tutorial, commentary, and study resources

A New England Winter first appeared in magazine form in The Century Magazine for August—September 1884. It was then reprinted in book form amongst Tales of Three Cities in England and America in 1884. The setting for this tale is the New England capital of Boston, Massachusetts: the other two cities in the collection were New York and London.

A New England winter scene

A New England Winter – plot summary

Part I. Susan Daintry, a fastidious Boston widow, is awaiting a visit from her son Florimond, who has been studying art in Paris for six years. She is intensely concerned with the moral issues arising from microscopic niceties of protocols regarding her servant girl.

Part II. She visits her sister-in-law Lucretia, whose furnishings she inspects in a critical manner. The two women are subtly competitive with each other in terms of social ‘correctness’. Susan wants Lucretia to accept Rachel Torrence (Florimond’s cousin) as a lodger over the winter months in order to tempt him to stay at home – even though she would not wish Florimond to marry her. Lucretia thinks it would be wrong to make use of Rachel in this way.

Part III. In the days that follow however, both women change their minds, feeling that they have been in the wrong. Lucretia writes to Susan, offering alternative accommodation for Rachel. The letter crosses with a message from Susan apologising for having asked for the favour.

Part IV. When Florimond arrives at his mother’s house, he becomes increasingly critical of the disruption caused by his sister’s children. There are serious social protocols considered about the order of precedence in which people should visit each other. Florimond walks through a wintry Boston landscape to his aunt’s house.

Part V. Florimond egotistically tells his aunt all about his life in Paris, in an affected manner. She recommends that he meet Rachel, secretly hoping that the girl’s influence will challenge his pretensions, because Rachel is a spirited girl. Lucretia also secretly hopes that Florimond will fall in love with Rachel and be snubbed by her.

Part VI. Florimond becomes a habitué of a relative Mrs Pauline Mesh, and falls under the spell of Rachel, who becomes the celebrity of the winter season. He begins to see positives in Boston life and society. However, Mrs Mesh starts to tire of Rachel’s company. Susan Daintry arrives at Mrs Mesh’s house to find her son there, and feels guilty for what might be perceived as ‘spying’ on him. She is still in the dark regarding Florimond’s intentions. Rachel turns up and jousts verbally with Florimond. Later, his mother questions him about Rachel, but he is non-committal in his responses.

Part VII. Florimond increasingly appreciates the visual life of Boston, and travels to Cambridge. Lucretia worries about the relationship between Florimond and Rachel, but Rachel suddenly declares that she is due to go back to Brooklyn. She explains that she has been keeping Florimond occupied from a sense of duty whilst he is secretly enamoured of Pauline Mesh. Lucretia insists that Rachel come to stay with her.

Susan Daintry arrives at Lucretia’s with the stale news that Rachel is going back to New York – and all her winter’s worries are over. Lucretia reveals to her the latest true state of affairs. Florimond continues to visit Pauline Mesh’s house, and nothing changes – until Susan Daintry decides to go to Europe for the summer, and takes Florimond with her.

Principal characters

| Mrs Susan Daintry | a Boston widow |

| Beatrice | her servant |

| Florimon Daintry | a young impressionist painter who lives in Paris |

| Joanna Merriman | Susan’s daughter-in-law with six children |

| Miss Lucretia Daintry | Susan’s sister-in-law |

| Rachel Torrance | Florimond’s cousin, a poor would-be painter from New York |

| Mrs Pauline Mesh | a relative of the Daintry family from Baltimore |

Study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() A New England Winter – paperback edition – Amazon UK

A New England Winter – paperback edition – Amazon UK

![]() A New England Winter – paperback edition – Amazon US

A New England Winter – paperback edition – Amazon US

![]() A New England Winter – read the original publication

A New England Winter – read the original publication

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

A New England Winter – further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the gallant South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the gallant South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Chapter VII. At his next visit to the rectory, Stephen plays chess with Elfride, which he has taught himself from books. He has also learned Latin by post from his friend Mr Knight. Stephen tells Elfride that he loves her. They go together up onto the cliffs to continue their flirtations. They exchange their first kiss, she loses an ear ring, and they declare their love for each other. But Stephen suggests that there is something which will prevent their marrying.

Chapter VII. At his next visit to the rectory, Stephen plays chess with Elfride, which he has taught himself from books. He has also learned Latin by post from his friend Mr Knight. Stephen tells Elfride that he loves her. They go together up onto the cliffs to continue their flirtations. They exchange their first kiss, she loses an ear ring, and they declare their love for each other. But Stephen suggests that there is something which will prevent their marrying.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Lucy Honeychurch, a young upper middle class woman, visits Italy under the charge of her older cousin Charlotte. At their guesthouse, in Florence, they are given rooms that look into the courtyard rather than out over the river Arno. Mr. Emerson, a fellow guest, generously offers them the rooms belonging to himself and his son George. Lucy is an avid young pianist. Mr. Beebe an English clergyman guest, watches her passionate playing and predicts that someday she will live her life with as much gusto as she plays the piano.

Lucy Honeychurch, a young upper middle class woman, visits Italy under the charge of her older cousin Charlotte. At their guesthouse, in Florence, they are given rooms that look into the courtyard rather than out over the river Arno. Mr. Emerson, a fellow guest, generously offers them the rooms belonging to himself and his son George. Lucy is an avid young pianist. Mr. Beebe an English clergyman guest, watches her passionate playing and predicts that someday she will live her life with as much gusto as she plays the piano. Where Angels Fear to Tread

Where Angels Fear to Tread Howards End

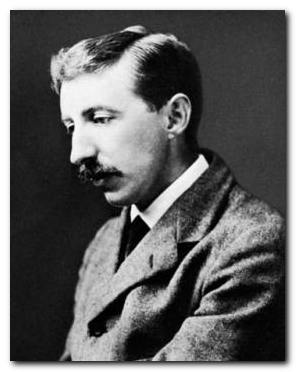

Howards End E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.

E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf