last argument about possession of the boy was a deceit as well. Durham leaves to tell Fanny the whole story, knowing his chances of marrying her are gone.

Madame de Treymes – Principal characters

| John Durham | an American in France (40) |

| Marquise Fanny de Malrive | his childhood friend, neé Fanny Frisbee |

| Madame Christiane de Treymes | Fanny’s sister-in-law |

| Mrs Bessie Boykin | Durham’s cousin |

| Elmer Boykin | her husband |

| Prince d’Armillac | Madame de Treymes’ lover, a gambler |

Edith Wharton’s 42-room house – The Mount

Further reading

Louis Auchincloss, Edith Wharton: A Woman of her Time, New York: Viking, 1971,

Elizabeth Ammons, Edith Wharton’s Argument with America, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1982, pp.222. ISBN: 0820305138

Janet Beer, Edith Wharton (Writers & Their Work), New York: Northcote House, 2001, pp.99, ISBN: 0746308981

Millicent Bell (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Edith Wharton, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp.232, ISBN: 0521485134

Alfred Bendixen and Annette Zilversmit (eds), Edith Wharton: New Critical Essays, New York: Garland, 1992, pp.329, ISBN: 0824078489

Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN: 0810927950

Gloria C. Erlich, The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton, California: University of California Press, 1992, pp.223, ISBN: 0520075838

Susan Goodman, Edith Wharton’s Women: Friends and Rivals, UPNE, 1990, pp.220, ISBN: 0874515246

Irving Howe, (ed), Edith Wharton: A collection of Critical Essays, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1986,

Jennie A. Kassanoff, Edith Wharton and the Politics of Race, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp.240, ISBN: 0521830893

Hermione Lee, Edith Wharton, London: Vintage, new edition 2008, pp.864, ISBN: 0099763516

R.W.B. Lewis, Edith Wharton: A Biography, New York: Harper and Rowe, 1975, pp.592, ISBN: 0880640200

James W. Tuttleton (ed), Edith Wharton: The Contemporary Reviews, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.586, ISBN: 0521383196

Candace Waid, Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991,

Sarah Bird Wright, Edith Wharton A to Z: The Essential Reference to Her Life and Work, Fact on File, 1998, pp.352, ISBN: 0816034818

Cynthia Griffin Wolff, A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton, New York: Perseus Books, second edition 1994, pp.512, ISBN: 0201409186

Other works by Edith Wharton

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Edith Wharton – web links

Edith Wharton at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, tutorials on the shorter fiction, bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

Edith Wharton at Gutenberg

Free eTexts of the major novels and collections of stories in a variety of digital formats – also includes travel writing and interior design.

Edith Wharton at Wikipedia

Full details of novels, stories, and travel writing, adaptations for television and the cinema, plus web links to related sites.

The Edith Wharton Society

Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University.

The Mount: Edith Wharton’s Home

Aggressively commercial site devoted to exploiting The Mount – the house and estate designed by Edith Wharton. Plan your wedding reception here.

Edith Wharton at Fantastic Fiction

A compilation which purports to be a complete bibliography, arranged as novels, collections, non-fiction, anthologies, short stories, letters, and commentaries – but is largely links to book-selling sites, which however contain some hidden gems.

Edith Wharton’s manuscripts

Archive of Wharton holdings at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Edith Wharton

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

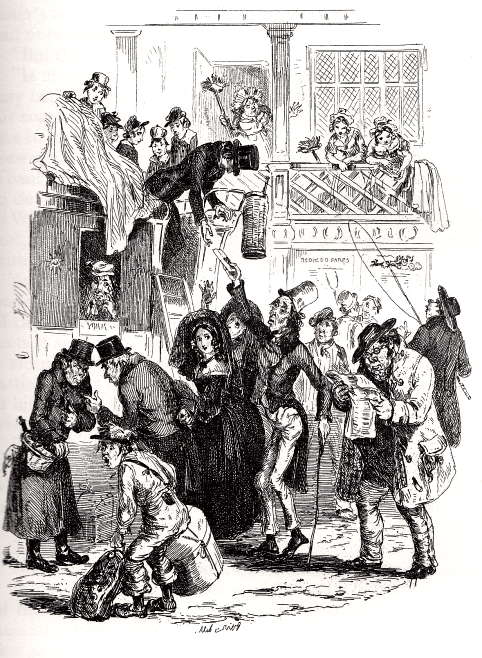

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

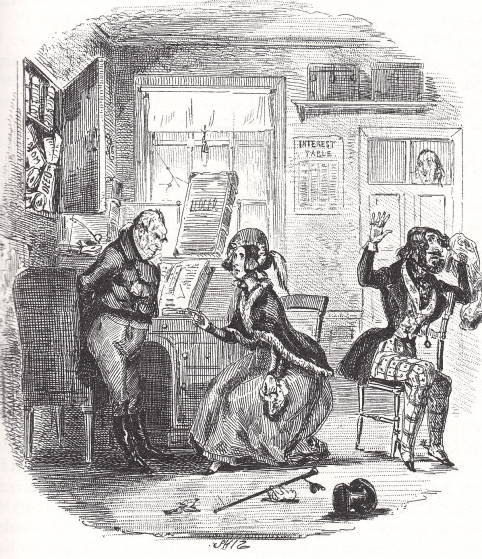

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.