tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

Madame de Mauves first appeared in The Galaxy magazine for February—March 1874. It was reprinted a year later as part of James’s first book, The Passionate Pilgrim and Other Tales, published by Osgood in Boston, 1875.

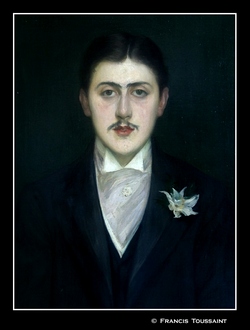

Saint-Germain in Spring – by Alfred Sisley

Madame de Mauves – critical commentary

This is an astonishingly mature work for such a young writer. James was only slightly over thirty years old at the time of the tale’s publication, and he had just come to the end of a ten year apprenticeship in writing reviews and short stories. He had yet to write any major work, but Madame de Mauves certainly points to his potential ability to do so. The theme of people entombed in unhappy relationships and solving their problems by renunciation is something he would explore in The Portrait of a Lady written only a few years later.

The international theme

As someone who had lived on both continents, James made the juxtaposition of America and Europe into one of his favourite subjects. Here the contrast is made between the two Americans Longmore and Euphemia de Mauves, and the Europeans (French) Count Richard de Mauves and his sister-in-law Madame Clarin.

Mauves belongs to an old aristocratic family which has no money. So he marries the wealthy Euphemia and reverts to family type by ignoring his marriage and indulging in petty affairs almost as a way of life. Madame Clarin explains all this to Longmore, including the fact that the family has a long tradition of suffering wives who have tolerated such behaviour for the sake of the family’s ‘name’ in society.

Count Mauves has noticed Longmore’s interest in his wife, and encourages his attentions, hoping that the two of them will begin an affair which will in its turn justify his own way of life. To contemporary readers this might seem like an improbably melodramatic plot device, but in fact it is based on the historically sound observation that amongst the upper classes, sexual fidelity has never been a high priority.

So long as the appearance of propriety was maintained and no scandal allowed to sully a family’s name (a collective responsibility) adulteries of all kinds could be incorporated into the practices of upper-class life. Husbands did not have to give any reasons for being absent from their families. Wives could amuse themselves with any number of married or single men (as Euphemia does with Longmore).

The prime objective was to consolidate the family unit as a symbol of accumulated capital and property – which is why Count Mauves’ eventual suicide has been criticised by some commentators as somewhat improbable. There is no reason why he should not merely revert to his previous adulteries and keep the family and its name intact and unsullied.

Of course all this throws French society into a very dubious light compared with the upright behaviour of the two principal Americans. Longmore and Euphemia clearly love each other, but she manages to persuade him to adopt the honourable route of renunciation and self-denial. Madame Clarin on the other hand offers Longmore a ‘devil’s pact’ argument that the family traditions provide an open pathway to socially sanctioned adultery. The two Americans take the honourable way out, at the expense of their own personal happiness.

Madame de Mauves – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1874—1884 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1874—1884 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1874—1884 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1874—1884 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() Madame de Mauves – eBook formats at Gutenberg

Madame de Mauves – eBook formats at Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Madame de Mauves – plot summary

Part I. Rich American Longmore has been in Saint Germain for six months when his fellow American acquaintance Mrs Draper introduces him to Madame Euphemia de Mauves. She is a rich American woman married to a Frenchman who is intent on spending all her money. She is domestically unhappy, and Mrs Draper encourages Longmore to ‘entertain’ her.

Part II. Euphemia has been educated in a convent and has generated a romantic ambition to marry an aristocrat. Her childhood friend Marie de Mauves invites her to the ancestral home in the Auvergne, where old Madame de Mauves advises her to ignore moral niceties and act pragmatically.

When Richard de Mauves arrives, Euphemia sees him as the epitome of an aristocratic gentleman – although he is in fact a wastrel with unpaid bills. When he proposes marriage, Euphemia is very happy. But her mother imposes a two-year ban on the relationship – but at the end of it she marries him.

Part III. Longmore visits Madame de Mauves and marvels at her resignation. Euphemia’s sister-in-law is married to a wholesale pharmacist who gambles and loses on the stock exchange, then commits suicide. The widow pays court to Longmore, who dislikes her.

He ought to join his old friend Webster in Brussels for a holiday, but feels obliged to ‘support’ Madame de Mauves in her unhappiness. Her husband absents himself from the family home, but is amazingly polite to Longmore and encourages him to keep visiting.

Part IV. Webster writes to Longmore, asking about their planned holiday. Longmore asks Euphemia if she is happy or not – and she tells him it is an entirely private matter, and encourages him to join his friend on holiday. As he takes his leave he is patronised by the Count. Longmore writes to his friend Mrs Draper with his assessment of Madame de Mauves and her husband.

Part V. Longmore goes to Paris, but instead of going on to Brussels, he lingers there, thinking about Madame de Mauves and wondering if he is in love with her or not. Whilst dining in the Bois de Boulogne he sees the Count with a woman of the streets. He returns immediately to Saint Germain where he and Madame de Mauves discuss her situation and his wish to ‘support’ her – during which the Count casually passes by. Longmore is teased and patronised by Madame Clarin.

Part VI.When Longmore next visits the house, Madame de Clarin recounts to him the family history of faithless husbands and long-suffering wives. She also reveals that because the Count’s latest ‘folly’ has been discovered, he has suggested to his wife that she take Longmore as her lover, to form a social quid pro quo.

Part VII. Longmore takes a bucolic interlude in which he meets a young artist and his lover at a country inn, then falls asleep in the forest and dreams of being separated from Madame de Mauves by her husband.

Part VIII. When Longmore next meets Madame de Mauves she wants him to make a big sacrifice for both of them (by renouncing her) – so that she can continue to have someone to look up to and respect.

Part IX. Lomgmore is deeply conflicted on the issue, and he wonders why Euphemia should be so self-denying and stoical. He retreats to Paris to think about his decision. Once again he bumps into the Count in a compromising situation. Longmore leaves Saint Germain, and the Count is severely discomfited.

Part X. Two years pass, then Longmore learns from Mrs Draper that the Count repented and begged to be re-accepted by Madame de Mauves. She refused to accept him, so he committed suicide. Longmore returns to America and remains there.

Principal characters

| Longmore | a rich young man from New York |

| Mrs Maggie Draper | his American friend in England |

| Madame Euphemia de Mauves | a rich American (née Cleve) |

| Count Richard de Mauves | her philandering husband |

| Marie de Mauves | Euphenia’s young friend |

| old Madame de Mauves | Marie’s grandmother |

| Mrs Cleve | Euphenia’s mother |

| Madame Clarin | Euphemia’s sister-in-law |

| M. Clarin | wholesale druggist and gambler |

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Henry James – web links

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

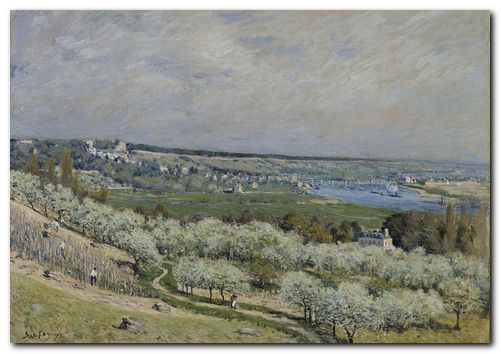

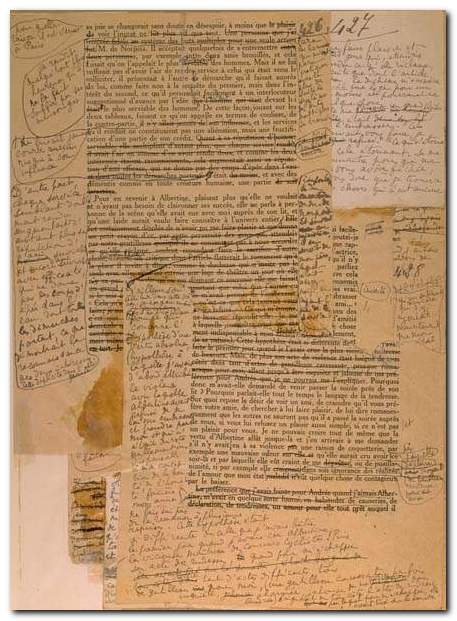

Most English-speaking readers will choose to read Marcel Proust in translation. And his literary style is quite demanding. His sentences are long, the paragraphs are huge, and his great novel is one of the longest ever – at a million and a half words. But the effort is worthwhile – and the benefits are enormous. Proust offers gems of psychological perception on every page, and his characters come alive in a way which makes you feel they become your personal friends. There is very little in the way of plot, suspense, or even story in a conventional sense. This modern classic is one which depicts an entire world of upper-class fin de siècle French characters circling round each other before and shortly after the First World War.

Most English-speaking readers will choose to read Marcel Proust in translation. And his literary style is quite demanding. His sentences are long, the paragraphs are huge, and his great novel is one of the longest ever – at a million and a half words. But the effort is worthwhile – and the benefits are enormous. Proust offers gems of psychological perception on every page, and his characters come alive in a way which makes you feel they become your personal friends. There is very little in the way of plot, suspense, or even story in a conventional sense. This modern classic is one which depicts an entire world of upper-class fin de siècle French characters circling round each other before and shortly after the First World War.

The second option

The second option The most recent

The most recent The Cambridge Companion to Proust

The Cambridge Companion to Proust