an extraordinary life in radical left politics 1905-1941

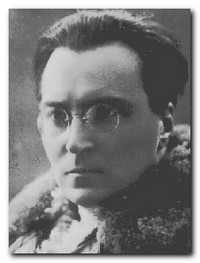

Memoirs of a Revolutionary the autobiography of one of the most remarkable writers in the first half of the twentieth century, and yet his work is hardly known outside a small coterie of admirers. He was a novelist, a poet, a historian, and a political activist. His parents were Russian emigrees; he was born in Belgium; he wrote in French; and he died in political exile in Mexico in 1947. Memoirs of a Revolutionary is a new edition of his political autobiography, which stretches from his youth in Brussels, Lille, and Paris, to his participation in the Russian revolution. It covers his days as a Left Oppositionist, and his eventual exile at the hand of Stalin, to his last desperate years searching for escape on a ‘planet without a passport’ until he was finally able to record this deposition of courage and fortitude.

The first pages are filled with an account of his youthful ideals – mainly centred on a form of libertarianism and anarchism, though recollected from a politically mature point of view. There is remarkably little about his own personal life except his admiration for his father, the fact that he never went to school, and the poor life he eked out as a typesetter and a machine tool draughtsman.

The first pages are filled with an account of his youthful ideals – mainly centred on a form of libertarianism and anarchism, though recollected from a politically mature point of view. There is remarkably little about his own personal life except his admiration for his father, the fact that he never went to school, and the poor life he eked out as a typesetter and a machine tool draughtsman.

His story really begins in Paris, where he lived amongst the poorest, giving language lessons, doing translation work, and writing articles for left-wing newspapers and magazines. It was 1909, and all sorts of political groups were active and (as was often the case) at war with each other – anarcho-syndicalists, Christian democrats, ‘illegalists’ (robbers) and exiled Russian revolutionaries, towards whom Serge felt drawn.

As the editor of a left-wing newspaper he was asked to give evidence against an anarchist gang who carried out a series of desperate raids in 1910. He refused, and was sent to jail for five years. He summarises this next half decade, since the details of his incarceration were transformed into the content of his first documentary novel Men in Prison.

It cannot be stressed too strongly how almost all of Serge’s writing was produced under enormous constraints of time and resources. He wrote whilst in exile, in hiding, and in transit. There were few opportunities for revision, fact-checking, or the sort of re-drafting that most authors take for granted. Everything was produced white-hot – which might account for his direct, compressed, and telegraphic style.

On release from jail he went to Barcelona and took part in the 1917 uprising (something he documents in his second novel, Birth of our Power), but feeling that the real revolution was taking place in Russia, he volunteered for ‘repatriation’ to a country in which he had never set foot, arriving in Petrograd in 1919.

Almost immediately he was recruited into the services of the Third Communist International because of his language skills and knowledge of western Europe, even though at this time he was not a member of the Communist Party.

He committed himself to the Bolsheviks, whilst at the same time being aware of their weaknesses and mistakes – the greatest of which he believed to be the creation of the Cheka, the secret police or state-within-a-state which changed its name frequently but not its pernicious effects.

He paints an unflinchingly honest picture of the Revolution and its aftermath – the disjuncture between official propaganda and the reality of mass starvation, the black market, failed production, and an economy run on useless banknotes.

After a failed attempt to create a self-sufficient commune amongst the famine and poverty in the countryside, he decided that the future of the Revolution lay in the West, and moved to work secretly for the Communist International in Berlin.

He worked as a secret agent, using multiple identities and the cover of a job as journalist and editor. His real job there was to assist the promotion of the German Revolution ‘planned’ for October 1923. This was a period when Marxist orthodoxy thought that revolutions could be planned and organised according to theoretical principles, without troubling to analyse or face any social facts. When the revolution failed to take place, he de-camped to Prague. However, even though conditions there were less severe, he felt unable to act effectively, and so, as a Trotsky supporting oppositionist and at the worst possible time, he loyally returned to Leningrad in 1926.

He worked as a secret agent, using multiple identities and the cover of a job as journalist and editor. His real job there was to assist the promotion of the German Revolution ‘planned’ for October 1923. This was a period when Marxist orthodoxy thought that revolutions could be planned and organised according to theoretical principles, without troubling to analyse or face any social facts. When the revolution failed to take place, he de-camped to Prague. However, even though conditions there were less severe, he felt unable to act effectively, and so, as a Trotsky supporting oppositionist and at the worst possible time, he loyally returned to Leningrad in 1926.

The number of famous people he knew personally is astonishing – political figures such as Zinoviev, Maxim Gorky, Lenin, Trotsky, and Georg Lukacs, but also artists and poets such as Anna Akhmatova, her husband Nikolai Gumilev, plus Alexander Blok and Sergei Yesenin – all of whom he wrote about in his Literature and Revolution.

At times his account reads like a novel, which is not surprising since the narrative is composed of vivid character sketches, scenes recounted from participants’ points of view, sparkling atmospherics and mise en scene, sensational episodes, sudden murders or suicides, and all the time a dramatic tension created by his efforts to survive when all around him are being imprisoned and shot.

If there’s a chapter that’s less briskly paced than the rest, it’s that dealing with the expulsion of the Left-Oppositionists from the Party into exile, jail, and (later) extermination. But Serge’s justification is that of writing as ‘testament’. He passionately wished to place on record the tragic ‘betrayal of the revolution’ exactly as it unfolded.

This period (1926-1928) was followed by the first of the show trials – fabricated crimes in which nobody believed which were used as an excuse to eliminate any traces of criticism of the executive. The punishment for pre-determined outcomes was imprisonment and a bullet in the back of the head.

All of this repression was taking place at the same time as the central committee was responsible for more or less criminal levels of mismanagement of the economy . Famines were created through deliberate stupidity; millions of people were displaced from their land; millions more starved to death. This is the period which forms the background to what many people believe is Serge’s greatest novel, The Case of Comrade Tulayev

In 1933 Serge was finally arrested by the secret police, imprisoned, and when he refused to confess to his non-existent crimes was exiled to Kazakhstan for three years. He records this experience in the third volume of his first trilogy, Midnight in the Century.

He was saved from extinction by the reputation as a writer he had built up in western Europe – particularly France. In the literary conferences called in 1935 and 1936 his case was raised and calls made for his release. Eventually Romain Rolland made a personal appeal to Stalin, and Serge was released.

The police stole his manuscripts and his belongings, but he was deported to Belgium. Even there he was pursued by lies and slander propagated from Moscow. This vilification was accepted by European left-wing parties which were in the process of setting up the Popular Front in co-operation with Stalin against fascism.

Stalin repaid this gullibility with cynical betrayal in the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939 (and its secret protocols) which was rapidly followed by the Nazi invasion of France. Hundreds of artists and intellectuals (as well as refugees from the Spanish Civil War) crowded into southern France hoping to gain visas for the Americas. Serge was in the company of people such as Alma Mahler, André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Leon Feuchtwangler, and Walter Benjamin (who committed suicide on the Spanish border).

Serge made it to Mexico in 1941 – and that’s where his memoir ends, though he was to live another six years in Mexico city – persecuted and shot at by the same agents of Stalin who had murdered Trotsky with an ice pick in 1940. Serge kept on writing until the very end, producing political analyses and also his two greatest novels The Case of Comrade Tulayev and Unforgiving Years. He died of a heart attack in 1947.

If you have never read this classic memoir before, make sure you get this new edition. When it was first released by Oxford University Press in the 1960s one eighth of it was cut on economy grounds. The missing sections have now been restored and the whole of Peter Sedgwick’s remarkable translation is now presented in its entirety for the first time.

© Roy Johnson 2012

Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary, New York: New York Review Books, 2012, pp.521, ISBN: 1590174518

More on Victor Serge

Twentieth century literature

More on biography

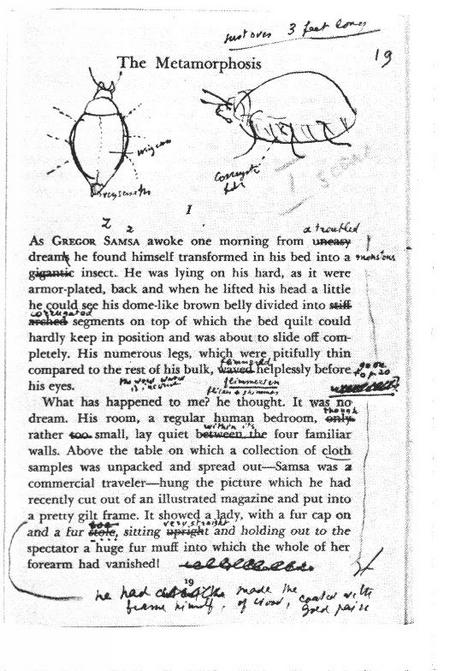

When Gregor’s supervisor arrives at the house and demands Gregor come out of his room, Gregor manages to roll out of bed and unlock his door. His appearance horrifies his family and supervisor; his supervisor flees while his family chases him back into his room.

When Gregor’s supervisor arrives at the house and demands Gregor come out of his room, Gregor manages to roll out of bed and unlock his door. His appearance horrifies his family and supervisor; his supervisor flees while his family chases him back into his room. Later, his parents take in lodgers and use Gregor’s room as a dumping area for unwanted objects. Gregor becomes dirty, covered in dust and old bits of rotten food. One day, Gregor hears Grete playing her violin to entertain the lodgers. Gregor is attracted to the music, and slowly walks into the dining room despite himself, entertaining a fantasy of getting his beloved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. The lodgers see him and give notice, refusing to pay the rent they owe, even threatening to sue the family for harboring him while they stayed there. Grete determines that the monstrous vermin is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. She suggests that they must get rid of it. Gregor retreats to his room and collapses, finally succumbing to his wound, and dying alone.

Later, his parents take in lodgers and use Gregor’s room as a dumping area for unwanted objects. Gregor becomes dirty, covered in dust and old bits of rotten food. One day, Gregor hears Grete playing her violin to entertain the lodgers. Gregor is attracted to the music, and slowly walks into the dining room despite himself, entertaining a fantasy of getting his beloved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. The lodgers see him and give notice, refusing to pay the rent they owe, even threatening to sue the family for harboring him while they stayed there. Grete determines that the monstrous vermin is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. She suggests that they must get rid of it. Gregor retreats to his room and collapses, finally succumbing to his wound, and dying alone. Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

The Trial

The Trial Amerika

Amerika

The Heart of a Dog

The Heart of a Dog Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel

Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel A Country Doctor’s Notebook

A Country Doctor’s Notebook The Fatal Eggs

The Fatal Eggs The Master and Margarita

The Master and Margarita life, works, political persecution

life, works, political persecution The Heart of a Dog

The Heart of a Dog

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller