tutorial, commentary, study resources, characters, and plot

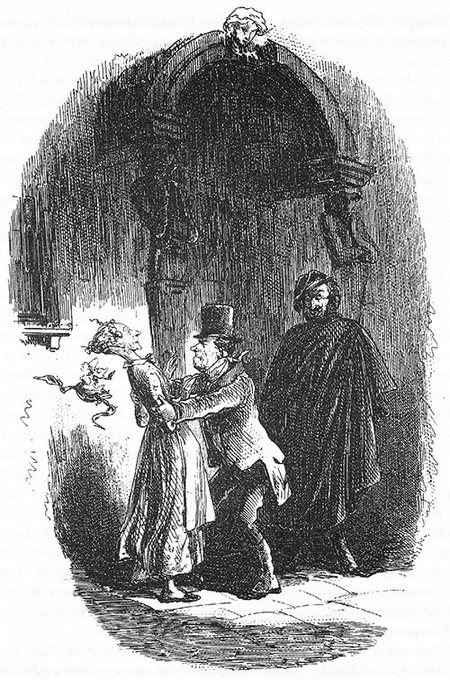

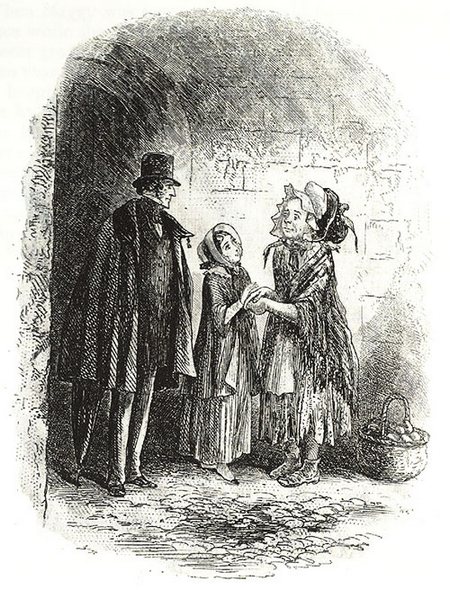

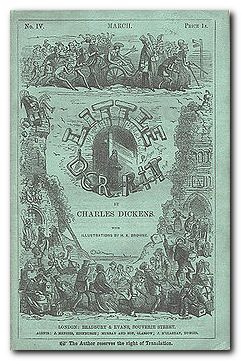

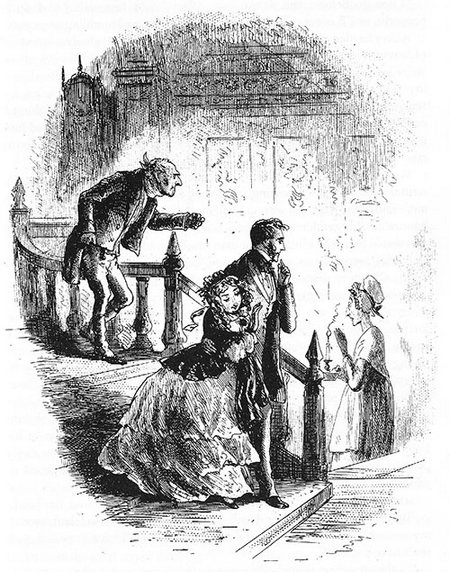

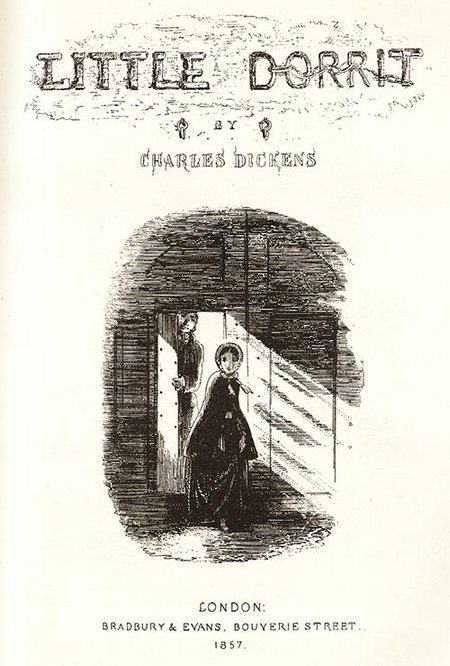

Little Dorrit was first published in monthly instalment between December 1855 and June 1857, then in a single volume by Bradbury and Evans in 1857, with original illustrations by Hablot K. Browne. It was a huge and immediate success, with monthly instalments selling 35,000 copies in 1856.

Little Dorrit – critical commentary

The principal theme

The overarching metaphor for the entire novel is that of the prison and imprisonment. The novel begins with two men in prison – Rigaud and Cavalletto – in Marseilles. In the very next chapter, a collection of English travellers (the Meagles family and Clennam) are ‘imprisoned’ in quarantine (against the plague) in the same location.

In fact the novel also ends in a prison during the hot months of summer, when debtor Arthur Clennam is nursed by Little Dorrit in the late stages of his illness. When Clennam finally gets home, it is to find his ‘mother’ imprisoned by her bitterness and self-inflicted martyrdom in the family home which has become almost a tomb.

William Dorrit has been in the Marshalsea prison for twenty-three years – so long that he has become its self-appointed father figure. His daughter Amy has even been born in the prison, and is the love object of John Chivery, the prison warder’s son.

When the newly-enriched Dorrits embark on their Grand Tour of Europe, even the convent at the summit of the Great Saint Bernard Pass is likened to a prison – because it is divided into Spartan cells.

There are also various forms of psychological imprisonment – in addition to Mrs Clennam. William Dorrit is first of all imprisoned in delusions of grandeur. He ignores the fact that he has been in a debtor’s prison for almost a quarter of a century, and gives himself lofty airs and graces, extracting handouts (which he calls ‘tributes’) from his fellow prisoners.

When Dorrit actually does become rich, he is almost equally deluded by his snobbish exercises in social climbing. He seeks out the wealthy and the fashionable in society, and conveniently ignores the fact that he is an ex-jailbird. It is significant that at the height of these endeavours, his psychological collapse takes him back to where he has come from when he makes a bizarre speech at the dinner given by Mrs Meagles, at which he believes he is back in the Marshalsea Prison.

In fact Dickens takes the metaphor of the prison to universal proportions when he creates one of his many pictures of London:

The last day of the appointed week touched the bars of the Marshalsea gate. Black, all night, since the gate had clashed on Little Dorrit, its iron stripes were turned by the early-glowing sun into stripes of gold. Far aslant across the city, over its jumbled roofs, and through the open tracery of its church towers, struck the long bright rays, bars of the prison of this lower world.

Ingratitude

A strong secondary theme running through the events of the narrative is ingratitude. It is often counterpoised against the saintly devotion of Little Dorrit and the gentlemanly code of honour that Arthur Clennam tries to maintain – often to his own disadvantage.

Tip and Fanny, Little Dorrit’s brother and sister, show no gratitude for what is done for them. Amy secures employment for her sister, who returns the favour with nothing but bad grace, and Tip goes from one job that is found for him to another – without a word of thanks or shame that he is so feckless. He even reproaches Clennam for not lending him money when he asks for it – though after an illness in Rome he appears to reform morally, offering to make his sister Amy rich, even if he inherits all his father’s money.

Henry Gowan displays similar levels of selfishness and a cynical unconcern for others. He has had a self-indulgent life, has run up personal debts, pretends to aspirations as a ‘painter’, yet claims he is ‘disappointed’ that his family has not done more for him. There is very little resolution to this strand of the novel.

Plot weaknesses

When Affrey Flintwinch hears noises and has ‘dreams’, the reader may realise that she is sensing that something is wrong in the house of Clennam. But Dickens does not really play fair with the reader, who can have no notion of a twin brother for Jeremiah Flintwinch, a fact which is concealed for the majority of the novel. This is the literary equivalent of pulling a rabbit out of a conjurer’s hat.

Similarly, Pancks’ uncovering of Dorrit’s inheritance is something the reader can know nothing about – it comes as something of a deus ex machina to move the plot forward from Book the First (Poverty) to Book the Second (Riches). There is no really satisfying explanation of how Panks located the information, and his own account is muddied by his idiosyncratic manner of speaking.

The full complications of the plot are exposed by Blandois in his blackmail attempt on Mrs Clennam at the dramatic climax of the novel. This too is resolved in a slightly unsatisfactory manner.

Whilst Blandois is something of a stock villan himself, complete with hooked nose and black moustache, his aquisition of the important information regarding the Clennam family secret comes from Flintwitch’s twin brother who he has met at a quayside tavern in Amsterdam. This is pushing the bounds of coincidence and improbability to an unacceptable degree for most modern tastes.

Another weakness is the lack of continuity between important elements and characters being introduced in the early part of the narrative, then not taken up again until much later. Of course this is a now-recognised feature of the serial novel – multiple plot lines and characters used as points of interest to drag readers through the part-issues of the whole work.

Little Dorrit – Study resources

![]() Little Dorrit – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon UK

Little Dorrit – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Little Dorrit – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon US

Little Dorrit – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon US

![]() Little Dorrit – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

Little Dorrit – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Little Dorrit – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

Little Dorrit – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() Little Dorrit – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

Little Dorrit – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() Charles Dickens – biographical notes

Charles Dickens – biographical notes

![]() Little Dorrit – eBook at Project Gutenberg

Little Dorrit – eBook at Project Gutenberg

![]() Little Dorrit – audioBook at LibriVox

Little Dorrit – audioBook at LibriVox

![]() Little Dorrit – complete Hablot K. Browne illustrations

Little Dorrit – complete Hablot K. Browne illustrations

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens – Amazon UK

![]() Little Dorrit – York Notes at Amazon UK

Little Dorrit – York Notes at Amazon UK

![]() Little Dorrit – Brodie’s Notes at Amazon UK

Little Dorrit – Brodie’s Notes at Amazon UK

![]() Little Dorrit – Audio book (unabridged) – Amazon UK

Little Dorrit – Audio book (unabridged) – Amazon UK

![]() Charles Dickens’ London – interactive map

Charles Dickens’ London – interactive map

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Charles Dickens – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Charles Dickens – Amazon UK

Little Dorrit – plot summary

Book the First – Poverty

Ch. I John Baptist Cavalletto and Monsieur Rigaud are being held in jail in Marseilles during a hot summer. Rigaud recounts the history of his marrying a rich young local widow, and her sudden death following an altercation between them. He is taken away to face trial.

Ch. II Arthur Clennam is returning from twenty years in China following the death of his father. He is in quarantine with the Meagles family, to whom he relates his harsh upbringing. Mr Meagles recounts the history of their daughter Pet and her curious maid, Tattycoram. On release they make their adieux, and Tattycoram complains ambiguously to the mysterious Miss Wade.

Ch. III Clennam arrives home on a miserable Sunday to a cheerless reception from his puritanical mother. He possesses a watch given to him by his dying father. Servant Mrs Flintwinch relates her curious marriage to Jeremiah and the fact that Clennam’s childhood sweetheart is now available as a widow. Clennam notices Little Dorrit in his mother’s room.

Ch. IV Affrey Flintwinch has a ‘dream’ in which she sees her husband in a meeting with his double who takes away a metal box. Flintwinch catches his wife and threatens her in a menacing manner.

Ch. V Clennam announces to his mother that he is quitting the family business, and in spite of her venomously wrathful response, he asks her if his late father has ever wronged somebody (which he suspects may be the case). His mother immediately appoints Flintwinch as a business partner. Affrey then tells Clennam about Little Dorrit, which arouses his curiosity.

Ch. VI Although Dorrit is not named, the chapter recounts the history of his twenty-five year incarceration in the Marshalsea Prison. It includes the birth of his daughter Amy in the prison. He stays there so long that he becomes the ‘father of the Marshalsea’, to whom fellow inmates give ‘tributes’ (charitable gifts) when they are released.

Ch. VII The history of Amy (Little Dorrit) and her childhood in the prison. She becomes a guardian to her helpless father, and finds employment for her elder sister Fanny as a dancer. Her brother ‘Tip’ fails in every job he is given, and ends up back in the prison as a debtor.

Ch. VIII Outside the prison, Clennam meets Frederick Dorrit (‘Dirty Dick’) who introduces him to his brother William. Clennam meets Amy and her brother and sister. Dorrit explains the system of ‘Testimonials’, and Clennam gives him money. However, Clennam is caught by the night curfew and is forced to spend the night in the prison. He perceives a link between the Dorrit family and his mother.

Ch. IX Clennam receives Amy at the prison, then they walk out into London, where he quizzes her about the connection with his family. She asks for understanding and tolerance for her father, and reveals that his main creditor is Tite Barnacle. On return they meet her simple and undeveloped friend Maggy.

Ch. X Clennam visits the Circumlocution Office in search of information regarding Dorrit’s creditors. Barnacle Junior refers him to Tite Barnacle in Grosvenor Mews, who refers him back to the Office, where various officials are completely obstructive. He meets Mr Meagles, who is frustrating the enquiries of the patient inventor Doyce. They all repair to Bleeding Heart Yard, where Doyce lives.

Ch. XI Rigaud has been acquitted at his trial, and escaped to avoid public censure. He meets Cavalletto at a boarding house in Chalons-sur-Soane and seeks to enlist him as a servant again – but Cavalletto escapes early the following morning.

Ch. XII Clennam, Meagles, and Doyce visit Bleeding Heart Yard in search of Plornish, who finds it hard to obtain work (and has been in prison himself). Mrs Plornish explains their connections with Little Dorrit which come via Casby, the landlord of the Yard. Clennam arranges via Plornish to pay off Tip’s debt to a dubious horse trader.

Ch. XIII Clennam then visits the Casby household, and realises that Casby is an empty fraud. He also meets Panks, the rent-collector, then his childhood sweetheart Flora Casby, who has become an embarrassing featherbrain. He feels so sorry for her that he accepts an invitation to stay for what turns out to be a comic dinner. Afterwards he walks with Panks into the city and comes across Cavalletto, who has been run over by a mail coach.

Ch. XIV Little Dorrit arrives at Clennam’s lodgings with Maggy at midnight to ‘thank’ him for releasing Tip. She thinks Mrs Clennam has learned the secret of her prison home from Flintwinch. Amy and Maggy are locked out of the prison because it is so late, and spend a grim and frightening night in the streets, where they encounter a woman who is about to commit suicide.

Ch. XV Affrey Flintwinch again encounters mysterious noises in the house, then overhears a dispute between her husband and Mrs Clennam. She is menaced by her husband once again.

Ch. XVI Clennam walks to Twickenham to see Mr Meagles, and on his way. meets Doyce, who needs a business partner for his enterprise. Clennam thinks of falling in love with Minnie (Pet) Meagles, but then decides against it. Tattycoram has been in touch with Miss Wade, who has offered her a position if she needs one. Clennam asks Meagles for advice regarding a plan to join Doyce as partner.

Ch. XVII The following day Clennam meets Henry Gowan at the ferry and immediately becomes jealous of him. The company are joined by Barnacle Junior for dinner, and Doyce reveals Gowan’s dubious background and feckless nature to Clennam, who remains deeply conflicted in his feelings about Pet.

Ch. XVIII John Chivery, the Marshalsea lock-keeper’s son has nursed a life-long romantic passion for Amy. He presents cigars to William Dorrit on a Sunday, then locates Amy on the Iron Bridge, where he wishes to declare his feelings for her. But she refuses to let him do so.

Ch. XIX William Dorrit tries to encourage his bedraggled brother Frederick to smarten himself up. He then notes that the lock-keeper Mr Chivery is not as friendly to him as usual and complains to Amy about Frederick’s descent into wretchedness. He falls into a passion of maudlin self-pity, alternating with periods of delusory self-aggrandisement. Amy watches over him throughout the night.

Ch. XX Amy goes to visit her sister at the theatre where she is a dancer. Fanny takes Amy to see Mrs Merdle whose son has proposed marriage to her. Fanny has misled Mrs Merdle into thinking that she comes from a distinguished family. However, Mrs Merdle thinks it would be social suicide to have her son marry socially beneath him and she bribes Fanny to stay away from the boy, who is a hopeless booby. Fanny complains unjustly to her sister in a patronising manner.

Ch. XXI Mr Merdle’s prodigious wealth and his position in Harley Street at the pinnacle of Society. His step son Sparkler is a feckless wastrel who proposes marriage to young women at random. Merdle throws a lavish reception attended by prominent people from the Law, the Church, and the Treasury who toady up to him and dine at his expense whilst he consumes very little himself. Although his physician confirms that there is nothing physically wrong with him, Merdle suffers from a mysterious ‘complaint’.

Ch. XXII Dorrit becomes critical of Clennam because his ‘testimonials’ are not sustained. Gatekeeper Chivery asks Clennam to visit his wife, who reveals that her son has fallen into a permanent fit of despair because he has been rejected by Amy. She pleads with Clennam to intercede with Amy on her son’s behalf. Clennam meets Amy on the bridge, then Maggy, who bears begging letters from Dorrit and Tip addressed to Clennam. He pays Dorrit, but not Tip.

Ch. XXIII Meagles arranges for Clennam to become Daniel Doyce’s business partner. Clennam is visited at the workshop in Bleeding Heart Yard by Flora Casby and Mr F’s Aunt. Flora flirts with Clennam, claiming that she wants to help Little Dorrit. Pancks reveals that Casby had nothing to do with Little Dorrit’s placement with Mrs Clennam and he asks Clennam for information on the Dorrit family. Clennam tells him, on condition that Panks reveals any new information about them. Panks then collects rents in the Yard.

Ch. XXIV Little Dorrit visits the Casby home where Flora says she wants to employ her. Flora paints an over-romanticised picture of herself and Clennam designed to establish a claim on him. After-dinner Panks interviews Amy: he knows all about her family and claims to know what her future will be. After this he becomes omnipresent in the lives of the Dorrits.

Ch. XXV Panks’s second life lodging with the Ruggs in Pentonville. He invites John Chivery to a Sunday lunch and introduces him to Anastasia Rugg who has sued a local baker for breach of promise. Panks also befriends Cavalletto who is now lodging in Bleeding Heart Yard.

Ch. XXVI Clennam cannot sustain his resolution not to be attracted to Pet Meagles, and he cannot fight down his dislike for his rival Henry Gowan. The cynic Gowan patronises Doyce and invites Clennam to visit his mother at Hampton Court. Over dinner there is a snobbish exchange on the nation’s decline and ancestor worship of the Barnacles and Stiltstalkings. Mrs Gowan quizzes Clennam about Pet, claiming that the Meagles are social climbing, trying to make an alliance with her family. Clennam tries to explain that this is not the case but she refuses to believe him.

Ch. XXVII Meagles suddenly reports to Clennam that Tattycoram has gone missing. They trace her to an old house in Mayfair where she is staying with Miss Wade. Meagles entreats her to return to the family but she refuses. Miss Wade behaves scornfully to the two men and reveals that she like Tattycoram is an orphan with no name.

Ch. XXVIII Meagles advertises for Tattycoram in the newspaper but in return only receives begging letters from the public. Clennam and Daniel Doyce go to the Meagles for the weekend, where Clennam meets Pet by the river. She plucks at Clennam’s heart strings by telling him how happy she is to be in love with Henry Gowan. Clennam thinks that she is destined to be unhappy but swallows his unrequited love and congratulates her.

Ch. XXIX Mrs Clennam quizzes Little Dorrit about Panks who was taken to visiting the house more frequently. Little Dorrit tells her nothing. When Panks leaves, Affrey accidentally shuts herself out of the house, but Blandois (Rigaud) suddenly appears in the street and climbs through a window to let her in.

Ch. XXX Blandois and Jeremiah Flintwinch appear to recognise each other when they meet. Blondois has arrived with a letter of introduction and credit from Paris. He wishes to meet Mrs Clennam who is surprisingly open and even confessional with him. He asks Flintwinch to show him around the house, tries (and fails) to get him drunk, and predicts that they will become close friends. Yet next day he goes straight back to Paris.

Ch. XXXI Mrs Plornish’s impoverished father Old Nandy is let out of the workhouse for his birthday treat. Little Dorrit takes him to the prison, meeting her sister Fanny en route who snobbishly thinks Amy is lowering the family’s social standing. The birthday treat is paid for by Clennam who joins them whilst Dorrit loftily patronises Old Nandy. Tip appears and insults Clennam for not lending him money. Dorrit reproaches his son.

Ch. XXXII Clennam seeks an audience with Little Dorrit at the prison and asks her why she has been avoiding him. He fails to see that she is in love with him. He wants to know if she’s hiding anything from him, which she denies. She feels completely embarrassed by his revelations regarding his feelings for Pet Meagles. Panks suddenly appears, takes Clennam to meet Mr Rugg, and reveals that they have uncovered some important documents.

Ch. XXXIII Mrs Gowan explains to Mrs Merdle why and how she has ‘consented’ to the marriage of her son Henry to Pet Meagles. The truth is that they want her son Henry’s debts paid off. Mrs Merdle then reproaches her husband for being too preoccupied with his work. Edmund Sparkler appears and confirms that he is a dimwit who knows virtually nothing.

Ch. XXXIV Although Clennam is still trying to be honourably fair to his rival Henry Gowan he is disturbed when Gowan reveals his cynical and disappointed views at not having succeeded socially and not been better treated by his family. The marriage goes ahead and is attended by many of the Barnacles.

Ch. XXXV Panks reveals the he has uncovered a huge legacy due to Dorrit. He has financed the search with his own money plus loans from Rugg and Casby. Clennam goes to the Casby house where Flora is as garrulous as ever but kind to Amy. Clennam and Little Dorrit go to the prison and break the news to Dorrit, who promises to repay everybody.

Ch. XXXVI Dorrit immediately becomes imperious with the prison Marshal; Fanny buys dresses and bonnets; and Tip re-pays Clennam’s loan in a condescending manner. There is a celebratory feast for all the Collegians then a grand departure at which they forget Amy. Clennam brings her down from her room where she has fainted.

Book the Second – Riches

Ch. I The Dorrits, the Gowans, and Blandois all converge in a convent at the summit of the Saint Bernard Pass on route to Italy. Little Dorrit meets Pet Meagles (now Mrs Gowan) for the first time, befriends her, and shows her a message from Clennam.

Ch. II Mr Dorrit has hired the lofty Mrs General at great cost to complete the education of his two daughters. Mrs General is devoid of opinions and is entirely composed of surface polish.

Ch. III Fanny and Edward snobbishly reproach Amy for helping Mrs Gowan and for her connection with Clennam, who they now regard as beneath them socially. Dorrit mediates but thinks Clennam should cease to be acquainted with their family. Dorrit protests when he finds someone in their hotel rooms, but backs down when outfaced by Mrs Merdle. Amy now feels separated from her father and oppressed by the presence of a maid. The party eventually reaches Venice where Amy travels around alone.

Ch. IV Little Dorrit writes to Clennam telling him she has met Pet Meagle and thinks she should have a better husband than Henry Gowan. She also tells him that she misses the Dorrit of old, and that she wishes to be remembered as she herself was previously. She asks Clennam not to forget her.

Ch. V Dorrit complains about Amy to Mrs General because she is keeping the memory of the Marshalsea prison alive. He then cruelly reproaches Amy on entirely selfish grounds – to which Mrs General responds by offering tips on pronunciation. When Amy wishes to meet the Gowans, Tip reveals that they are friends of the Merdles. Dorrit sees this as a seal of approval – at which his brother Frederick suddenly erupts in protest against all this snobbery and money worship.

Ch. VI Fanny and Amy visit Gowan who is painting the portrait of Blandois. When Gowan’s dog takes a dislike to Blandois, Gowan kicks it into submission. On the way back, Fanny and Amy meet Sparkler who is besotted with Fanny. He is invited into the house and then in the evening to the opera, where Blandois reveals that the dog is now dead.

Ch. VII Fanny thinks Mrs General is setting her cap at her father. Sparkler is still in pursuit of Fanny. Henry Gowan grudgingly accepts a commission from Dorrit. Amy and her friend Minnie both dislike Blandois, who they think killed Gowan’s dog. There is a patronising visit from Mrs Merdle after which the family transfer to Rome.

Ch. VIII Clennam takes up Doyce’s patent application with the Circumlocution Office, ‘starting again from the beginning’. He is missing Little Dorrit and starting to feel that he is now too old for sentimental attachments. Dowager Mrs Gowan calls on the Meagles and patronises them regarding her son and his wife. She continues to maintain the fiction that they pursued her family.

Ch. IX The Meagles decided to go to Italy to look after Pet, who is expecting a baby. Henry Gowan has run up further debts. Clennam sees Tattycoram with Miss Wade and Blandois. He follows them to Casby’s house, but is delayed in a comic interlude by Flora and Mr F’s Aunt. When he asks Casby about Miss Wade he gets no information. However, Panks reveals that Casby holds money for Miss Wade, which she collects occasionally.

Ch. X Late one night Clennam meets Blandois going into his mother’s house, and wonders what the connection between them can be. Clennam protests his being there, but Mrs Clennam treats Blandois as a business contact. Flintwinch is summoned, and Mrs Clennam asks her son to leave whilst they conduct their business. Affrey Flintwinch cannot tell Clennam what is going on.

Ch. XI Little Dorrit writes to Clennam from Rome describing the Gowan’s poor lodgings and Pet’s being very much alone. Gowan is continuing his dissolute lifestyle, and yet his wife continues to be devoted to him. They now have an infant son. Sparkler has followed Fanny to Rome, and Little Dorrit herself feels homesick and keeps the memory of her former poverty alive.

Ch. XII Mr Merdle gives one of his lavish dinners which is attended by the Great and the Good. Powerful dignitaries regale each other with mind numbing anecdotes and jokes which are not funny. They agree to support the advancement of Sparkler, and are pleased to note his social connection with the now-wealthy Dorrit family. Merdle and Decimus Tite are brought together, after which it is announced that Sparkler is appointed to a high position in the Circumlocution Office.

Ch. XIII Panks calls on Mrs Plornish in her new shop (Happy Cottage) in Bleeding Heart Yard. Cavalletto is frightened after seeing Blandois in the street. Clennam calls by and invites Pancks to dinner. Pancks reveals that he has invested thousands in one of Merdle’s enterprises. Clennam obliquely tells Panks of his misgivings about his mother. Panks tempts him with easy money to be made from investments. He thinks he can’t lose because of Merdle’s immense capital and government connections.

Ch. XIV In Rome, Fanny feels trapped by her association with the gormless Sparkler, and is particularly resentful about being patronised by Mrs Merdle. She confides in Amy, but ends up engaged to be married to Sparkler.

Ch. XV Dorrit wishes Amy to announce his forthcoming marriage to Mrs General, but she refuses to do so. There is a stand-off between the two women. Fanny gets married then goes off with Sparkler and Dorrit to England, leaving Amy alone in Rome with Mrs General.

Ch. XVI Dorrit in London is visited by Merdle, who offers to ‘help’ him financially, now that they are connected by the marriage of their children. Dorrit basks in the glory of his association with the fabulously wealthy Merdle.

Ch. XVII Flora Casby visits Dorrit at his hotel, in quest of information about Blandois who has gone missing after visiting Clennam and Co. Dorrit visits Mrs Clennam that evening, but nobody has any additional information on Blandois. Further mysterious happenings are noted by Affrey Flintwinch.

Ch. XVIII Dorrit is visited by John Chivery, who he first abuses but then gives £100 for a treat to the Collegians. He then travels across France to Italy making plans and buying presents for Mrs General on the way.

Ch. XIX Dorrit arrives back in Rome late at night and is peeved to observe the close harmony between Little Dorrit and his brother Frederick. He insists that Frederick is ‘fading fast’ and begins paying court to Mrs General. However, it is Dorrit himself who is fading, and at a dinner given by Mrs Meagles he makes a speech believing he is back in the Marshalsea prison. Amy takes him back home, where he dies the same night.

Ch. XX Panks has located Miss Wade at an address in Calais, which Clennam visits, seeking information about Blandois. She reveals that she has employed him for some dubious purpose in Italy, but will tell Clennam nothing further. She produces Tattycoram, and they argue about her sentimental links with the Meagles family.

Ch. XXI Clennam reads a biographical note given to him by Miss Wade. In it she recounts her unhappy childhood as an orphan, and her perverse nature by which she spurns all offers of friendship and help. She forms passionate but conflicted attachments to both men and women, and feels a strong kinship with the cynic Henry Gowan.

Ch. XXII Doyce goes to work abroad, leaving Clennam in sole charge of their enterprise. They discuss the need for fiscal caution. Cavalletto recognises Blandois from Clennam’s description, and agrees to go in search of him.

Ch. XXIII Clennam is frustrated by his lack of information about Blandois. He visits his mother and appeals to her, but she refuses to help him or tell him anything. He also asks Affrey, but she is scared and merely refers to mysterious noises in the house and the recurrence what she calls her ‘dreams’.

Ch. XXIV Fanny is bored with her husband Sparkler. Her brother Edward (Tip) has sacked and paid off Mrs General following the death of his father (and uncle). They are visited by Mr Merdle who is in a rather strange state. He borrows a penknife before leaving them.

Ch. XXV Mrs Merdle attends a society party where rumours of a peerage for Mr Merdle are circulating. But the host is later called out when it is revealed that Merdle has committed suicide in the public baths. He has been exposed as a forger and a robber, and his bank collapses.

Ch. XXVI Clennam has invested everything with Merdle, and is now ruined. He is distraught about his responsibility towards his partner Doyce. He makes a public confession of his culpability, despite Mr Rugg advising him to be cautious and restrained. He is imprisoned in the Marshalsea, and is given Little Dorrit’s old room.

Ch. XXVII Young John Chivery battles with his feelings of rivalry whilst showering comforts on Clennam in the jail. He explains his discomfort in a comically ambiguous manner, but finally reveals to Clennam that Little Dorrit is in love with him. Clennam is puzzled and does not know what to do with this information.

Ch. XXVIII Clennam is visited in jail: first by Ferdinand Barnacle, who advises him to give up his struggles with the Circumlocution Office; next by Mr Rugg who wants him to enter into litigation; and finally by Blandois, who writes a letter to Mrs Clennam giving her a week to accept his ‘proposal’ – which is a threat of blackmail. Blandois taunts Clennam regarding his connections with Miss Wade and Mrs Gowan. Mrs Clennam agrees to meet Blandois in a week’s time.

Ch. XXIX Little Dorrit returns from Italy and visits Clennam in jail. She has come with her brother Edward who is enquiring into his father’s will. Amy offers Clennam all her money to release him from bankruptcy, but Clennam turns down her offer on very high-minded principal, and even advises her to stay away from him and the prison, and enjoy a better life for herself.

Ch. XXX Blandois visits Mrs Clennam, where Affrey finally rebels and refuses to obey Flintwinch’s commands. Blandois is threatening Mrs Clennam with information regarding the family’s secret history and the codicil to a will, all of which he has obtained from Flintwinch’s twin brother in Antwerp. He has also given copies of these compromising documents to Amy in the prison in a tightly controlled plot. It is also revealed that Mrs Clennam is not Arthur’s mother.

Ch. XXXI Mrs Clennam gets up from her wheelchair to dash to the prison, where she confesses the truth to Amy, who forgives her in saintly fashion. They dash back to the house to meet the deadline set by Blandois, but on arrival they find that the house has collapsed, killing him.

Ch. XXXII Clennam continues to be ill in jail. Casby bullies Panks, who finally rebels and resigns from his job as debt collector. He humiliates Casby by cutting off his hair in front of his tenants in Bleeding Heart Yard.

Ch. XXXIII Mr Meagles goes in search of the papers secured by Blandois. He asks Miss Wade in Calais, who denies all knowledge of them. But on his return to London Tattycoram brings him the original metal box and wishes to be reunited with the Meagles family. He passes the box over to Little Dorrit and goes off in search of Doyce.

Ch. XXXIV Little Dorrit once again offers to share her ‘entire fortune’ with Clennam, but he again refuses her offer, whereupon she reveals that she has no fortune – all her money disappeared in the Merdle collapse – and she confesses her profound love for him. Flora visits to recount her love for her ‘rival’ Amy, and Mr Meagles arrives with Doyce to take up his business again with Clennam, following which Clennam and Amy get married in a quiet ceremony.

Little Dorrit – principal characters

| John Baptist Cavalletto | a Genoese sailor and adventurer |

| Monsieur Rigaud (later Lagnier, then Blandois) | a bogus ‘gentleman’ and an assassin |

| Mr Meagles | a retired banker |

| Mrs Meagles | his wife |

| Minnie (Pet) | their pretty and pampered daughter (20) |

| Tattycoram (Harriet) | Pet’s conflicted maid, a foundling |

| Arthur Clennam | a gentleman and former businessman (40) |

| Mrs Clennam | his ‘mother’, a bitter and puritanical martyr |

| Jeremiah Flintwinch | her servant and later business partner |

| Affrey Flintwinch | his browbeaten and abused wife |

| Miss Wade | a strong-willed man-hater and orphan |

| William Dorrit | an elderly self-deluded debtor – the Father of the Marshalsea |

| Frederick Dorrit | his brother, a down-at-heel clarionet player |

| Amy (Little) Dorrit | William’s selfless and loyal daughter (20) |

| Fanny Dorrit | her sister – a dancer |

| Edward (‘Tip’) Dorrit | her feckless and wayward brother |

| Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle | controller of the Circumlocution Office |

| Clarence Barnacle | his son |

| Ferdinand Barnacle | his lacklustre son |

| Mr Plornish | a plasterer at Bleeding Heart Yard (30) |

| Sally Plornish | his wife |

| Maggy | Amy’s simple friend (28 – but mentally 10) |

| Daniel Doyce | an engineer and inventor |

| Christopher Casby | landlord of Bleeding Heart Yard |

| Flora Casby (Finching) | his daughter, Clennam’s old sweetheart, now a garrulous and feather-brained widow |

| Pancks | his nail-biting rent collector |

| Mr F’s Aunt | Flora’s ‘legacy’ from her late husband Finching |

| Henry Gowan | a talentless and cynical would-be ‘artist’ |

| John Chivery | Amy’s admirer, the prison lock-keeper’s son |

| Mrs Mary Chivery | a tobacco shop keeper |

| Mr Merdle | an unscrupulous and wealthy banker |

| Mrs Merdle | his vicious social-climbing wife |

| Edmund Sparkler | Mrs Merdle’s dim-witted son by her first husband |

| Mr Rugg | Pentonville debt collector and Panks’s landlord |

| Amastasia Rugg | his daughter, a husband-hunter |

| Lord Lancaster Stiltstalking | a retired Circumlocution Office official |

| Mrs Gowan | a snobbish elderly ‘Beauty’ |

| Mrs General | widow, governess to the Dorrits |

Charles Dickens – Further reading

Biography

![]() Peter Ackroyd, Dickens, London: Mandarin, 1991.

Peter Ackroyd, Dickens, London: Mandarin, 1991.

![]() John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens, Forgotten Books, 2009.

John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens, Forgotten Books, 2009.

![]() Edgar Johnson, Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph, Little Brown, 1952.

Edgar Johnson, Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph, Little Brown, 1952.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Dickens: A Biography, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Fred Kaplan, Dickens: A Biography, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

![]() Frederick G. Kitton, The Life of Charles Dickens: His Life, Writings and Personality, Lexden Publishing Limited, 2004.

Frederick G. Kitton, The Life of Charles Dickens: His Life, Writings and Personality, Lexden Publishing Limited, 2004.

![]() Michael Slater, Charles Dickens, Yale University Press, 2009.

Michael Slater, Charles Dickens, Yale University Press, 2009.

Criticism

![]() G.H. Ford, Dickens and His Readers, Norton, 1965.

G.H. Ford, Dickens and His Readers, Norton, 1965.

![]() P.A.W. Collins, Dickens and Crime, London: Palgrave, 1995.

P.A.W. Collins, Dickens and Crime, London: Palgrave, 1995.

![]() Philip Collins (ed), Dickens: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1982.

Philip Collins (ed), Dickens: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1982.

![]() Jenny Hartley, Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women, London: Methuen, 2009.

Jenny Hartley, Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women, London: Methuen, 2009.

![]() Andrew Sanders, Authors in Context: Charles Dickens, Oxford University Press, 2009.

Andrew Sanders, Authors in Context: Charles Dickens, Oxford University Press, 2009.

![]() Jeremy Tambling, Going Astray: Dickens and London, London: Longman, 2008.

Jeremy Tambling, Going Astray: Dickens and London, London: Longman, 2008.

![]() Donald Hawes, Who’s Who in Dickens, London: Routledge, 2001.

Donald Hawes, Who’s Who in Dickens, London: Routledge, 2001.

Other works by Charles Dickens

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

Charles Dickens – web links

![]() Charles Dickens at Mantex

Charles Dickens at Mantex

Biographical notes, book reviews, tutorials and study guides, free eTexts, videos, adaptations for cinema and television, further web links.

![]() Charles Dickens at Wikipedia

Charles Dickens at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary techniques, his influence and legacy, extensive bibliography, and further web links.

![]() Charles Dickens at Gutenberg

Charles Dickens at Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts of the major works in a variety of formats.

![]() Dickens on the Web

Dickens on the Web

Major jumpstation including plots and characters from the novels, illustrations, Dickens on film and in the theatre, maps, bibliographies, and links to other Dickens sites.

![]() The Dickens Page

The Dickens Page

Chronology, eTexts available, maps, filmography, letters, speeches, biographies, criticism, and a hyper-concordance.

![]() Charles Dickens at the Internet Movie Database

Charles Dickens at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of the major novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages

![]() A Charles Dickens Journal

A Charles Dickens Journal

An old HTML website with detailed year-by-year (and sometimes day-by-day) chronology of events, plus pictures.

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Dickens

Hyper-Concordance to Dickens

Locate any word or phrase in the major works – find that quotation or saying, in its original context.

![]() Dickens at the Victorian Web

Dickens at the Victorian Web

Biography, political and social history, themes, settings, book reviews, articles, essays, bibliographies, and related study resources.

![]() Charles Dickens – Gad’s Hill Place

Charles Dickens – Gad’s Hill Place

Something of an amateur fan site with ‘fun’ items such as quotes, greetings cards, quizzes, and even a crossword puzzle.

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on Charles Dickens

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Jim is a young English sailor fired with romantic dreams of heroism in the face of danger. On a sea voyage transporting pilgrims from Singapore to Jeddah in the Red Sea, his ship the Patna is involved in a collision. Thinking that the vessel is sinking, the crew (including Jim) abandon ship. However, the ship does not sink, but is rescued by a French boat and towed to safety. There is an official inquest into the incident in Bombay, before which the German captain absconds and at which Jim is stripped of his seaman’s certificate in dishonour.

Jim is a young English sailor fired with romantic dreams of heroism in the face of danger. On a sea voyage transporting pilgrims from Singapore to Jeddah in the Red Sea, his ship the Patna is involved in a collision. Thinking that the vessel is sinking, the crew (including Jim) abandon ship. However, the ship does not sink, but is rescued by a French boat and towed to safety. There is an official inquest into the incident in Bombay, before which the German captain absconds and at which Jim is stripped of his seaman’s certificate in dishonour. The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Chance

Chance Victory

Victory

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth