a selection of web-based archives and resources

This short selection of Jane Austen web links offers quick connections to resources for further study. It’s not comprehensive, and if you have any ideas for additional resources, please use the ‘Comments’ box below to make suggestions.

![]() Jane Austen at Mantex

Jane Austen at Mantex

Biographical notes, book reviews, study guides, videos, and web links.

![]() Jane Austen at Project Gutenberg

Jane Austen at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

![]() Jane Austen at Wikipedia

Jane Austen at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, social background, further reading, and web links.

![]() Jane Austen at the Internet Movie Database

Jane Austen at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors, actors, production, box office, film reviews, trivia, and even quizzes.

![]() Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton

Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton

Resources and a virtual tour at the house where Jane Austen was born. Contains an online shop, educational materials, and links to YouTube videos of conferences and celebration events.

![]() The Jane Austen Centre in Bath

The Jane Austen Centre in Bath

Web site of the exhibition centre, featuring bus tours in the city , a newsletter, online shop, and a Jane Austen quiz.

![]() The Republic of Pemberley

The Republic of Pemberley

Large-scale site covering resources. free eTexts, and discussion groups engaged in ongoing debates about the novels and their characters, plus lists of names and places.

![]() The Complete Works of Jane Austen

The Complete Works of Jane Austen

Kindle eBook single download for £0.74 at Amazon – contains all the novels, plus early works. The equivalent of 2,250 pages of text.

![]() The Jane Austen Society of the UK

The Jane Austen Society of the UK

Web site of the semi-academic society, featuring publications, meetings, and discussion groups – plus items on clothing and forthcoming events.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to Jane Austen

A Hyper-Concordance to Jane Austen

Japan-based research tool which allows you to locate any word or phrase in context – covers all the novels and the early works.

![]() Jane Austen in Japan

Jane Austen in Japan

Home pages of Jane Austen web sites, eTexts of all the novels, discussion groups, and academic resources. The work of Victorian specialist Mitsuharu Matsuoka.

![]() Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts

Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts

Digitised facsimilies of works in her own handwriting – 1,100 pages – see the original manuscripts of the novels in Jane Austen’s own writing, complete with scholarly annotated print versions of the text.

The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen This fully updated edition offers clear, accessible coverage of the intricacies of Austen’s works in their historical context, with biographical information and suggestions for further reading. Major scholars address Austen’s six novels, the letters and other works, in terms accessible to students and the many general readers, as well as to academics. With seven new essays, the Companion now covers topics that have become central to recent Austen studies, for example, gender, sociability, economics, and the increasing number of screen adaptations of the novels.

The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen This fully updated edition offers clear, accessible coverage of the intricacies of Austen’s works in their historical context, with biographical information and suggestions for further reading. Major scholars address Austen’s six novels, the letters and other works, in terms accessible to students and the many general readers, as well as to academics. With seven new essays, the Companion now covers topics that have become central to recent Austen studies, for example, gender, sociability, economics, and the increasing number of screen adaptations of the novels.

© Roy Johnson 2010

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

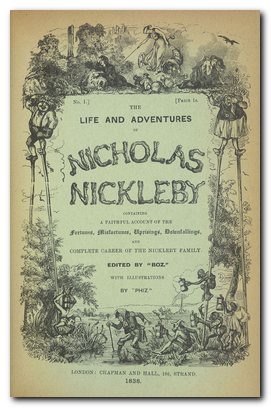

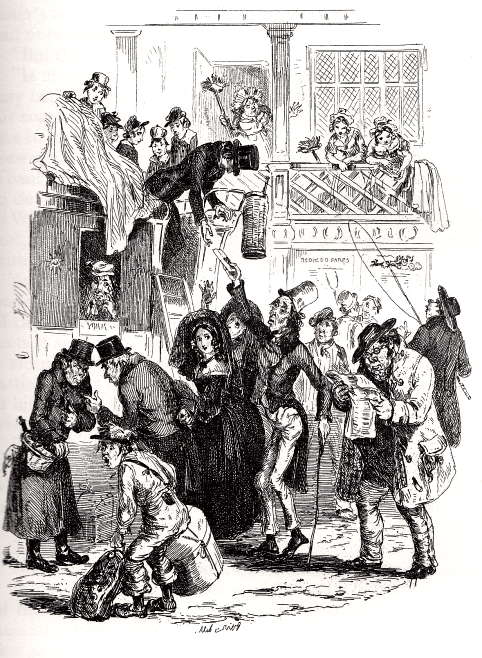

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.