tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

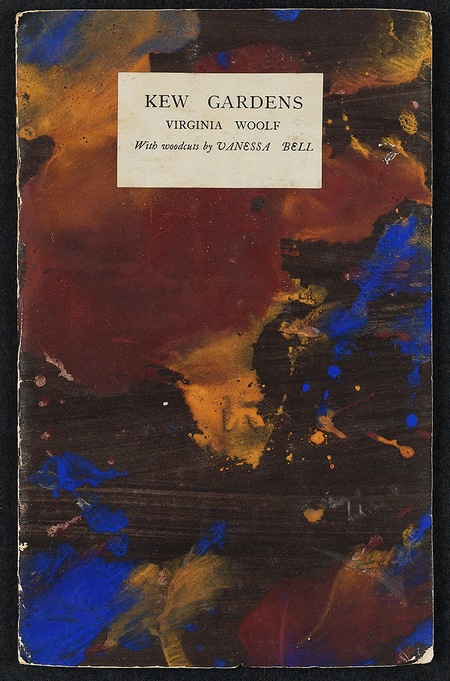

Kew Gardens was written in 1917 and first appeared in a handbound edition of twenty-four pages Virginia Woolf published herself at the Hogarth Press. Her partner in this kitchen table enterprise, husband Leonard Woolf, describes the genesis of the edition.

In 1918 we printed two small books: Poems by T.S. Eliot and Kew Gardens by Virginia. Of Kew Gardens we printed about 170 copies (the total sold of the first edition was 148). We published it on 12 May 1919 at 2s. When we started printing and publishing with our Publication No. 1, we did not send out any review copies, but in the case of Prelude [by Katherine Mansfield], Tom’s Poems, and Kew Gardens we sent review copies to The Times Literary Supplement. By 31 May we had sold forty-nine copies of Kew Gardens. On Tuesday 27 May, we went to Asham and stayed there for a week, returning to Richmond on 3 June. In the previous week a review of Kew Gardens had appeared in the Literary Supplement giving it tremendous praise. When we opened the door of Hogarth House, we found the hall covered with envelopes and postcards containing orders from booksellers all over the country. It was impossible for us to start printing enough copies to meet these orders, so we went to a printer, Richard Madely, and got him to print a second edition of 500 copies, which cost us £8 9s. 6d. It was sold by the end of 1920 and we did not reprint.

It was the Woolf’s first artistic and commercial success as publishers, and gave them the confidence to back their own literary judgement(s) in the stream of publications which followed. The story was eventually collected with her other experimental short prose pieces written between 1917 and 1925, available as The Haunted House. The first edition of Kew Gardens had text only on the right-hand pages, which were hand trimmed by Virginia Woolf herself with a pen knife. Surviving copies of this first edition now trade at £2,000 or more.

Kew Gardens – a flower bed

Kew Gardens – critical commentary

Meaning

One of the features of literary modernism embraced by Virginia Woolf was that of the author’s absence from the text. What this means is that along with writers such as James Joyce, Katherine Mansfield, and others she believed that authors should not intrude into their own work, advising and guiding the reader, but should stay outside it, letting the story speak for itself. Thus, we are not given any obvious clues about what to think of the characters or the events, but must make up our own minds about what they ‘mean’. This idea goes back to the French novelist Flaubert.

This absence of authorial guidance is one factor which makes for difficulty of interpretation. Another in this case is that we are only presented with fragments or snatches of events upon which to base our judgement. We do not have time to get to know the characters (certainly not in this story) before they move off out of it again.

Woolf is also one of many modernist writers who took an interest in revealing how people deceive themselves and act in what is called bad faith – that is, not admitting the truth about themselves or their relationship with others. But this issue, combined with the lack of authorial comment, means that we may only have the character’s word to go by, and that character may not be a reliable witness or commentator.

Understanding

All four couples mentioned in the story seem lacking in purpose or objective, and this casts them in a somewhat negative light. This is particularly so when contrasted with the almost heroic manner in which the movements of the snail are described.

Simon and his wife Eleanor are introduced by pointing to a physical gap (of about ‘six inches’) between them. He is ‘strolling carelessly’ whilst she is walking ‘with greater purpose’, which draws attention to the differences in their attitudes. Eleanor is also the one keeping an eye on their children. The point thatWoolf seems to be making here is that they are not in harmony with each other – as the subsequent narrative confirms.

In fact the very next sentence reinforces the idea that he is excluding himself from their joint enterprise. He keeps his distance in front of her ‘purposely’ even if he is unconscious of doing so. That is, he is not aware of the consequences of his own actions.

We are then presented with his reverie concerning a similarly hot summer day fifteen years earlier on which he ‘begged’ Lily to marry him. He focuses his attention on a dragonfly whose irregular movements echo those of the butterflies with which the people in the Gardens have just been compared and those at the end of the story which are likened to a ‘shattered marble column’. These subtle repetitions of image are the sort of poetic devices Woolf introduced into prose as a substitute for conventional linearity of plot or story.

Simon also focuses on Lily’s shoe buckle, and we note that she moves her foot ‘impatiently’. Woolf does not tell us what Lily is thinking: the narrative is related from Simon’s point of view. But we guess from this that she is not comfortable with his solicitations. She is another woman with whom Simon is not in harmony.

He then transfers his hopes onto the dragonfly alighting on a red flower, which in its turn echoes the flowers which have been described at the beginning of the story. Simon even thinks ‘there, on that leaf’ in the present time of the narrative, and which will be mentioned again at tits end.

But the dragonfly does not alight, Lily refuses him, and he reflects that this is a good thing (‘happily not’) because otherwise he would not be with his wife and children now. This is a rationalisation, or worse, bad faith. And just in case we are in any doubt, his subsequent actions are confirmation.

First of all he informs his wife that he has just been thinking about another woman – which is either gauche or completely tactless, Certainly Eleanor greets his announcement with silence, from which it is reasonable to assume that she is offended. Then he makes matters worse by referring to her as ‘the woman I might have married’. The term might is ambiguous here, but it seems that he means the woman he could have married – when in fact we know that she turned him down. Simon is creating a lie.

Woolf is offering this character sketch as an example of the sort of selfishness and self-deception she often perceives in people, especially in men. It is also telling that Simon’s memory of the past is contrasted by Eleanor’s – which turns out to be a kiss on the back of the neck – given her by ‘an old grey-haired woman with a wart on her nose, the mother of all my kisses, all my life’.

Woolf is pointing to the distance between the two people in this particular couple – which is paralleled by similar failures in communication between the two old men, the two women, and the young couple who are the last to walk by the flower bed.

Structure

Virginia Woolf minimises the elements of plot or narrative in this story, but she strengthens other elements by way of compensation. In Kew Gardens there is a very strong element of pattern, repetition, and shape which strengthen the aesthetic harmony of the piece.

The four couples who pass by the flower bed constitute a pattern. They are different in kind (a married pair, a young and old man, two elderly ladies, and a courting couple) yet they all share the same characteristic – a failure of communication.

Simon and Eleanor’s thoughts are pointed in completely opposite directions; the older man is deranged and cannot communicate sensibly with his escort William; the two women talk streams of rubbish, and one of them even stops listening to the other; and the young couple are too immersed by their ‘courtship’ of each other to communicate freely. Thus the underlying theme of communication breakdown reinforces the structure of the composition.

In addition, the subject of the story oscillates between the flower bed and the people walking past, and in each case there is a small transitional link carrying the narrative from one to the other. There is also a marked contrast between the two subjects. The human beings are fairly desultory and without purpose, but the snail is described in terms which stress its purposefulness. ‘It appears to have a definite goal’ and it ‘considers every possible method of reaching its goal’.

Finally, the story begins and ends with a description of the flowers and their petals. The first paragraph ends: ‘Then the breeze stirred rather more briskly overhead and the colour was flashed into the air above’ whilst the final paragraph of the story concludes ‘and the petals of myriads of flowers flashed their colours into the air’.

Literary impressionism

Virginia Woolf was very interested in painting (her sister Vanessa Bell designed the covers for her publications) and in her writing she often attempts to capture the sense of life through atmosphere, light, and shade. For that reason her work is often compared to that of the Impressionist school of painters such as Monet, Pissaro, and Renoir.

It is fairly obvious in Kew Gardens that she is trying to create the ambiance of a hot day in summer by describing both the vegetation in the Gardens and the people strolling through them. In fact at one point she even depicts the dappled effects of light and shade which was a favourite technique of the Impressionists. As Eleanor and Simon walk away from the flower bed with their children, they

looked half transparent as the sunlight and shade swam over their backs in large trembling irregular patches.

This effect reinforces the very transitory nature of the visitations made by the four pairs of people – the married couple, the two men, two elderly women, and the courting couple. They walk past the flower bed just for a moment, and then pass onIf Kew Gardens has a story in the conventional sense, then that is all it is – four couple walk past a flower bed one summer afternoon.

But in fact that is only one half of the story. The other half is what goes on in the flower bed itself. And you might notice that the insect and plant life is described both in scrupulous detail and in a manner which is in some senses sharply contrasted with the human life in the story.

Kew Gardens – study resources

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

![]() A Haunted House and Other Short Stories – Kindle edition

A Haunted House and Other Short Stories – Kindle edition

![]() A Haunted House and Other Short Stories – Hogarth reprint – AMazon UK

A Haunted House and Other Short Stories – Hogarth reprint – AMazon UK

![]() Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

![]() Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon UK

Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon UK

![]() Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon US

Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon US

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

![]() Kew Gardens – an alternative reading

Kew Gardens – an alternative reading

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

Kew Gardens – story synopsis

The story opens with a description of an oval flower bed in Kew Gardens on a hot day during July. The colourful flowers and vegetation are evoked in very fine detail.

A man and his wife walk past the flower bed with their children. Each of them is lost in reveries about the past. He thinks about a woman he might have married: she remembers being kissed by an old lady.

The story returns to ground level, where amidst the plants a snail is making slow progress in its movements through the vegetation.

A young man appears escorting an elderly man who is talking incessantly and walking with disturbed, uneasy movements. He is clearly deranged,

They are followed by two elderly women who are gossiping meaninglessly to each other, one of them not listening to the other, and then they move on.

Meanwhile the snail is making some progress in its journey through the undergrowth, all of which is seen from the snail’s point of view.

The last people to pass by the flower bed are a courting couple who are flirting with each other, and preparing to have tea together, vaguely conscious of immanence in life.

Finally the narrative returns to the flower bed, which is visited by a bird and then a swarm of butterflies, and the point of view gradually rises to evoke the busy life of London as a whole.

Virginia Woolf podcast

A eulogy to words

Principal characters

| — | a snail |

| Simon | Eleanor’s husband |

| Eleanor | Simon’s wife |

| William | a young man |

| — | a demented elderly man |

| — | two elderly women |

| — | a youth in his prime |

| Trissie | his girl friend |

first edition 1917

Further reading

![]() Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

![]() Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

![]() Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

![]() John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

![]() Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

![]() Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

![]() Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

![]() Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

![]() Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

“I feel certain that I am going mad again.”

Other works by Virginia Woolf

Between the Acts (1941) is her last novel, in which she returns to a less demanding literary style. Despite being written immediately before her suicide, she combines a playful wittiness with her satirical critique of English upper middle-class life. The story is set in the summer of 1939 on the day of the annual village fete at Pointz Hall. It describes a country pageant on English history written by Miss La Trobe, and its effects on the people who watch it. Most of the audience misunderstand it in various ways, but the implication is that it is a work of art which temporarily creates order amidst the chaos of human life. There’s lots of social comedy, some amusing reflections on English weather, and meteorological metaphors and imagery run cleverly throughout the book.

Between the Acts (1941) is her last novel, in which she returns to a less demanding literary style. Despite being written immediately before her suicide, she combines a playful wittiness with her satirical critique of English upper middle-class life. The story is set in the summer of 1939 on the day of the annual village fete at Pointz Hall. It describes a country pageant on English history written by Miss La Trobe, and its effects on the people who watch it. Most of the audience misunderstand it in various ways, but the implication is that it is a work of art which temporarily creates order amidst the chaos of human life. There’s lots of social comedy, some amusing reflections on English weather, and meteorological metaphors and imagery run cleverly throughout the book.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction contains all the classic short stories such as The Mark on the Wall, A Haunted House, and The String Quartet – but also the shorter fragments and experimental pieces such as Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street. These ‘sketches’ (as she called them) were used to practice the techniques she used in her longer fictions. Nearly fifty pieces written over the course of Woolf’s writing career are arranged chronologically to offer insights into her development as a writer. This is one for connoisseurs – well presented and edited in a scholarly manner.

The Complete Shorter Fiction contains all the classic short stories such as The Mark on the Wall, A Haunted House, and The String Quartet – but also the shorter fragments and experimental pieces such as Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street. These ‘sketches’ (as she called them) were used to practice the techniques she used in her longer fictions. Nearly fifty pieces written over the course of Woolf’s writing career are arranged chronologically to offer insights into her development as a writer. This is one for connoisseurs – well presented and edited in a scholarly manner.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf – web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

Book reviews, Bloomsbury related issues, links, study resources, news of conferences, exhibitions, and events, regularly updated.

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of her work, fiction and non-fiction publications, photograph albumns, list of biographies, and external web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Selected eTexts of her novels and stories in a variety of digital formats.

![]() Woolf Online

Woolf Online

An electronic edition and commentary on To the Lighthouse with notes on its composition, revisions, and printing – plus relevant extracts from the diaries, essays, and letters.

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search texts of all the major novels and essays, word by word – locate quotations, references, and individual terms

![]() Orlando – Sally Potter’s film archive

Orlando – Sally Potter’s film archive

The text and film script, production notes, casting, locations, set designs, publicity photos, video clips, costume designs, and interviews.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury – including Gordon Square, Gower Street, Bedford Square, Tavistock Square, plus links to women’s history web sites.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Bulletins of events, annual lectures, society publications, and extensive links to Woolf and Bloomsbury related web sites

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

Charming sound recording of radio talk given by Virginia Woolf in 1937 – a podcast accompanied by a slideshow of photographs.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephen compiled a photograph album and wrote an epistolary memoir, known as the “Mausoleum Book,” to mourn the death of his wife, Julia, in 1895 – an archive at Smith College – Massachusetts

![]() Virginia Woolf first editions

Virginia Woolf first editions

Hogarth Press book jacket covers of the first editions of Woolf’s novels, essays, and stories – largely designed by her sister, Vanessa Bell.

![]() Virginia Woolf – on video

Virginia Woolf – on video

Biographical studies and documentary videos with comments on Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the social background of their times.

![]() Virginia Woolf Miscellany

Virginia Woolf Miscellany

An archive of academic journal essays 2003—2014, featuring news items, book reviews, and full length studies.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – short stories

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

Virginia Woolf – life and works

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first.

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first. Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Sons and Lovers

Sons and Lovers Women in Love

Women in Love