tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

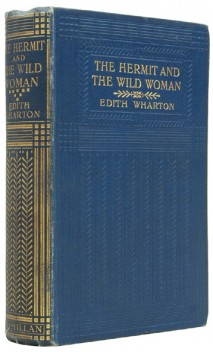

The Reckoning first appeared in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, New York, 1902. The story was subsequently included in Edith Wharton’s collection of short fiction, The Descent of Man and Other Stories published by Charles Scribner’s in 1904. It is one of the many stories she wrote which featured the ‘new ethics’ emerging from the relaxation of the divorce laws in the United States.

The Reckoning- critical commentary

This is an amazingly mature work for the relatively young Edith Wharton, and proof positive that she was thinking critically about the issues of personal liberty within marriage, the grounds for divorce, and the possible consequences of sexual liberty, long before her own affair with Morton Fullerton in 1908 and her eventual divorce from her husband Teddy Wharton in 1912.

In tone, subject, and style the story represents a transition between the nineteenth and the twentieth century tradition of short stories. It has the understated world weariness of Maupassant and Chekhov, and the incisive, critical realism which was to come in the same decade from James Joyce and Virginia Woolf.

Stucture

The story is very elegantly structured in three well balanced sections. The first introduces the Westall’s, their pact of individual liberty within marriage, and Julia’s first doubts when she sees her husband’s interest in a younger woman.

The second section provides a flashback to Julia’s first marriage to John Armant, in which she felt trapped by a relationship that to her had become stale. This explains the origins of her agreement with Clement that an individual must have the right to move on when the time comes. But now in the present, after ten years marriage to Clement, she feels threatened by the very agreement she has helped to generate between them.

The third section represents the lessons she learns. Feeling sure that Clement is leaving her for Una Van Sidern, she returns to her former home and realises that when she left her former husband John Arment, she took no account of his feelings at the time. He confirms that he was an unwilling participant in the divorce – but he forgives her in retrospect.

The Reckoning – study resources

![]() The New York Stories – New York Review Books – Amazon UK

The New York Stories – New York Review Books – Amazon UK

![]() The New York Stories – New York Review Books – Amazon US

The New York Stories – New York Review Books – Amazon US

![]() Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

![]() Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon US

Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon US

![]() The Descent of Man and Other Stories – Project Gutenberg

The Descent of Man and Other Stories – Project Gutenberg

![]() A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Reckoning – story synopsis

Part I. Clement Westall has been speaking on radical proposals for personal freedom within marriage to a gathering of New York socialites at the Saturday salon of the Van Siderns. His wife Julia previously shared his views but now feels uneasy about their being made known in public – especially when they are enthusiastically embraced by the twenty-six year old Una Van Sidern, to whom her husband admits being attracted.

Part II. Julia felt trapped in her first marriage to John Armant, and she married Clement Westall on the understanding that individuals should be free to move on by mutual consent when they felt the marriage had served its useful purpose. But after ten years of marriage to Westall she has come to believe that these ideas no longer apply in her own case. So when he plans to go ahead with another speech at the Van Siderns she asks him not to go. He asserts their old agreement to move on when they wish to form a new relationship.

Part III. When he leaves to join the Van Siderns she feels her whole world collapse, as if she had been caught out by a new rule of her own making. She wanders about New York all day, uncertain what to do with her tumultuous emotions. Finally she ends up at her old home where her first husband still lives. She explains to him that Clement Westall is about to leave her for a younger woman, which has forced her to realise that when one person wishes to leave a marriage, the other may not, and may not understand the need for separation. She realises that this might have been the situation when she divorced John Armant, which he confirms to have been the case. She asks his forgiveness – which he grants her.

Principal characters

| Clement Westall | a New York lawyer and socialite |

| Julia Westall | his wife |

| John Armant | Julia’s first husband |

| Una Van Sidern | a 26 year old socialite |

Edith Wharton’s 42-room house – The Mount

Further reading

Louis Auchincloss, Edith Wharton: A Woman of her Time, New York: Viking, 1971,

Elizabeth Ammons, Edith Wharton’s Argument with America, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1982, pp.222. ISBN: 0820305138

Janet Beer, Edith Wharton (Writers & Their Work), New York: Northcote House, 2001, pp.99, ISBN: 0746308981

Millicent Bell (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Edith Wharton, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp.232, ISBN: 0521485134

Alfred Bendixen and Annette Zilversmit (eds), Edith Wharton: New Critical Essays, New York: Garland, 1992, pp.329, ISBN: 0824078489

Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN: 0810927950

Gloria C. Erlich, The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton, California: University of California Press, 1992, pp.223, ISBN: 0520075838

Susan Goodman, Edith Wharton’s Women: Friends and Rivals, UPNE, 1990, pp.220, ISBN: 0874515246

Irving Howe, (ed), Edith Wharton: A collection of Critical Essays, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1986,

Jennie A. Kassanoff, Edith Wharton and the Politics of Race, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp.240, ISBN: 0521830893

Hermione Lee, Edith Wharton, London: Vintage, new edition 2008, pp.864, ISBN: 0099763516

R.W.B. Lewis, Edith Wharton: A Biography, New York: Harper and Rowe, 1975, pp.592, ISBN: 0880640200

James W. Tuttleton (ed), Edith Wharton: The Contemporary Reviews, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.586, ISBN: 0521383196

Candace Waid, Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991,

Sarah Bird Wright, Edith Wharton A to Z: The Essential Reference to Her Life and Work, Fact on File, 1998, pp.352, ISBN: 0816034818

Cynthia Griffin Wolff, A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton, New York: Perseus Books, second edition 1994, pp.512, ISBN: 0201409186

Edith Wharton’s writing

Other works by Edith Wharton

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Edith Wharton – web links

Edith Wharton at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, tutorials on the shorter fiction, bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

The Short Stories of Edith Wharton

This is an old-fashioned but excellently detailed site listing the publication details of all Edith Wharton’s eighty-six short stories – with links to digital versions available free on line.

Edith Wharton at Gutenberg

Free eTexts of the major novels and collections of stories in a variety of digital formats – also includes travel writing and interior design.

Edith Wharton at Wikipedia

Full details of novels, stories, and travel writing, adaptations for television and the cinema, plus web links to related sites.

The Edith Wharton Society

Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University.

The Mount: Edith Wharton’s Home

Aggressively commercial site devoted to exploiting The Mount – the house and estate designed by Edith Wharton. Plan your wedding reception here.

Edith Wharton at Fantastic Fiction

A compilation which purports to be a complete bibliography, arranged as novels, collections, non-fiction, anthologies, short stories, letters, and commentaries – but is largely links to book-selling sites, which however contain some hidden gems.

Edith Wharton’s manuscripts

Archive of Wharton holdings at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© Roy Johnson 2014

Edith Wharton – short stories

More on Edith Wharton

More on short stories

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Jacob’s Room

Jacob’s Room Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.