biographical studies of five early English modernist painters

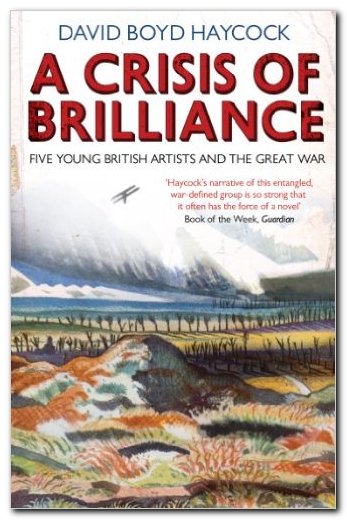

A Crisis of Brilliance is a study of five talented British painters in the early modernist period who were contemporaries at the Slade School of Art – Dora Carrington, Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, Richard Nevinson, and Paul Nash – a generation which their Professor of Drawing Henry Tonks described in the phrase which gives the book its title.

Author David Boyd Haycock’s approach is to present the biographical sketches like a relay race. With one artist profile under way, he passes on to the next, until they are all at work simultaneously. This makes the book eminently readable and it also reinforces the fact that the members of this group, though from very different backgrounds, were all developing their talents in the same artistic environment, and at the same time.

Stanley Spencer was from a small village in Berkshire on the Thames. He had virtually no formal education, and was introduced to the world of art via the patronage of a local landowner’s wife. His drawing skills were so developed that he was allowed to skip the Slade’s formal entrance requirements of a written exam.

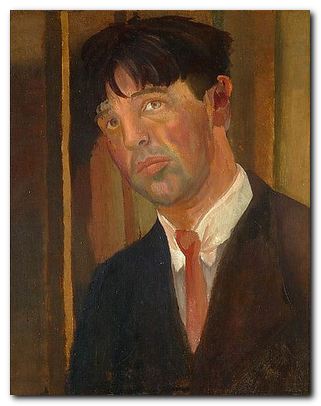

Mark (Max) Gertler was the youngest son of poor Jewish immigrants who settled in London’s East End. He left school early and worked in a stained glass studio to pay his tuition fees at Regent Street Polytechnic. Via social connections he was fortunate enough to meet fellow painter Isaac Rosenberg and the gallery owner William Rothenstein, through whose influence he was admitted to the Slade.

The students of this generation graduated from sketching plaster casts in the Antiques Room to the Life Class where they were allowed to draw nude models (women) for the first time. It is interesting to note that conversation between male and female students was frowned upon by the School, and any discussion with the models strictly forbidden.

Stanley Spenser missed out on these late afternoon life classes because he had to catch the train back home. His fellow student Richard ‘Chips’ Nevinson satirised this provincialism by calling Spenser ‘Cookham’ – the name of his home village. It was a nickname which stuck with him throughout the rest of his time at the Slade.

The next arrivals in 1910 included Paul Nash, and Dora Carrington. Nash was another educational tragedy whose only talent was drawing. He paid his own fees for the one year he spent at the Slade, and made rapid progress despite the caustic tutorial method of Henry Tonks.

Carrington too was someone whose background almost inhibited any form of intellectual development, but her skill at portraiture gave her access to the premier art college in England and the bohemian life in Bloomsbury that she craved. She had her hair cropped, wore men’s clothes, and became quite avant garde in her behaviour if not in her style of painting.

One interesting feature (which might be worth further exploration) is that none of these people were particularly gifted in an academic sense. Spencer had almost no formal education, Nevinson went to a public school, from which he emerged with nothing but contempt for its values, Paul Nash was an educational duffer, Gertler left school at fourteen, and Carrington’s education didn’t begin until she arrived at the Slade.

Nineteen hundred and ten was a good year to be there, because as Virginia Woolf later observed ‘On or about December 1910, human character changed’. The occasion to which she referred was the exhibition of post-Impressionist paintings organised at the Grafton Galleries in Mayfair by her friend Roger Fry, the newly appointed Professor of Art History at the Slade.

The exhibition was enormously controversial. Henry Tonks actually pleaded with students to stay away from the Galleries altogether lest they be ‘contaminated’. However, although the Slade group were enthusiastically modern in their behaviour, the post-Impressionists did not greatly affect their style of painting – with the exception of Carrington, who felt that her whole life had been changed at this point. Stanley Spencer carried on painting as before and was more enthusiastic about the early Italian masters than ever.

Nevinson and Gertler became involved in a triangular relationship with Carrington – one that continued long after they had all left the Slade. Paul Nash discovered his visionary appreciation of the English countryside, Spencer retired to Cookham to produce allegorical works such as John Donne Arriving in Heaven and Gertler was the envy of his colleagues, earning £1,000 a year painting society portraits.

In addition to the painters, Haycock also includes studies of the patrons who bought and collected their works. The most outstanding amongst these was Eddie Marsh, personal secretary to Winston Churchill (at that time First Lord of the Admiralty) who inherited money paid in compensation to the family of his relative Spencer Percival, the only British prime minister to be assassinated. Marsh called it ‘the murder money’ and used it to buy paintings.

When war broke out in 1914 the responses of the Slade group varied from Paul Nash immediately enlisting (for Home Guard duties) to Gertler’s absolute refusal to countenance the conflict in any way. Gertler escaped into the countryside with fellow refusenik D.H.Lawrence, later moving to Hampstead where he became friendly with Lytton Strachey and other members of the Bloomsbury Group.

Dora Carrington followed suit via a different route, and ended up falling in love with Lytton Strachey in a famous incident when she crept into his bedroom at night to cut off his long beard with a pair of scissors. Strachey was completely homosexual, but that did not prevent them going on to have a lifelong relationship, living together.

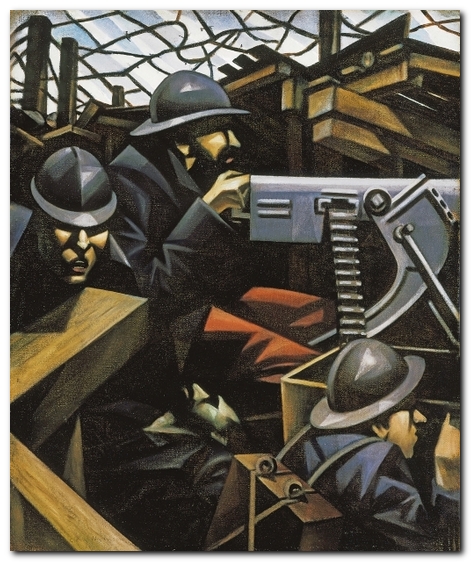

As the mass slaughter of the war continued unabated into 1916, more bodies were required to fill the trenches. The Conscription Acts meant that any male between eighteen and forty-one was obliged to enlist for service. This led to people registering as conscientious objectors, and their reactions to the war were summed up by Gertler in what was to become his most famous painting, Merry-Go-Round. Nevinson had a similar success with his painting La Mitrailleuse.

After leaving the war as invalids, both Nevinson and Nash were recalled to military service, and only with great difficulty managed to secure positions as war artists, but this helped them both to stay away from the slaughter in the front lines. Meanwhile Carrington finally gave in to Gertler’s sexual demands, yet at the same time established her curious sexless menage with Lytton Strachey. They moved into a large mill house at Tidmarsh in Berkshire.

Stanley Spencer was pinned down in the Balkans whilst suffering from the irony that he had been asked to contribute to a war memorial. When the war finally ended he was given rapid transit back home – only to find that plans for the memorial had meanwhile been scrapped. However, he threw himself into the completion of one of his masterpieces, Swan Upping at Cookham which had been left unfinished at his conscription.

After the war Carrington managed to complicate her life even further by marrying Ralph Partridge, with whom her partner Lytton Strachey was in love. It was her way of keeping them all together. She also went on to have an affair with her new husband’s best friend, Gerald Brenan, then passed on to relationships with women. She continued painting but did not exhibit, and was generally depressed. Her suffering came to an end when Strachey died of stomach cancer in 1932 and she shot herself, unwilling to go on living without him.

Gertler’s life after the war (or in his case, after Carrington) was a series of ups and downs. He was penniless one minute, successful the next. He married a former Slade student and they had a son, but the marriage was not a success. By the late nineteen-thirties, feeling that his personal and his professional life were failures, and learning that Hitler was persecuting Jews, he gassed himself in his studio.

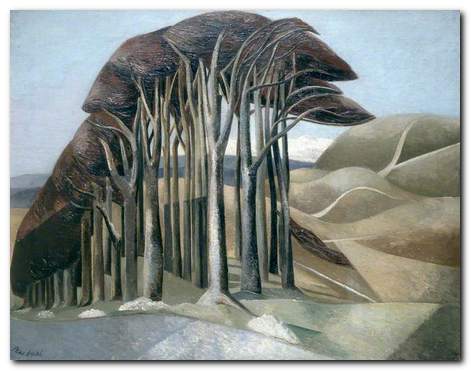

Nevinson and Nash became ‘war artists without a war’. Nevinson’s post-war years were tortured – mainly by his rancour at not being celebrated, and he died embittered in 1946. Nash on the other hand emerged from the war with what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder. He was unsure how to develop any further sense of modernism and reverted to traditional landscape painting. There was a brief flirtation with the surrealists, but that came to nothing. Unlike Nevinson, he did become a war artist again during 1939-45, but his health gave out and he died of heart failure in 1946.

Stanley Spencer was the longest-lived of this group. In 1925 he suddenly married a fellow Slade student Hilda Carline and he discovered a new subject for some of his later works – conjugal sex. The sudden change to his normally puritanical lifestyle presaged major disruptions. First he moved back to Cookham trying to recapture (unsuccessfully) some of his earlier feelings and artistic inspiration. Then he met Patricia Preece, a former Slade student who was living in the village with her lover Dorothy Hepworth.

Spencer proposed a menage a trois with Patricia, but his wife refused and divorced him. He immediately married Patricia who equally refused to cohabit or to have any sexual relations with him. So he ended up with a wife, an ex-wife, and two children to support. When he signed over the deeds of his own home to her, his wife forced him out, and perhaps not surprisingly he had a nervous breakdown. He was commissioned as a war artist during 1939-45 and completed paintings of shipbuilding on the Clyde. But his main creative impetus was spent, and he died in 1956, the same year as he received a knighthood.

Haycock’s elegant study quite rightly got rave reviews when it was first published. It is well structured and written, beautifully illustrated, and like all successful studies of this kind leaves you with a desire to know more about this cultural period and these quasi-tragic figures who contributed so much to English visual culture.

© Roy Johnson 2015

David Boyd Haycock, A Crisis of Brilliance, London: Old Street Publishing, pp.386, ISBN: 1906964327

More on art

More on media

More on design

The Art of Bloomsbury

The Art of Bloomsbury Bloomsbury Rooms: Modernism, Subculture, and Domesticity

Bloomsbury Rooms: Modernism, Subculture, and Domesticity The Art of Dora Carrington

The Art of Dora Carrington The Bloomsbury Artists: Prints and Book Designs

The Bloomsbury Artists: Prints and Book Designs Vision and Design

Vision and Design Charleston: A Bloomsbury House and Garden

Charleston: A Bloomsbury House and Garden The Art of Duncan Grant

The Art of Duncan Grant