the rise of Russian modernism 1863-1922

Camilla Gray was a young and pioneering scholar of Russian modernist art. She was a former ballet dancer, with no academic background. She married Oleg Prokoviev (the composer’s son) and died tragically young at the age of only thirty-five. And yet she established a body of work on Russian art in 1962 which was quickly appreciated in other European countries. Her original impulse, fuelled by admiration for the modernist work of Malevich and Tatlin, was to look into the tradition out of which such revolutionary art had grown. The Russian Experiment in Art was the culmination of her life’s work.

There was little information around in the 1960s when she began her research, which is what makes her achievement so remarkable. The first part of the cultural process she documents is the development of a Russian middle class in the late nineteenth century. Mamontov, who made his money builidng the railway from Archangel to Murmansk, established an artists’ colony based in Slavophile Moscow (not europhile St Petersburgh). From this many artistic themes were developed, including the connection between painting and the theatre, and a desire to make aesthetics socialy useful. The standout character she highlights from this period (of whom I had not heard before) is Mikhail Vrubel.

There was little information around in the 1960s when she began her research, which is what makes her achievement so remarkable. The first part of the cultural process she documents is the development of a Russian middle class in the late nineteenth century. Mamontov, who made his money builidng the railway from Archangel to Murmansk, established an artists’ colony based in Slavophile Moscow (not europhile St Petersburgh). From this many artistic themes were developed, including the connection between painting and the theatre, and a desire to make aesthetics socialy useful. The standout character she highlights from this period (of whom I had not heard before) is Mikhail Vrubel.

Meanwhile, towards the end of the nineteenth century, a group centred in St Petersburg focussed their desires for a new Russian art around the production of a magazine, called ‘World of Art’. Like most avant gard magazines it was short-lived, but it included work by Leon Bakst, Sergei Diaghilev, and Alexander Benois. They had allowed themselves to be influenced by the latest developments in France, Germany, and Italy and thus represented a cosmopolitanism which was common in much of modernist art.

Following the 1905 revolution there was a vigorous period of art collecting by wealthy patrons which resulted in Russian artists having direct contact with the work of post-impressionists – and Matisse and Picasso in particular made a big impression on the Russian avant garde.

Her study then moves on to two seminal figures who helped to bridge the gap between traditional Russian folk art and modernism – Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova. They both went on to become stage designers, working for Sergei Diaghilev. It’s interesting to note as an aside that it was quite common for artists to design scale model sets and costumes for stage productions which had not taken place, and often never would.

Natalia Goncharova 1910

Many of the individual movements in Russian art were taking place at the same time, and being developed at a dizzying pace. Larionov’s experiments in Rayonnism (the Russian equivalent of Italian Futurism) were painted alongside his neo-primitivist pictures of peasant life. When Larionov and Goncharova left to tour Europe with The Ballets Russe, the baton of further developments seemed to be taken up by the next two major figures to emerge – Malevich and Tatlin.

Malevich went from paintings in a Cubo-Futurist style in 1912-1913 to his totally abstract compositions in Suprematism only two years later. And in roughly the same period Vladimir Tatlin progressed from stylised but conventional paintings to the abstract three-dimensional constructions, of which his Monument to the Third International is the most famous. (It should be remembered that this was only ever a model for a building intended to be twice the height of the Empire State building.)

The artistic dynamics which created these many styles didn’t prevent factional disputes between rival tendencies, and at the ‘Last Futurist Painting Exhibition’ Malevich and Tatlin actually held up the opening by having a fist-fight brawl until they were separated by Alexandra Exter.

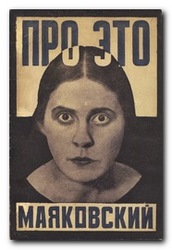

In 1917 the Revolution gave artists both a political impetus and an opportunity to link their art to socially useful purposes, which many of them did with great enthusiasm – particularly leftists such as Alexander Rodchenko and El Lissitzky.

It is with their pioneering work in typography and photo-montage that the book ends. Too soon, I felt – but perhaps mercifully so, because within a few years of their fresh and optimistic work of the early 1920s, the whole of the heroic phase of Soviet communism was crushed under the stifling diktats of centralist ideology, and all ‘art’ was reduced to the drab banalities of Socialist Realism.

Camilla Gray does her best to persuade us that the Russian versions of Cubism and Futurism were quite different than their French and Italian counterparts. The visual evidence in this richly illustrated volume suggest otherwise. She also has the naive critical habit of taking what artists say about themselves and their work at face value.

However, it’s easy to see why this pioneering study The Russian Experiment in Art is so highly regarded. She gives specific names and dates to artists, individual works of art, and exhibitions almost as if she was present whilst they were taking place. There is a full critical apparatus attached to the work, and this has been updated and expanded by Marion Burleigh-Motley, a specialist in Russian art at New York University. In short, this is a serious update of a major work of art history – available for the price of a couple of drinks.

© Roy Johnson 2010

Camilla Gray, The Russian Experiment in Art 1863-1922, London: Thames and Hudson, 2007, pp.324, ISBN 0500202079

More on art

More on media

More on design

Spurred on by the success of the site in the last year or so, the owners have decided to publish a book which encapsulates all their best design principles. I immediately thought it would be a collection of the ‘best of’ articles they have published. But no, it’s more a condensation of their general wisdom – and is much better for that. A chapter on ‘Best Design Features 2009’ would be out of date before the book came into your hands. .

Spurred on by the success of the site in the last year or so, the owners have decided to publish a book which encapsulates all their best design principles. I immediately thought it would be a collection of the ‘best of’ articles they have published. But no, it’s more a condensation of their general wisdom – and is much better for that. A chapter on ‘Best Design Features 2009’ would be out of date before the book came into your hands. .

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice.

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice. Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.

Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.

Gavin Ambrose & Paul Harris,

Gavin Ambrose & Paul Harris,