tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

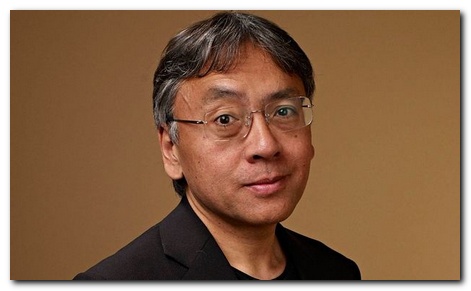

More Die of Heartbreak (1987) comes in the middle of Saul Bellow’s mature period as a novelist. He had won the Nobel Prize for Literature in the previous decade, and obviously felt confident as the chronicler of modern American society. However, he continued to keep alive the folk memories of his heritage as the son of Jewish immigrants and his connections with European society from which his grandparents had emigrated.

The novel features many of his characteristic tropes and character types – corrupt lawyers, businessmen, and politicians; the violence of modern urban centres; rapacious females; and the dominance of the metropolitan city in contemporary American life.

More Die of Heartbreak – commentary

Saul Bellow’s novels very often feature a central character who is trying to make sense of the world in which he lives. These protagonists can be slightly tragic figures such as Tommy Wilhelm in the novella Seize the Day (1956) or the comic Moses Herzog who writes letters to dead philosophers in Herzog (1964).

Frequently the central character or narrator will be presenting a second larger-than-life character who is being held up as a role model of some kind. Humboldt’s Gift (1975) is narrated by Charlie Citrine, but it is the figure of his friend Humbolt Fleischer who provides a great deal of the novel’s amusement and interest. Bellow does the same thing: in Ravelstein (2000) where the narrator Chick is searching for meaning, but the novel is dominated by the portrait of his colleague Abe Ravelstein.

More Die of Heartbreak follows the same pattern – but in surprisingly muted tones. Neither the narrator Kenneth Trachtenberg nor his uncle Benn Crader are large scale comic figures, and they are beset by no more serious problems than entanglements with the opposite sex.

Benn Crader is supposed to be a world-class botanist – but this characterisation is never fully persuasive, just as Kenneth Trachtenberg’s role as a professor of Russian literature is not convincingly realised. We simply do not see these characters at work sufficiently to give them full fictional credibility. Moreover, there is never sufficiently persuasive evidence provided for Ken’s obsessive interest in his older uncle’s welfare.

The main theme

Kenneth is surrounded by conflicting influences and role models. His father is a successful playboy, and his mother has turned herself into a Saint Theresa missionary figure in response. Ken admires his uncle Benn, and he has other relatives who include a corrupt politician who has swindled his own family.

Ken sustains himself in this social maelstrom by his belief in the humanising influence of his academic discipline – Russian literature. He also employs what is now called cultural history as a lodestone as he finds himself dragged into more and more complex entanglements generated by modern American life.

There is also a surprisingly understated element of his being trapped between the position of an insider and outsider. He is from a Jewish immigrant family, but was born and raised in France. He keeps modern European history firmly in mind – the Russian revolution, the Nazi death camps – as he tries to steer his uncle Benn through American waters infested by legal sharks and property speculators. All of this will be familiar territory to those acquainted with Bellow’s other major novels.

The secondary theme

However, a secondary or sub-theme emerges from just about every part of the novel’s events – and that is a surprisingly explicit interest in sexuality. It should also be said that although it is articulated via Ken as the narrator, this almost obsessive interest must be attributed to Saul Bellow. He depicts a world shot through with an almost obsessional interest in sexuality at every level.

This begins with the slightly unpleasant and barely credible interest Ken takes in his uncle Benn’s sex life following the breakdown of his marriage. The idea of two adult males from different generations sharing erotic technique tips is as aesthetically toe-curling as it is improbable.

Ken also gives full accounts of his father’s adulterous sexual activities – which are not only successful, but are endorsed by Ken and tolerated by his wife. Ken himself is involved with Trekkie, a young woman whom he suspects of being engaged in sado-masochistic practices with other men which leave her with bruises on her legs.

Benn is being vigorously pursued by the rapacious cougar Caroline Bunge, who spices up her sexual attractions with pornographic videos and drugs. And when Benn courteously changes a light bulb for a lonely neighbour, she pursues him saying “What am I supposed to do with my sexuality?”

When Ken and Benn make a sudden trip to Japan, the outstanding element of the visit is not Benn’s lectures on plant biology but a visit to a strip club which culminates in two girls displaying their vaginas to the crowd. Later, when Benn meets his prospective father-in-law Doctor Layamon, the gynaecologist’s principal topic of interest is the sexual relationship Benn has with his daughter Matilda.

Every one of these incidents can be justified on grounds of narrative relevance and the context of post sexual revolution writing in the 1980s. But responsibility for their volume and insistence lies clearly at Saul Bellow’s own door. It leaves behind a slightly unpleasant impression.

It is not easy to take seriously a concern for the victims of Stalin’s show trials and Hitler’s death camps, with a prurient interest in the bedroom positions and practices of a middle-aged couple during copulation. But it seems that these contrasting or even contradictory issues are precisely what Saul Bellow wishes to present as the challenge of modern consciousness.

The Flight from Woman

The other side of this coin of sexual obsession is the theme of escaping from the clutches of rapacious women. At the start of the novel Ken is in flight from Trekkie – a woman to whom he is sexually attracted but regards as perverse, since she seems to be engaged in sado-masochistic behaviour with other lower-class men.

Uncle Benn on the other hand is being pursued by Caroline Bunge, from whom he escapes on the very day they are due to be married. He then falls into the clutches of the ambitious Matilda Layamon, who is part of a rich and successful family. However, they wish to use Benn as a status-gainer on their social circuit. Benn marries Matilda – but shortly afterwards escapes from her and flies off to the ‘North pole’ to join a research project.

The logic of the narrative is that women are attractive and desirable as sexual partners, but that socially they are demanding, expensive, and uncontrollable. It is significant that Ken finds his only relaxing connection with Dita Schwartz, who has been virtually de-sexualised as a result of a horrendous dermatological operation on her face.

The setting

It is quite clear from the incidental details that the novel is set imaginatively in Chicago. Yet Bellow for some reason avoids a specific location for the events of the narrative. The main focus of attention is on the fictional ‘Radio Tower’ – which is fairly obviously the mammoth Willis Tower in Chicago

Straight ahead of us stood the Electronic Tower, with its twin masts like the horns of a Viking helmet – it was very nearly as tall as the Sears building in Chicago.

This is something of a literary joke, because the giant Willis Tower in Chicago is commonly referred to as the Sears Tower. But why should Bellow adopt this sleight of hand? Maybe because in other parts of the novel he is exposing all sorts of corrupt practices in the legal and political life of what is obviously Chicago. He gives himself a certain protection by the creation of a fictional city – which is never named.

The conclusion

Saul Bellow’s novels are unusual in that their narratives rarely culminate in a dramatic finale or even a resolution to the conflicts they have been exploring. More Die of Heartbreak concludes with Benn Crader running away from his unsuitable wife to pursue his scientific interests in a remote place. The narrator Kenneth Trachtenberg remains where he was at the beginning of the novel – a teacher of Russian literature who might have occasional custody of his daughter.

They both seem to have undergone a certain amount of erotic-based heartache, and they have theorised about their attitudes to women ad nauseam. There is a sense in which Bellow’s novels do not offer dramatic narratives: they explore states of mind and a portfolio of contemporary beliefs. Nor do they offer any comforting certainties or resolutions: there is very little sense of closure here.

More Die of Heartbreak – study resources

![]() More Die of Heartbreak – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

More Die of Heartbreak – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() More Die of Heartbreak – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

More Die of Heartbreak – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() More Die of Heartbreak – Library of America – Amazon UK

More Die of Heartbreak – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() More Die of Heartbreak – Library of America – Amazon US

More Die of Heartbreak – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() Saul Bellow – Collected Stories – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Saul Bellow – Collected Stories – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Saul; Bellow – Collected Stories – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Saul; Bellow – Collected Stories – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Saul Bellow (Modern Critical Views) – essays and studies – Amz UK

Saul Bellow (Modern Critical Views) – essays and studies – Amz UK

![]() Saul Bellow (Modern Critical Views) – essays and studies – Amz US

Saul Bellow (Modern Critical Views) – essays and studies – Amz US

Cambridge Companion to Saul Bellow – Amazon UK

More Die of Heartbreak – synopsis

Young professor of Russian literature Kenneth Trachtenberg gives an account of his uncle Benn Crader, a Jewish botanist who has recently become divorced. Ken also describes his ambivalent relationship with his womanising father Rudi, who is disappointed with his son’s lack of ambition and panache.

Ken’s relative Harold Vilitzer is a crooked politician who has defrauded his own family, yet Benn still feels an affection for him. Ken wonders why his uncle has chosen botany as a vocation, and he tries to generate a coherent understanding of life from his disparate collection of relatives.

Ken has problems with his partner Trekkie, who refuses to marry him, lives like a student even though she has money, and has a taste for sexual masochism. Benn is being pursued by Caroline Burge, a rich and fast-living vamp with a taste for drugs and celebrities. Ken and Benn take a holiday in Japan to escape from these problems on the day Benn is due to get married.

Ken has visited his mother who is working in a Somalian refugee camp. She too is disappointed in her son. He talks to her about the Gulag archipelago and Russia’s talent for suffering. In Kyoto Benn finds a visit to a strip club rather upsetting.

Without telling Ken during his absence, Benn marries Matilda Layamon, a rich young woman with a celebrity doctor father. Ken disapproves of his choice and is severely critical of the Layamons’ vulgar ostentation. Benn moves into the Layamons’ appartments, and Matilda is revealed as a spoiled and ambitious dilettante socialite. Doctor Layamon’s wealth is founded on dubious favours from his rich clients.

Benn and Matilda look over the enormous apartment she has inherited. Layamon takes Benn to an expensive lunch where he reveals that he has had Benn investigated by a private detective. He also wants Benn to recover the money Vilitzer owes him to pay for the refurbishment of the old apartment.

Ken pumps the seedy entrepreneur Fishl Vilitzer for information about his father. and judge Amador Chetnick. Fishl wants to act on Benn’s behalf in an effort to retrieve the money he lost in the rigged court case. Fishl explains the financial and political corruption in local government – but obviously has mixed motives.

Ken looks after his ex-student Dita Schwartz who has drastic dermatological surgery on her face. He meets Trekkie’s mother – who suddenly proposes marriage to him.

Dr Layamon takes Benn on hospital rounds, then persuades him to challenge Vilitzer for the money he owes. Benn and Matilda see Psycho which upsets him because he identifies with Norman Bates. He regards this as a warning, but marries her anyway.

Ken has dinner with Dita Schwartz and lectures her about his Parisian childhood. Ken and Benn attend the rape case parole board hearing They confront Vilitzer, but he refuses to give them the money he has made from the family property.

Ken flies to Seattle, bent on ‘revenge’ He smashes up Trekkie’s bathroom, then they discuss sharing custody of their daughter Nancy. Benn flies to Miami, where Vilitzer has just died. He then tricks Matilda into flying on to Rio, whilst he jets off instead to northern Finland on an arctic research expedition.

More Die of Heartbreak – principal characters

| Kenneth Trachtenberg | the narrator, a Jewish professor of Russian literature who was born in France |

| Benn Crader | a midwestern botanist of Jewish origins with an international reputation |

| Rudi Trachtenberg | Ken”s father, a successful womaniser |

| Matilda Layamon | Benn’s rich and attractive second wife |

| Harold Vilitzer | a crooked politician who has cheated his own family |

| Fishl Vilitzer | his son, a seedy and incompetent ‘entrepreneur’ |

| Treckie | Ken’s partner, who refused to marry him |

| Tanya Sterling | Trekkie’s mother – a cougar |

© Roy Johnson 2017

More on Saul Bellow

More on the novella

More on short stories

Twentieth century literature

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Eugene Onegin

Eugene Onegin A Hero of Our Time

A Hero of Our Time Dead Souls

Dead Souls Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground

From the House of the Dead

From the House of the Dead Crime and Punishment

Crime and Punishment The Brothers Karamazov

The Brothers Karamazov  Anna Karennina

Anna Karennina War and Peace

War and Peace Fathers and Sons

Fathers and Sons

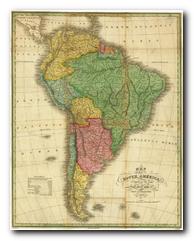

The location of the novel is Costaguana, a fictional country on the western seaboard of South America, and the focus of events is in its capital Sulaco, where a silver mine has been inherited by English-born Charles Gould but is controlled by American capitalists in San Francisco. Competing military factions plunge the country in a state of civil war, and Gould tries desperately to keep the mine working. Amidst political chaos, he dispatches a huge consignment of silver, putting it into the hands of the eponymous hero, the incorruptible Capataz de Cargadores, Nostromo.

The location of the novel is Costaguana, a fictional country on the western seaboard of South America, and the focus of events is in its capital Sulaco, where a silver mine has been inherited by English-born Charles Gould but is controlled by American capitalists in San Francisco. Competing military factions plunge the country in a state of civil war, and Gould tries desperately to keep the mine working. Amidst political chaos, he dispatches a huge consignment of silver, putting it into the hands of the eponymous hero, the incorruptible Capataz de Cargadores, Nostromo. A great deal of the narrative tension in this long novel turns on who knows what about whom, and many of the key scenes are drenched in dramatic irony built on coincidences which have all the improbability of the nineteenth century novel hanging about them. At one point a completely new character suddenly appears as a stowaway on a boat, and then improbably survives a collision with another ship in the dark by hanging onto the other boat’s anchor. And this is merely a plot device allowing him to transmit misleading information to his captors – and incidentally allows Conrad to indulge in a rather unpleasant bout of anti-semitism.

A great deal of the narrative tension in this long novel turns on who knows what about whom, and many of the key scenes are drenched in dramatic irony built on coincidences which have all the improbability of the nineteenth century novel hanging about them. At one point a completely new character suddenly appears as a stowaway on a boat, and then improbably survives a collision with another ship in the dark by hanging onto the other boat’s anchor. And this is merely a plot device allowing him to transmit misleading information to his captors – and incidentally allows Conrad to indulge in a rather unpleasant bout of anti-semitism.

Nostromo is an Italian expatriate who has risen to that position through his daring exploits. (‘Nostromo’ is Italian for mate or boatswain, as well as a contraction of nostro uomo – ‘our man’.) He is so named by his employer, Captain Mitchell. Nostromo’s real name is Giovanni Battista Fidanza – Fidanza meaning ‘trust’ in archaic Italian. Nostromo is what would today be called a shameless self-publicist. He is believed by Señor Gould to be incorruptible, and for this reason is entrusted with hiding the silver from the revolutionaries. He accepts the mission not out of loyalty to Señor Gould, but rather because he sees an opportunity to increase his own fame.

Nostromo is an Italian expatriate who has risen to that position through his daring exploits. (‘Nostromo’ is Italian for mate or boatswain, as well as a contraction of nostro uomo – ‘our man’.) He is so named by his employer, Captain Mitchell. Nostromo’s real name is Giovanni Battista Fidanza – Fidanza meaning ‘trust’ in archaic Italian. Nostromo is what would today be called a shameless self-publicist. He is believed by Señor Gould to be incorruptible, and for this reason is entrusted with hiding the silver from the revolutionaries. He accepts the mission not out of loyalty to Señor Gould, but rather because he sees an opportunity to increase his own fame.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended. The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes