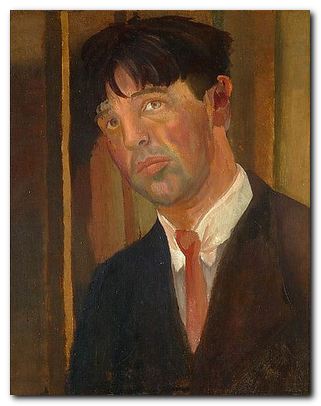

visionary English modernist painter

Stanley Spencer (1891-1959) was an English painter from the early modernist period. He was the youngest child of a large middle-class artistic family who lived in Cookham, a small village on the Thames. The cultural ambiance in the household was one of music and church-going. Spencer had very little formal education, since his father had snobbish doubts about the local council school, but could not afford the fees for a private education. He ran his own private school in a shed in next door’s garden.

Spencer’s talent for drawing was encouraged by the wife of the local landowner. She suggested the Slade School of Art (where she had studied herself) and he was admitted and at his father’s insistence that he should not be subjected to any examinations, was allowed to bypass the written entrance requirements. He studied under Wilson Steer and the formidable Henry Tonks, and he was a contemporary of Mark Gertler, Richard ‘Chips’ Nevinson, Isaac Rosenberg, Dora Carrington, and David Bomberg.

Being small, wearing glasses, and having the general appearance of a young boy, it was not surprising that he became something of a scapegoat and the butt of jokes amongst his fellow students, many of whom developed a life style that combined upper class raffishness with what we now think of as art school bohemianism. Nevinson called him ‘Cookham’, the village to which he travelled home by train every day. It was a nickname which stuck with him for the rest of his days at the Slade.

By the end of his first year Spencer had won a scholarship prize – though it was initially withheld from him on the technical objection that he had not taken the initial written entrance examination. Although he received very little instruction in painting whilst at the Slade, around this time he began to produce his now famous paintings of everyday life in Cookham village that also included religious figures and scenes from the bible (Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem).

Unlike some of his contemporaries at the Slade, he was not touched by the fashionable influences of the post-Impressionists, but continued painting in the same style as he had always done – a combination of realistic depiction with visionary subject matter. He also steered clear of all the intellectualising and theorising about the nature of Art that was rife amongst his fellow artists.

By 1912 he had twice won Slade prizes despite the fact that sometimes he had to work on the kitchen table at home, surrounded by his parents and brothers and sisters. He left the Slade in the same year, but was included in the second Grafton Gallery exhibition of post-Impressionists, alongside works by Picasso, Matisse, and Cezanne. Even though he behaved like a bucolic recluse, his work became sought after by collectors such as Eddie Marsh and Lady Ottoline Morrell, who bought his works both for her own collection and on behalf of the Contemporary Arts Society.

At the outset of war in 1914 he felt ambivalent about enlisting, but eventually joined the medical service and was posted to a recovery unit in an old lunatic asylum just outside Bristol. He hated the long hours, the drudgery, and the military discipline – but whilst there his painting The Centurion’s Servant caused a stir at the London Group exhibition in November 1915. He then volunteered for an overseas expeditionary posting, and was sent to Macedonia, which he found strangely exciting and exotic.

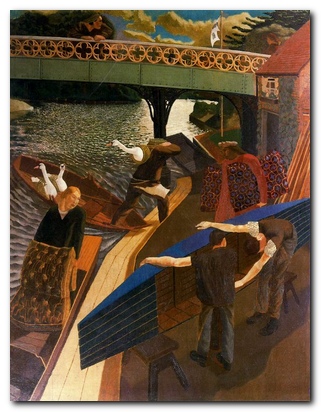

Spencer was pinned down in the Balkans whilst suffering from the irony that he had been asked to contribute to a war memorial. When the conflict finally ended he was given rapid transit back home – only to find that plans for the memorial had meanwhile been scrapped. However, he threw himself into the completion of one of his masterpieces, Swan Upping at Cookham which had been left unfinished at his conscription.

In 1925 his life changed quite dramatically. First he suddenly married a fellow Slade student Hilda Carline and he discovered a new subject for some of his later works – conjugal sex. The sudden change to his normally puritanical lifestyle presaged major disruptions. He moved back to live in Cookham trying (unsuccessfully) to recapture some of his earlier feelings and artistic inspiration. Then he met Patricia Preece, another former Slade student who was living in the village with her lover Dorothy Hepworth.

Spencer became obsessed with Patricia and eventually proposed a menage a trois with his wife Hilda, but she refused and divorced him. He immediately married Patricia who as a lesbian equally refused to consummate their marriage or even live in the same house. However, since she controlled his finances, when he signed over the deeds of his own home to her, his new wife forced him out, so he ended up with a wife, an ex-wife, and two children to support. Perhaps not surprisingly he had a nervous breakdown.

This period was also the source of one of his most controversial paintings – the Leg of Mutton Nude or to give the work its more correct title Double Nude Portrait: The Artist and His Second Wife (1937). This is an overtly sexual (though not erotic) portrait of Spencer and Patricia, with a joint of lamb in the foreground. It was never exhibited in his lifetime. Later, the outgoing president of the Royal Academy, Sir Alfred Munnings initiated a police prosecution against Spencer for obscenity. The irony in all this is that the portrait shows the bespectacled Stanley looking down longingly on the naked body of Patricia, the wife with whom he never had sex.

He undertook the enormous project of a decorated chapel at the Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, designing the chapel himself and modelling it on Giotto’s Arena Chapel in Padua. This work consisted of sixteen huge paintings depicting everyday scenes of shell-shocked troops in England and Macedonia, but with an emphasis on everyday events rather than the horrors of war. He was commissioned as a war artist during 1939-45 and completed paintings of shipbuilding on the Clyde which are now in national collections. But his main creative impetus was spent, and he died of cancer in 1956, the same year as he received a knighthood.

![]() Stanley Spencer: illustrated biography – Amazon UK

Stanley Spencer: illustrated biography – Amazon UK

![]() Stanley Spencer: illustrated biography – Amazon US

Stanley Spencer: illustrated biography – Amazon US

![]() Stanley Spencer (British Artists series) – Amazon UK

Stanley Spencer (British Artists series) – Amazon UK

![]() Stanley Spencer (British Artists series) – Amazon US

Stanley Spencer (British Artists series) – Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on art

More on media

More on design