a chronicle of events, literature, and politics

1920. League of Nations established; Oxford University admits women;

D.H. Lawrence, Women in Love; Nobel prize – K. Hamsun (N).

1921. Irish Free State proclaimed; extreme inflation in Germany; Fatty Arbuckle scandal in US; Nobel prize – Anatole France (F).

1922. Fascists march on Rome under Mussolini; Kemel Ataturk founds modern Turkey; T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land; James Joyce, Ulysses; Katherine Mansfield, The Garden Party; Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus; John Galsworthy, The Forsyth Saga; Nobel prize – J. Benavente (Sp).

1923. Charleston craze; BBC begins radio broadcasting in the UK; William Walton Facade; Nobel prize – W.B. Yeats (Ir).

1924. First UK Labour government formed under Ramsey MacDonald (lasts nine months); Deaths of Lenin, Franz Kafka, and Joseph Conrad; Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain; E.M. Forster, A Passage to India; Nobel prize – W. Raymont (P).

1925. John Logie Baird televises an image of a human face; Webern Wozzeck; Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf; Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway; Nobel prize – George Bernard Shaw (UK).

1926. UK General Strike; first demonstration of television in UK; Fritz Lang, Metropolis; Nobel prize – G. Deledda (I).

1927. Lindbergh flies solo across Atlantic; first talkie film – Al Jolson in ‘The Jazz Singer’; Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse; Nobel prize – Henri Bergson (Fr).

Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Literature in English is a new reference guide to English-language writers and writing throughout the present century, in all major genres and from all around the world – from Joseph Conrad to Will Self, Virginia Woolf to David Mamet, Ezra Pound to Peter Carey, James Joyce to Amy Tan. Includes entries on literary movements, periodicals, and over 400 individual works, as well as articles on some 2,400 authors, plus a good introduction by John Sutherland.

Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Literature in English is a new reference guide to English-language writers and writing throughout the present century, in all major genres and from all around the world – from Joseph Conrad to Will Self, Virginia Woolf to David Mamet, Ezra Pound to Peter Carey, James Joyce to Amy Tan. Includes entries on literary movements, periodicals, and over 400 individual works, as well as articles on some 2,400 authors, plus a good introduction by John Sutherland.

1928. Women in UK get same voting rights as men; Death of Thomas Hardy; first Oxford English Dictionary published; penicillin discovered;

D.H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover; Evelyn Waugh, Decline and Fall; Nobel prize – S. Undset (N).

1929. Slump in US, followed by collapse of New York Stock Exchange; Start of world economic depression; Second UK Labour government under MacDonald;

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own; first experimental television broadcast; Kurt Weil The Threepenny Opera; Nobel prize – Thomas Mann (G).

1930. Mass unemployment in UK; Death of D.H. Lawrence.

William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying; Nobel prize – Sinclair Lewis (US).

1931. Resignation of UK Labour government, followed by formation of national coalition government; Empire State building completed in New York; Virginia Woolf, The Waves; Nobel prize – R.A. Karfeldt (S).

1932. Hunger marches start in UK; scientists split the atom; air conditioning invented; Aldous Huxley, Brave New World; Nobel prize – John Galsworthy (UK).

1933. Adolf Hitler appointed Chancellor of Germany; first Nazi concentration camps; prohibition ends in US; Radio Luxembourg begins commercial broadcasts to UK; George Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London;Jean Vigo, L’Atalante; Nobel prize – Ivan Bunin (USSR).

1934. Hitler becomes Dictator; Evelyn Waugh, A Handful of Dust; Samuel Beckett, More Pricks than Kicks; Nobel prize – Luigi Pirandello (I).

1935. Germany re-arms; Italians invade Abyssinia (Ethiopia); Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet; Nobel prize – not awarded.

1936. Death of George V in UK, followed by Edward VIII, who is forced to abdicate; Stalinist show trials in USSR; Civil War in Spain begins; Germany re-occupies the Rheinland; BBC begins television transmissions; Aaron Copland El Salon Mexico; Nobel prize – Eugene O’Neil (USA).

1937. Neville Chamberlain UK prime minister; Destruction of Guernica;

George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier; Nobel prize – Roger Martin du Gard (Fr).

Twentieth-century Britain is an account of political, industrial, commercial, and cultural development in England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. It’s particularly strong on the changing face of government, and it also relates issues of the day to the great writers and artists of the period. This ‘very short introduction’ series offers a potted account of the subject in handy pocket-book format, with plenty of suggestions for further reading.

Twentieth-century Britain is an account of political, industrial, commercial, and cultural development in England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. It’s particularly strong on the changing face of government, and it also relates issues of the day to the great writers and artists of the period. This ‘very short introduction’ series offers a potted account of the subject in handy pocket-book format, with plenty of suggestions for further reading.

1938. Germans occupy Austria; Chamberlain meets Hitler to make infamous Munich ‘agreement’ to prevent war; Samuel Beckett, Murphy; John Dos Passos, USA; Nobel prize – Pearl S. Buck (USA).

1939. Fascists win Civil War in Spain; Stalin makes pact with Hitler; Germany invades Poland; Britain and France declare war on Germany; helicopter invented;

James Joyce, Finnegans Wake; Nobel prize – F.E. Silanpaa (Fi).

1940. Germany invades north-west Europe; Fall of France; British troops evacuated from Dunkirk; Battle of Britain; Start of ‘Blitz’ bombing raids over London; Churchill heads national coalition government; assassination of Trotsky; Nobel prize – not awarded.

1941. Germany invades USSR; Japanese destroy US fleet at Pearl Harbour; USA enters the war; siege of Leningrad; Deaths of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf; Orson Wells, Citizen Kane; Nobel prize – not awarded.

1942. Battle of Stalingrad; Battle of Midway; Beveridge report establishes basis of modern Welfare State; T-shirt invented; Nobel prize – not awarded.

1943. Anglo-American armies invade Italy; Warsaw uprising; Nobel prize – not awarded.

1944. D-Day invasion of France; ball-point pens go on sale; German V1 and V2 rockets fired; R.A. Butler’s Education Act; Aaron Copland Appalachian Spring; Nobel prize – J.V. Jensen (Da).

1945. End of war in Europe; Atomic bombs dropped on Japan; first computer built; microwave oven invented; United Nations founded; huge Labour victory in UK general election; Atlee becomes prime minister, George Orwell, Animal Farm; Nobel prize – G. Mistral (Ch).

1946. Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ speech; Nuremberg war trials; bikinis introduced; United Nations opens in New York; Nobel prize – Herman Hesse (Sw)

1947. Marshall Plan of aid to Europe; Jewish refugees turned away by UK; Polaroid camera invented; coal and other industries nationalised in UK; transfer of power to independent India, Pakistan, and Burma. Thomas Mann, Doktor Faustus; Nobel prize – A. Gide (Fr)

1948. Berlin airlift; state of Israel founded; Railways and electricity nationalised in UK; Bevan launches National Health Service in UK. Nobel prize – T.S. Eliot (UK)

1949. East Germany created; Mao Tse Tung declares Republic of China; NATO founded; Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex; George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty Four; Nobel prize – W. Faulkner (USA)

© Roy Johnson 2009

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

Le Grand Meaulnes

Le Grand Meaulnes We

We Manhattan Transfer

Manhattan Transfer Auto da Fe

Auto da Fe Miss Lonelyhearts

Miss Lonelyhearts Darkness at Noon

Darkness at Noon The Master and Margarita

The Master and Margarita Invisible Man

Invisible Man The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps The Tin Drum

The Tin Drum Dr Zhivago

Dr Zhivago Wide Sargasso Sea

Wide Sargasso Sea One Hundred Years of Solitude

One Hundred Years of Solitude The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum

The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum The Golden Gate

The Golden Gate The Conservationist

The Conservationist

Mary

Mary Other novels such as

Other novels such as

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch

August 1914

August 1914 Lenin in Zurich

Lenin in Zurich

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

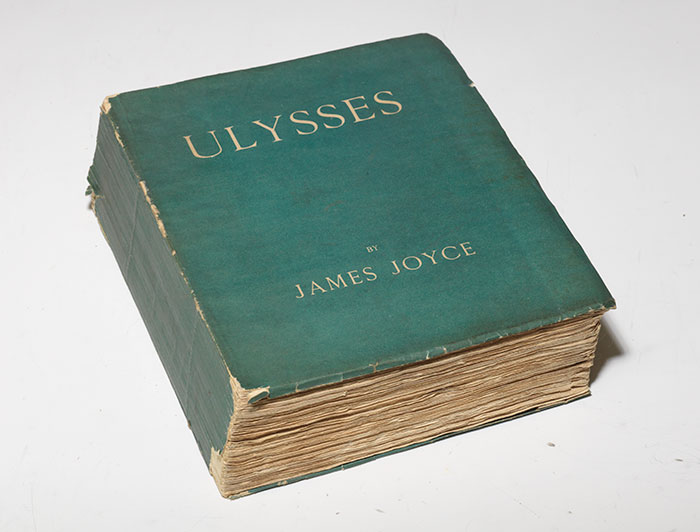

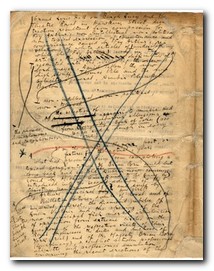

One factor which complicates the textual history of the novel is that Joyce continued working on it, even after it had been published. The printer in Dijon had made errors; Ezra Pound had made cuts and changes to the episodes in circulation via magazines, and Joyce revised multiple copies of his work which had been produced by non-professional typists from his near-illegible handwritten manuscripts.

One factor which complicates the textual history of the novel is that Joyce continued working on it, even after it had been published. The printer in Dijon had made errors; Ezra Pound had made cuts and changes to the episodes in circulation via magazines, and Joyce revised multiple copies of his work which had been produced by non-professional typists from his near-illegible handwritten manuscripts. The most spectacular of these attempts was that piloted by the German scholar Hans Walter Gabler, who proposed to ‘recover’ the original text by comparing surviving manuscripts, corrected proofs, and existing editions. He produced what was called a synoptic version, which was issued as Ulysses: The Corrected Text in 1986. This was designed to put an end to all uncertainties regarding the accuracy of the text.

The most spectacular of these attempts was that piloted by the German scholar Hans Walter Gabler, who proposed to ‘recover’ the original text by comparing surviving manuscripts, corrected proofs, and existing editions. He produced what was called a synoptic version, which was issued as Ulysses: The Corrected Text in 1986. This was designed to put an end to all uncertainties regarding the accuracy of the text.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

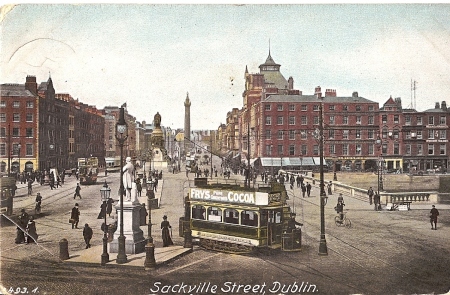

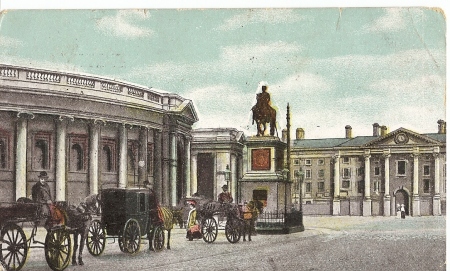

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.