resources, techniques, and issues for literary studies

In the field of literary studies, people have been creating digitized texts and making concordances for quite some time now. But until the advent of the Web it was difficult to get an overview of criticism and scholarship which was easily available. In fact it’s still not easy. As the authors of this excellent guide Literature and the Internet point out, it remains common for the latest work to be made available only in the form of conventionally printed books and the dinosaur publishing methods of scholarly journals.

But at last the Internet is now making ever more material easily available to us, and it is the purpose of this guide to advise students, teachers, and scholars how to make the most of the opportunity to retrieve it. They start with a general survey of the pros and cons of the Internet for literary studies, quite rightly pointing out that despite all its obvious advantages, there are still many shortcomings:

But at last the Internet is now making ever more material easily available to us, and it is the purpose of this guide to advise students, teachers, and scholars how to make the most of the opportunity to retrieve it. They start with a general survey of the pros and cons of the Internet for literary studies, quite rightly pointing out that despite all its obvious advantages, there are still many shortcomings:

It has large and obvious gaps, it cannot cover the literary ground as even a moderately well-stocked library can, and it cannot equal the contemporary appeal of a good bookstore.

In fact the differences between books in libraries and texts on the Net are intelligently explored, before we get down to some practical advice on usability. This centres logically enough on using search engines, and they offer an explanation of the different techniques which can be deployed, as well as alerting users to the differences in kind amongst the sources which might be located.

The centre of the book is an extensive list of resources. These are arranged as web site address – in categories ranging from libraries, journals, literary periods, literary criticism, discussion groups and email distribution lists, to individual authors – from Achebe to Zola – and their home pages.

Mercifully, these lists are annotated with useful evaluative comments, making clear distinctions between sites which are commercial, fan pages, and the results of scholarly research. It’s interesting to note how many of the award-winning sites are the work of dedicated individuals (such as Jack Lynch at Pennsylvania and Mitsuharu Matsuoka in Japan) and departments in little-known colleges in the back of nowhere. Major institutions are noticeably thin on the ground.

I felt reassured that the authors had done their homework, had visited the sites they discuss – and were not frightened of levelling criticism at some quite well known names in the literary establishment. They point out the need for more qualitative evaluation of online resources and web site reviews.

This is followed by advice on the evaluation of sites, including a series of basic questions we can ask on arrival. Is the information accurate? Is it complete? And is there any acknowledgement of the sources being used?

There is also a section for teachers, discussing how computers and the Internet can be used in literary studies, with suggestions (for instance) for hypertext assignments and web essays – though I hope their term Webliographies doesn’t catch on.

They consider the nature of electronic texts – from plain ASCII, through the Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML) and HyperText Markup Language (HTML), and even as far as the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) and Extensible Markup Language (XML).

These are only touched on lightly, with their differences briefly explained, but this is a valuable topic to raise in the consciousness of students and teachers, especially in the light of controversies surrounding the form in which commercial electronic books are being issued.

The guide ends with considerations of the theoretical and political connections between literary studies in an era of digitized text – exploring some of the notions raised in recent years by Jay Bolter, George Landow, and J. Hillis Miller.

They even have some interesting comments to make on the likely impact of Information Technology on academic careers – including the vexed issue of academic publishing, which must surely be due for major convulsions in the next few years.

Many people have argued that it’s now rather pointless issuing printed resource guides which will be quickly outdated. But there is a reason for such publications. The fact is that it’s often quicker to locate information in a book, rather than searching through files or favourites using a browser.

Certainly, I’m very pleased that this book is on my desk, and I look forward to exploring its suggestions and passing on any gems to my own students – who are currently learning how to write, link, zip, and upload their first web essays.

© Roy Johnson 2000

Stephanie Browner, Stephen Pulsford, and Richard Sears, Literature and the Internet: A Guide for Students, Teachers, and Scholars, London/New York: Garland, 2000, pp.191, ISBN: 0815334532

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

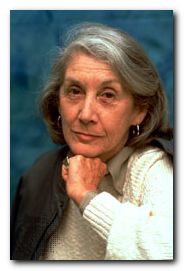

Nadine Gordimer (1923—2014) was born into a privileged white middle-class family in the Transvaal, South Africa. She began reading at an early age, and published her first story in a magazine when she was only fifteen. Her wide reading informed her about the world on the other side of apartheid – the official South African policy of racial segregation – and that discovery in time developed into strong political opposition to apartheid. She attended the University of Witwatersrand for one year. Her first book was a collection of short stories, The Soft Voice of the Serpent (1952). In addition to writing, she lectured and taught at various schools in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. She was awarded the Nobel prize for Literature in 1991.

Nadine Gordimer (1923—2014) was born into a privileged white middle-class family in the Transvaal, South Africa. She began reading at an early age, and published her first story in a magazine when she was only fifteen. Her wide reading informed her about the world on the other side of apartheid – the official South African policy of racial segregation – and that discovery in time developed into strong political opposition to apartheid. She attended the University of Witwatersrand for one year. Her first book was a collection of short stories, The Soft Voice of the Serpent (1952). In addition to writing, she lectured and taught at various schools in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. She was awarded the Nobel prize for Literature in 1991. The Conservationist (1974) concerns a white industrialist who farms his land (with native help) at the weekend and genuinely wants to make his presence a positive contribution. But most of all he wants to preserve his power and his privileged way of life – despite being surrounded by poverty and suffering. He just doesn’t understand that the indigenous population are the natural owners of the land, and the result is disastrous – for him.

The Conservationist (1974) concerns a white industrialist who farms his land (with native help) at the weekend and genuinely wants to make his presence a positive contribution. But most of all he wants to preserve his power and his privileged way of life – despite being surrounded by poverty and suffering. He just doesn’t understand that the indigenous population are the natural owners of the land, and the result is disastrous – for him. Jump Her development as a writer of short stories is wonderful. She starts off in modern post-Checkhovian mode presenting situations which have little drama but which invite the reader to contemplate states of being or moods which illustrate the ideologies of South Africa. Technically, Nadine Gordimer experiments heavily with point of view, narrative perspective, unexplained incidents, switches between internal monologue and third person narrative (rather like Virginia Woolf) and a heavy use of ‘as if’ prose where narrator-author boundaries become very blurred.

Jump Her development as a writer of short stories is wonderful. She starts off in modern post-Checkhovian mode presenting situations which have little drama but which invite the reader to contemplate states of being or moods which illustrate the ideologies of South Africa. Technically, Nadine Gordimer experiments heavily with point of view, narrative perspective, unexplained incidents, switches between internal monologue and third person narrative (rather like Virginia Woolf) and a heavy use of ‘as if’ prose where narrator-author boundaries become very blurred. Selected Stories As her work matured, her style and methods underwent a similar development to those of Virginia Woolf. Some of her stories became more lyrical, more compacted and symbolic, abandoning any semblance of conventional story or plot in favour of a poetic meditation on a theme. There are some stories which make enormous demands upon the reader. Sometimes on first reading it’s even hard to know what is going on. But gradually a densely concentrated image or an idea will emerge – the equivalent of a Joycean ‘epiphany’ – and everything falls into place. Her own collection of Selected Stories are UK National Curriculum recommended reading.

Selected Stories As her work matured, her style and methods underwent a similar development to those of Virginia Woolf. Some of her stories became more lyrical, more compacted and symbolic, abandoning any semblance of conventional story or plot in favour of a poetic meditation on a theme. There are some stories which make enormous demands upon the reader. Sometimes on first reading it’s even hard to know what is going on. But gradually a densely concentrated image or an idea will emerge – the equivalent of a Joycean ‘epiphany’ – and everything falls into place. Her own collection of Selected Stories are UK National Curriculum recommended reading.