amusing character sketches, fictions, and memoirs

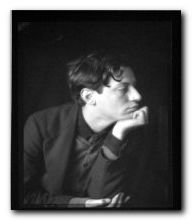

Harold Nicolson was a career diplomat, best known for the fact that he was married to Vita Sackville-West, who had a love affair with Virginia Woolf (and other women) and that despite his own homosexuality they kept going a marriage whose apparent success was recorded in their son’s account, Portrait of a Marriage. Nicolson blew this way and that in both literary and sexual terms, but in 1927 he produced a wonderful collection of portraits, Some People, which is part documentary and part fiction.

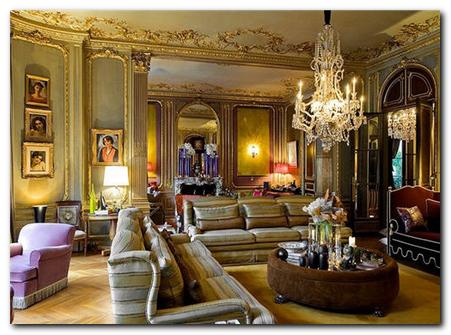

They are based on his experiences of public school and the diplomatic service. The idea he explained to a friend ‘was to put real people into imaginary situations, and imaginary people into real situations’. You can view this as a new literary form, alongside such works as Virginia Woolf’s Orlando or just a personal whim, but the result is surprisingly polished and amusing. The sketches are based upon just the sort of upper-class privileged life Nicolson had led – scenes of a childhood spent in foreign legations supervised by a governess; life as a boarder at Wellington College; and early postings amongst similar toffs at the Foreign Office.

They are based on his experiences of public school and the diplomatic service. The idea he explained to a friend ‘was to put real people into imaginary situations, and imaginary people into real situations’. You can view this as a new literary form, alongside such works as Virginia Woolf’s Orlando or just a personal whim, but the result is surprisingly polished and amusing. The sketches are based upon just the sort of upper-class privileged life Nicolson had led – scenes of a childhood spent in foreign legations supervised by a governess; life as a boarder at Wellington College; and early postings amongst similar toffs at the Foreign Office.

In one story Nicolson accompanies Lord Curzon on a diplomatic peace mission to Lausanne where he is due to negotiate with Poincaré and Mussolini – but the whole of the tale is focused on the Dickensian figure of Lord Curzon’s valet who drinks too much and disgraces himself in comic fashion at a high-ranking gala.

The stories are written in the first person – and for someone who had the opinions for which Nicolson became infamous, they are refreshingly self-deprecating. The narrator is more often than not the character in the wrong, the person who has a lesson to learn from others or from life itself. Real people such as Nicolson himself, Marcel Proust, Princess Bibesco, and Winston Churchill flit amongst fictional constructions in a perfectly natural and convincing manner.

The world of public school and Oxbridge run straight through seamlessly into that of the diplomatic service, and even though Nicolson’s conclusions are that its stiff conventions should be challenged and even broken, his stories rest heavily on the shared values of the Old School Tie, letters of introduction, and the right accent.

They reminded me of no less than the early stories of Vladimir Nabokov (written around the same time) which similarly combine autobiographical memoirs with fictional inventions. And the style is similar – supple, fast-moving sentences, a fascination with foreign words and places, and the phenomena of everyday life pinned down with well-observed details.

There was a lake in front of the hotel, cupped among descending pines, and in the middle of the lake a little naked island, naked but for a tin pagoda, with two blue boats attached to a landing-stage of which the handrail was of brown wood and the supports of pink.

It was this that made me think again of Jeanne de Hénaut.

It is writing which is very sophisticated, and which ultimately flatters the reader – it draws you seductively into this world of privilege, clubishness, and money. And yet if he had written more, I should certainly want to read them.

© Roy Johnson 2001

Harold Nicolson, Some People, London: Constable, 1996, pp.184, ISBN: 094765901

More on Harold Nicolson

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

More on short stories

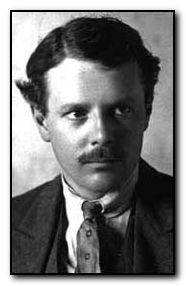

T.S.Eliot (Thomas Stearns) was born in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1888. His father was a successful businessman, and his mother wrote poems. From 1898 to 1905 he attended Smith Academy where he studied French, German, Latin, and Ancient Greek. At the age of fourteen he began to write poetry, heavily under the influence of The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam which enjoyed a vogue around that time. He published his first poem in the Smith Academy Record when he was fifteen.

T.S.Eliot (Thomas Stearns) was born in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1888. His father was a successful businessman, and his mother wrote poems. From 1898 to 1905 he attended Smith Academy where he studied French, German, Latin, and Ancient Greek. At the age of fourteen he began to write poetry, heavily under the influence of The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam which enjoyed a vogue around that time. He published his first poem in the Smith Academy Record when he was fifteen.

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

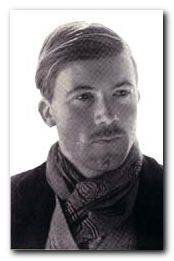

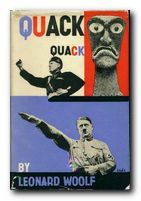

Almost without exception, the members of the Bloomsbury Group were opposed to the first world war. Their attitudes varied from outright pacifism through conscientious objection to quietism and a form of radical internationalism normally only found in figures such as Trotsky and Lenin. The origins of these attitudes – which were extremely unusual at the time – lay in the liberal, laissez-faire, free-thinking and non-religious beliefs which seemed to have spread from late nineteenth-century intellectuals such as

Almost without exception, the members of the Bloomsbury Group were opposed to the first world war. Their attitudes varied from outright pacifism through conscientious objection to quietism and a form of radical internationalism normally only found in figures such as Trotsky and Lenin. The origins of these attitudes – which were extremely unusual at the time – lay in the liberal, laissez-faire, free-thinking and non-religious beliefs which seemed to have spread from late nineteenth-century intellectuals such as

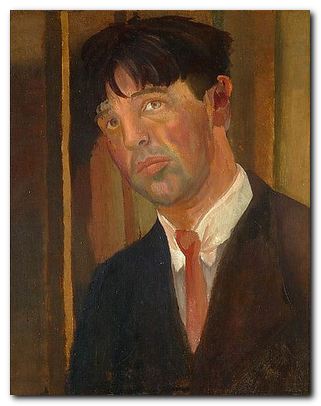

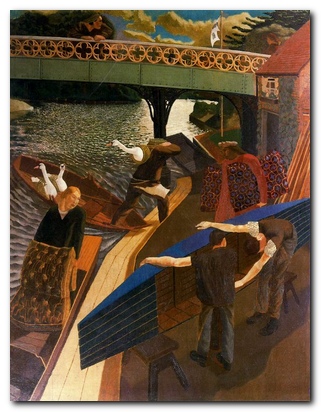

The painter

The painter