a fantasy romance and mathematical novella

Flatland (1884) is something of a literary curiosity – a Victorian work of science fiction. Its author Edwin Abbott was rather similar to Lewis Carroll – a Cambridge scholar and a clergyman who wrote on language, grammar, and problems of philosophy and mathematics. It’s a difficult work to categorise because it is nearer to a scientific essay than a work of fiction, and yet it does describe a particular world (containing only two dimensions) and it gives an account of the people who live there.

Like Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, Flatland is largely a work of amusing fantasy which pokes fun at some of the conventions of Victorian society at the same time as raising genuinely puzzling issues of geometry and mathematics.

The nearest equivalent in English literature might be Jonathan Swift’s satirical fantasy Gulliver’s Travels (1726) in which a character journeys to strange worlds with different size-related issues and philosophic concepts to his own. Abbott gave his work a sub-title of ‘A Romance in Several Dimensions’. The key term here is ‘Romance’, which as a literary genre is a work featuring a series of happenings which take place outside the natural world.

Flatland – critical commentary

The text purports to be a work written by an inhabitant of Flatland (he is named A Square) in the form of a report of his experiences which have led him to pose some fundamental questions about the nature of reality. The Square has been living in a world of two dimensions, but has visited Lineland (a world of one dimension) and Spaceland – a realm which includes a third dimension and solid objects.

The inhabitants of these separate worlds cannot understand any world that includes a dimension greater in number than that of their own, and even the representative of Spaceland (a Sphere) will not accept the logical outcome of the Square’s experience which is that there might be a fourth dimension.

The Square argues using mathematical logic and Euclidian geometry. The world of Lineland is one-dimensional, and can therefore only generate lines, which have two points or ends. His own world of Flatland has two dimensions, and this generates plane figures – such as triangles and in his own case, a square, which has four points or corners. When he visits Spaceland he is introduced to the concept of a cube, which has eight corners. His argument is Two – Four – Eight – why not Sixteen next? (He actually uses a different sequence).

His fundamental question – and a puzzle which has still not been solved – is that if we live in a world of three dimensions, why cannot we imagine a fourth? It is one of the book’s many ironies that the Square is castigated for even asking such questions – and is eventually imprisoned for raising them. He has written Flatland during seven year’s incarceration – rather like Machiavelli’s Il Principe.

Much of the humour in the book lies in his description of everyday life in Flatland. Social stratification exists to an almost ridiculous degree – with triangles at the bottom of society (tradesmen and soldiers) squares as the middle or professional class next, polygons as the upper class, and finally circles as a ‘priesthood’. So – social status rises as the number of ‘sides’ a person possesses.

Women are straight lines – and have so little status that they are obliged to emit warning sounds so that people do not bump into them and become hurt by their pointed ends. The women do not baulk at the social injustice of their position, because they are ‘devoid of brain-power and have no memory’.

Quite obviously the book is a satire of class divisions in Victorian society, a poking fun at social snobbery, an interesting view on the status of women, and the fear of uprisings amongst lower orders. This is a period after all which was preceded by the Communist Manifesto of 1848, Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859, and the Paris Commune of 1881. But it also raises thought-provoking issues about the mathematics of space.

Flatland – plot summary

As its name suggests, Flatland is a world that is completely flat, and its social orders are ranked according to the number of lines of which each person is composed. Workmen and lower orders are triangles with a very narrow base; professionals and gentlemen are squares; and the nobility are polygons. As the number of sides increase, the status increases, with the highest order a priesthood of circles. Women are single straight lines, and the average height of an inhabitant is eleven inches.

However, women are not without a certain amount of power, because being one-dimensional, they can easily hide themselves, and being shaped like needles, they have sharp ends. They must enter houses only through the woman’s door (always on the East side) and a strict social code requires them to announce their presence at all times – because of their dangerous sharp ends. They are protected from any potential sense of exasperation at this injustice by the fact that they are wholly devoid of brain-power and memory.

In a world of such restricted geometry, how do people tell each other apart? After all, one equilateral triangle is very much like another. The answer is primarily through touching and feeling – though care has to be taken with the ‘brainless vertex of an acute angled Isosceles’.

But recognition by feeling is the practice of only the lower orders. Amongst the upper class of Polygons, recognition by sight is made possible by advanced educational methods (at the University of Wentbridge for instance). This allows members of such classes to recognise each other and makes them suitable for occupying positions of authority in Flatland society.

The watchword of this world is Regularity, and any deviation from it is regarded as an inescapable sign of moral depravity. If the sides of someone’s Square are not equal, he is in danger of being a Rhombus. All such instances are noted at birth and humanely destroyed.

Understandably, life amongst a society of two-dimensional triangles, squares, and circles is remarkably dull. But an Irregular once came up with the idea of making distinctions by using colour. People were painted red at the top and green at the bottom. Unfortunately, this led to a decline in sight recognition, a falling away in class distinctions, and a demand for more power amongst the lower orders of Tradesmen and Soldiers. This led to the passing of the Universal Colour Bill, a politically contentious move that resulted in a conflict which left the Circles triumphant because the Triangles fought amongst themselves. The net result was that the use of colour was banned forever.

In the second part of the book, having outlined the principles of Flatland, the Square has a dream in which he visits Lineland. In this world all the men are short lines and the women are points. They can only ever move along a single line, and no individual Linelander can ever pass another on this line. Marriage and reproduction are arranged by the sound of voices, which makes any form of touching unnecessary: indeed it is forbidden.

The Square tries to convince the King of Lineland that his world and perspectives are strictly limited, but the King cannot conceive of space or anything other than a single straight line.

The Square is then visited by a Sphere who arrives from Spaceland to explain the existence of a third dimension. He tries proving it mathematically and by analogy, but the Square cannot understand and resorts to physical attacks on the Sphere.

The Sphere then takes the Square into Spaceland where he is able to see his entire world of Flatland laid out before him like a map. The Sphere then re-enters the Flatland parliament to pronounce the existence of a third dimension. This is denied, and all those who overheard this heresy are either imprisoned or ‘despatched’.

Back in Spaceland the Sphere explains the nature of a cube to the Square. He is excited by this new knowledge, but then suggests that by analogy of lines, planes, and solids, that there must therefore be a fourth dimension which would make such a world superior to the first three. The Sphere rejects this idea and banishes the Square back to Flatland.

The Square then has a dream in which he is taken by the Sphere into Pointland. This is occupied by single speck who can only ever be conscious of himself, and knows of no existence outside his own. The Sphere encourages the Square’s vision by showing him the generation of geometric solids.

The Square decides to evangelize about the third dimension, starting with his grandson, a Hexagon. But the boy respects thee legal prohibition of such ideas and the experiment is not successful.

The Square tries writing a book about the third dimension, but he is unable to produce any illustrations to demonstrate his beliefs. In frustration he makes a speech at a local Speculative Society meeting relating his experiences. For this he is arrested and sentenced to permanent imprisonment. Seven years later he has written the work called Flatland but regrets that he still hasn’t made a single convert.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2015

Edwin A. Abbott, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp.124, ISBN: 019953750X

find bargains at online bookshops

find bargains at online bookshops At the end of any scholarly writing (an essay, report, or dissertation) you should offer a list of any works you have consulted or from which you have quoted. This list is called a bibliography – literally, a list of books or sources.

At the end of any scholarly writing (an essay, report, or dissertation) you should offer a list of any works you have consulted or from which you have quoted. This list is called a bibliography – literally, a list of books or sources.

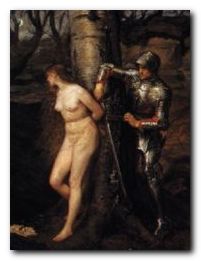

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.