Adrian Mole meets Bloomsbury

Richard Kennedy started work at the Hogarth Press when he was sixteen. He had been a complete failure at Marlborough School, and was fixed up with the job through a family connection as a special favour, starting work at one pound a week. His memoirs (and atmospheric line illustrations) were produced many years later, and they take great delight in contrasting the youth’s naive enthusiasm and his bewilderment with the sophisticated milieu into which he had been transported.

Leonard Woolf ran an enterprise in the Hogarth Press which was commercially very successful, and Kennedy joined it at a time in the 1920s when the work of Virginia Woolf (particularly Orlando) and Vita Sackville-West (All Passion Spent) were virtually best-sellers. But his approach is to depict these intellectual giants as they were seen by a sixteen year old boy. He was far more interested in learning how to chat up girls than the lofty aspirations of his employers. He contrives to present an ‘Emperor’s New Clothes’ approach to all things Bloomsbury, and the result is a sort of Adrian Mole version of events.

Leonard Woolf ran an enterprise in the Hogarth Press which was commercially very successful, and Kennedy joined it at a time in the 1920s when the work of Virginia Woolf (particularly Orlando) and Vita Sackville-West (All Passion Spent) were virtually best-sellers. But his approach is to depict these intellectual giants as they were seen by a sixteen year old boy. He was far more interested in learning how to chat up girls than the lofty aspirations of his employers. He contrives to present an ‘Emperor’s New Clothes’ approach to all things Bloomsbury, and the result is a sort of Adrian Mole version of events.

The saintly Virginia Woolf, who at that time was producing some of the most advanced texts of literary modernism, is pictured as she would appear to a young teenager:

She looks at us over the top of her steel-rimmed spectacles, her grey hair hanging over her forehead and a shag cigarette (which she rolls herself) hanging from her lips. She wears a hatchet-blue overall and sits hunched in a wicker armchair with her pad on her knees and a small typewriter beside her.

His employer, the indefatigable Leonard Woolf, who ran the whole enterprise with rigorous efficiency, is cut down to size in a similar fashion:

After lunch we all straggled home over the Downs. LW stopped to have a pee in a very casual way without attempting any sort of cover. I could see that this was a part of his super-rational way of living.

But for all the naive self deprecation, you know that Kennedy is well connected. He is in fact from the same social milieu as the people he describes, as he reveals in a throwaway remark on a visit to St Ives::

The picnic over, we returned to Talland House – curiously enough, the scene of Virginia Woolf’s first successful novel, To the Lighthouse. Her parents had rented the house from my aunt’s parents .

The book is decorated by spidery but very evocative drawings which capture the mood of the era and the spirit of the text. Amazingly, they were drawn from memory in the 1970s, yet capture both the period and the principal characters very well.

It’s a slight book to say the least, but it’s very amusing and it throws light onto the workings of what was a very successful publishing business – and for Bloomsbury Group enthusiasts it has some delicious thumbnail sketches of the principals, as well as even floor plans of the rooms at the Hogarth Press, showing who was cooped up where. Full marks to Hesperus Press for bringing this delightful book back into print.

© Roy Johnson 2011

Richard Kennedy, A Boy at the Hogarth Press, London: Hesperus Press, 2011, pp.90, ISBN 1843914611

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on biography

And yet for all that he takes a jokey line, he offers lots of interesting insights – such as the reasons why some software lasts, unlike hardware which on average is replaced every three years. It’s a shame, because he is clearly well informed and at some points has interesting things to say about technological developments and even the philosophy of the internet – but his efforts are dissipated by a lack of focus. He throws off ideas and sketches topics every few pages which warrant a book in themselves, but he can’t quite make up his mind if he’s a historian of technology or a commentator on business methods.

And yet for all that he takes a jokey line, he offers lots of interesting insights – such as the reasons why some software lasts, unlike hardware which on average is replaced every three years. It’s a shame, because he is clearly well informed and at some points has interesting things to say about technological developments and even the philosophy of the internet – but his efforts are dissipated by a lack of focus. He throws off ideas and sketches topics every few pages which warrant a book in themselves, but he can’t quite make up his mind if he’s a historian of technology or a commentator on business methods.

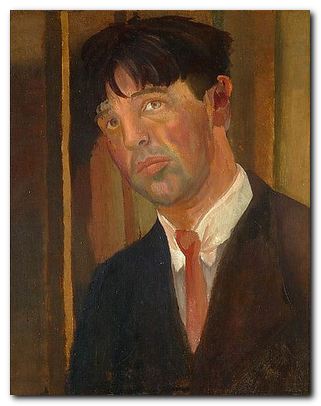

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

Strangely enough, there was no Art Nouveau school of painting, mainly because it constituted an approach to design. It was in the realm of posters, woodcuts, illustrated books, and typography that it made its greatest impact, and there are excellent examples of posters by Lautrec, Mucha, and Bonnard. These were works which gave birth to the figure that came to symbolise fin de siecle Paris and la Belle Epoque – a young woman with serpentine hair, clad fashionably in jewelled or feathered headgear and wearing immense sweeping skirts, all of which flowed abundantly to fill the frame of the picture. It’s amazing to realise that these romantically stylised images were being used to advertise such mundane objects as bicycles, wine, household soap, and cigarette papers.

Strangely enough, there was no Art Nouveau school of painting, mainly because it constituted an approach to design. It was in the realm of posters, woodcuts, illustrated books, and typography that it made its greatest impact, and there are excellent examples of posters by Lautrec, Mucha, and Bonnard. These were works which gave birth to the figure that came to symbolise fin de siecle Paris and la Belle Epoque – a young woman with serpentine hair, clad fashionably in jewelled or feathered headgear and wearing immense sweeping skirts, all of which flowed abundantly to fill the frame of the picture. It’s amazing to realise that these romantically stylised images were being used to advertise such mundane objects as bicycles, wine, household soap, and cigarette papers.