tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

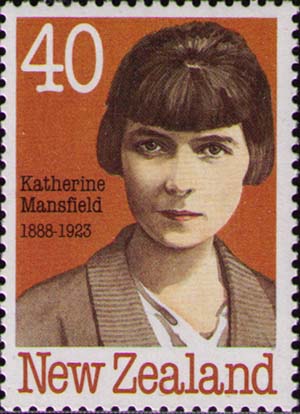

A Cup of Tea was written on 11 January 1922 in the space of just ‘4-5 hours’ and was published in a popular magazine the Story-teller in May of the same year. It then appeared in the collection The Dove’s Nest and Other Stories compiled by Katherine Mansfield’s husband John Middleton Murry and published in 1923.

A Cup of Tea – critical commentary

The ostensible point of the story is that a rich and self-regarding woman has her complacency disturbed. On a whim, she makes what she thinks of as a charitable gesture to a destitute lower-class girl, only to discover (via her husband) that the girl has qualities that she herself does not possess.

However, there is another reading of the story buried subtly in the narrative and its dialogue. Rosemary is a rich and spoiled woman with a self-indulgent lifestyle who feels that her sudden encounter with a girl off the streets could be ‘an adventure … like something out of a novel by Dostoevsky’ – which in a sense that Rosemary would not understand, it does turn out to be.

She takes the girl back home, ushers her into her private bedroom, and undresses her (in the sense of taking off her hat and coat). She has the intention of leading her into another room for tea but does not do so. When the girl begins to cry, she puts her arm around the girl’s ‘thin, bird-like shoulders’ and promises to look after her.

When Rosemary’s husband Philip interrupts, the young girl gives what is clearly a false name (‘Smith’) and is strangely unfazed by the situation in which she finds herself: she is ‘strangely still and unafraid’. Rosemary describes their encounter in terms of procurement: ‘I picked her up in Curzon Street. She’s a real pick-up’.

Philip, the husband, is shocked by two things – first, by how attractive the girl is, and second by the inappropriate relationship that exists between the two women. He asks satirically if ‘Miss Smith’ will be dining with them, in which case he might be forced to look up The Milliner’s Gazette.

The surface implication of this remark is that the girl might be an unemployed shop girl who is sponging off his wealthy wife, but at a deeper level there is a suggestion that she might be a prostitute of some kind. At that time in the early twentieth century, the employment of single females in occupations such as milliner (hat maker) shop assistant, and other forms of casual jobs was regarded as loosely equivalent to prostitution. This suggestion in the story is reinforced by what happens next. Rosemary pays off the girl with three pound notes and sends her on her way.

The sting in the tale for Rosemary is that she wonders if she, for all the wealth and luxury in her life, lacks the animal magnetism possessed by the lower-class young girl which has left her husband Philip ‘bowled over’ after a single glance.

Narrative voice

The literary quality in the story comes largely from the skillful manner in which Mansfield creates a fluid narrative voice which combines an engagement with her subject, her readers, and even (to some extent) with herself as an identifiable narrator.

Technically, the story starts in third person narrative mode: ‘Rosemary Fell was not exactly beautiful’ – but that ‘not exactly’ establishes a conversational style and an attitude to the character. She raises questions, cancels thoughts (‘No, not Peter—Michael’) employs slang (‘a duck of a boy’) and speaks to an imaginary interlocutor (‘she would go to Paris as you and I would go to Bond Street’).

It is also interesting to note that her use of fashionable exaggeration is remarkably similar to that being used today – almost a hundred years later: (‘her husband absolutely adored her … the man who kept it was ridiculously fond of serving her’). This captures perfectly the speech mannerisms and the attitudes of the nouveau riche milieu in which the story is set.

A Cup of Tea – study resources

Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Works

Three published collections of stories – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Collected Short Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Wordsworth Classics paperback edition – Amazon UK

The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Penguin Classics paperback edition – Amazon UK

Katherine Mansfield Megapack

The complete stories and poems in Kindle edition – Amazon UK

Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Works

Three published collections of stories – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Collected Short Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Wordsworth Classics paperback edition – Amazon US

The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Penguin Classics paperback edition – Amazon US

Katherine Mansfield Megapack

The complete stories and poems in Kindle edition – Amazon US

A Cup of Tea – plot summary

Rosemary Fell is a socially poised young woman who has been married for two years to a rich and devoted husband. She shops in the fashionable and expensive part of the West-End in London. An ingratiating antiques dealer shows her a small enamelled box which she covets but asks to be put by for her.

Coming out of the shop into the rain, she is accosted by a poor young woman who asks for the price of a cup of tea. Rosemary sees the incident as a potential adventure and invites the girl back home.

When they reach the house Rosemary takes the girl into her bedroom and relieves her of her hat and coat. The girl breaks down in tears and says she cannot go on any longer.

Rosemary gives the girl tea and sandwiches, whilst she herself smokes cigarettes. This relieves the girl, and they are about to start a conversation when they are interrupted by the arrival of Rosemary’s husband Philip.

Philip takes Rosemary into an adjoining room and asks her what is going on. She explains that she is merely trying to be kind to a poor girl. But Philip points out that the girl is remarkably pretty, but the relationship not desirable.

Rosemary gives the girl some money, and she leaves, after which Rosemary asks her husband if she can have the enamel box she has seen – but what she really wants to know from him is if she is pretty or not.

Katherine Mansfield – web links

Katherine Mansfield at Mantex

Life and works, biography, a close reading, and critical essays

Katherine Mansfield at Wikipedia

Biography, legacy, works, biographies, films and adaptations

Katherine Mansfield at Online Books

Collections of her short stories available at a variety of online sources

Not Under Forty

A charming collection of literary essays by Willa Cather, which includes a discussion of Katherine Mansfield.

Katherine Mansfield at Gutenberg

Free downloadable versions of her stories in a variety of digital formats

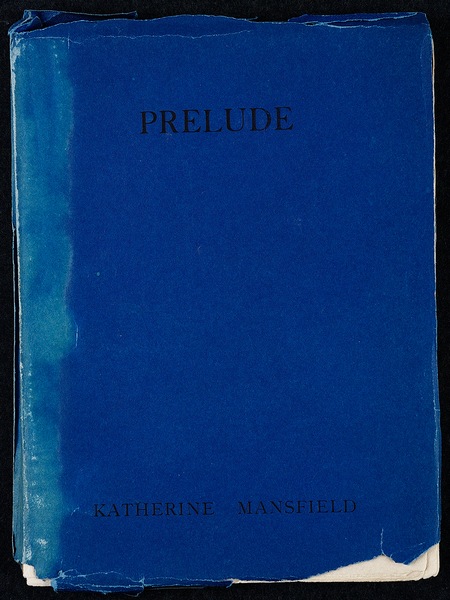

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, including Mansfield’s ‘Prelude’

Katherine Mansfield’s Modernist Aesthetic

An academic essay by Annie Pfeifer at Yale University’s Modernism Lab

The Katherine Mansfield Society

Newsletter, events, essay prize, resources, yearbook

Katherine Mansfield Birthplace

Biography, birthplace, links to essays, exhibitions

Katherine Mansfield Website

New biography, relationships, photographs, uncollected stories

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Katherine Mansfield

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on short stories

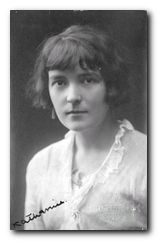

1888. Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp was born into a socially prominent family in Wellington, New Zealand. Her father was a banker, who went on to become chairman of the Bank of New Zealand. She was first cousin of Elizabeth Beauchamp, who married into German aristocracy to become Countess Elizabeth von Arnim. She had a somewhat insecure childhood. Her mother left her when she was only one year old to go on a trip to England. She was raised largely by her grandmother, who features in some of the stories as ‘Mrs Fairfield’.

1888. Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp was born into a socially prominent family in Wellington, New Zealand. Her father was a banker, who went on to become chairman of the Bank of New Zealand. She was first cousin of Elizabeth Beauchamp, who married into German aristocracy to become Countess Elizabeth von Arnim. She had a somewhat insecure childhood. Her mother left her when she was only one year old to go on a trip to England. She was raised largely by her grandmother, who features in some of the stories as ‘Mrs Fairfield’.

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield

Nadine Gordimer

Nadine Gordimer