tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

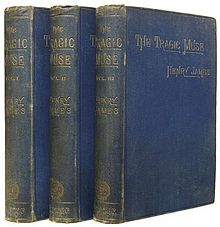

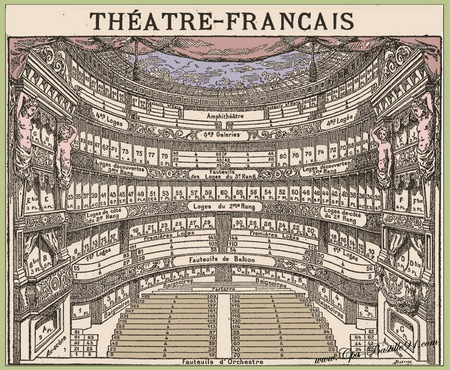

The Outcry (1911) was Henry James’s last novel before he died in 1916. It’s quite unlike most of his major works – light, short, and with even a happy ending. In common with some of his other novels from the ‘late period’ (such as The Other House) it’s based on an idea he had for a stage play. In fact the dialogue had already been written. James merely furnished some connecting passages between the highly stylised conversations.

It deals with a theme which was of contemporary interest – the buying up of European art treasures by rich American art collectors and capitalists – something James had touched on earlier in the figure of Adam Verver in The Golden Bowl. And the novel caught the public’s attention. It sold more copies than his other far more serious later works. It has to be said that the possible reason for this is that the novel is shorter and more easily understandable than the long and intellectually demanding works of his late period.

Henry James – by John Singer Sargeant

The Outcry – critical commentary

This is another of the late novels that James’s originally conceived for the theatre, and following the conventions of dramatic structure and narrative devices that it exists in almost a genre of its own, alongside The Awkward Age and The Other House as a novelised drama – what we would now call ‘the book of the play’.

Although it deals with the well tried Jamesian themes of New World forcefulness and acquisition pitted against Old Europe’s stiff and cautious traditions, the novel ends on what is for James an unusually light and positive note. Two couples, Lord Theign and Lady Sandgate, then his daughter Lady Grace and Hugh Crimble are happily united. There is none of the usual moral ambiguity and negative resolution of James’s other late work. What triumphs is generosity of spirit and a gesture which puts public good before private advantage. No wonder the novel was popular and a best-seller.

It has to be said however that these very elements may have contributed to The Outcry becoming one of James’s least-known and little-read works today. Because despite the fact of its success on first publication, it is now almost universally ignored.

The Outcry – study resources

![]() The Outcry – New York Review Books edition – Amazon UK

The Outcry – New York Review Books edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Outcry – New York Review Books edition – Amazon US

The Outcry – New York Review Books edition – Amazon US

![]() The Outcry – Penguin Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Outcry – Penguin Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Outcry – Penguin Classics edition – Amazon US

The Outcry – Penguin Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() The Works of Henry James – Kindle eBook edition (60 book anthology)

The Works of Henry James – Kindle eBook edition (60 book anthology)

![]() The Complete Plays of Henry James – Oxford: OUP – Amazon UK

The Complete Plays of Henry James – Oxford: OUP – Amazon UK

![]() The Outcry – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

The Outcry – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

The Outcry – plot summary

Book First. The action takes place at Dedborough, the country house of Lord Theign. He is a wealthy aristocrat with two daughters giving him problems. The eldest, Lady Kitty is a widow with substantial gambling debts owed to a duchess. The duchess’s son, Lord John, is paying court to Theign’s younger daughter, Lady Grace, with a proposal that if it is accepted, means that the debts will be written off as part of the marriage settlement.

Meanwhile Beckenridge Bender, a rich American collector arrives at Dedborough at Lord John’s invitation to buy up any rare and expensive art objects. At the same time Grace has invited Hugh Crimble, a young art connoisseur, to look over her father’s collection. He discovers that a lesser painting might in fact be a rare and undiscovered work by an old master, Mantovano.

He also finds that a Rubens in the collection has been falsely attributed, but agrees not to make his findings public so long as they agree not to let prize pieces from the collection to be sold off and taken out of the country. When he tries to pressure Lord Theign to retain the paintings as part of the national heritage, he is dismissed. But Lady Grace takes on his services instead, which displeases her father.

He also finds that a Rubens in the collection has been falsely attributed, but agrees not to make his findings public so long as they agree not to let prize pieces from the collection to be sold off and taken out of the country. When he tries to pressure Lord Theign to retain the paintings as part of the national heritage, he is dismissed. But Lady Grace takes on his services instead, which displeases her father.

Book Second. The action takes place three or four weeks later in the Bruton Street home of Lady Sandgate, an old friend of Lord Theign’s. She receives Crimble, who is waiting for news confirming his attribution of the Mantovano. Crimble and Grace agree to urge Bender to seek maximum publicity for his purchases in order that he should fail – by arousing public animosity.

Crimble receives bad news on his attribution from one expert, but seeks a second opinion elsewhere. Lord Theign argues with Grace on the issue of selling paintings from his collection, and he particularly disapproves of her dealings with Crimble, with whom he forbids her to associate. She disobeys him.

Book Third. Events take place in the same location, a fortnight later. Crimble, whilst waiting for the second opinion on his art-detective work, forms a romantic alliance with Grace. Lord Theign spars with Bender over the price he will charge for his painting, and the deal is further complicated when Lady Sandgate also puts one of her own old masters into the equation.

It is confirmed that the Mantovano is a rare and priceless old master. Crimble is vindicated and his reputation as an expert established. Lord Theign and Lady Sandgate finally agree to thwart Bender by giving their family portraits to the Nation, and the deal is sealed with a romantic coupling.

Principal characters

| Lord Theign | owner of Dedborough Place – a country estate |

| Banks | Lord Theign’s butler |

| Lady Amy Sandgate | an old friend of Lord Theign |

| Lady Kitty Imber | Lord Theign’s widowed elder daughter who has extensive gambling debts |

| Lady Grace | Lord Theign’s younger daughter |

| Lord John | a friend of Lord Theign |

| The Duchess | Lord John’s mother, to whom the gambling debts are owed |

| Beckenridge Bender | a rich American art collector |

| Hugh Crimble | an art conoisseur and scholar |

| Gotch | Lady Sandgate’s butler |

| The Prince | (who never appears) |

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel – the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian father. She has a handsome young suitor – but her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant town house. Who wins out in the end? You will be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, with a sensitive picture of a woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel – the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian father. She has a handsome young suitor – but her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant town house. Who wins out in the end? You will be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, with a sensitive picture of a woman’s life. ![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2011

More on Henry James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

With her large legacy, Isabel travels the Continent and meets an American expatriate, Gilbert Osmond, in Florence. Although Isabel had previously rejected both Warburton and Goodwood, she accepts Osmond’s proposal of marriage. She is unaware that this marriage has been actively promoted by the accomplished but untrustworthy Madame Merle, another American expatriate, whom Isabel had met at the Touchetts’ estate.

With her large legacy, Isabel travels the Continent and meets an American expatriate, Gilbert Osmond, in Florence. Although Isabel had previously rejected both Warburton and Goodwood, she accepts Osmond’s proposal of marriage. She is unaware that this marriage has been actively promoted by the accomplished but untrustworthy Madame Merle, another American expatriate, whom Isabel had met at the Touchetts’ estate. The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

With Kate as a companion, Milly goes to see an eminent physician, Sir Luke Strett, because she’s afraid that she is suffering from an incurable disease. The doctor is noncommittal but Milly fears the worst. Kate suspects that Milly is deathly ill. After the trip to America where he had met Milly, Densher returns to find the heiress in London. Kate wants Densher to pay as much attention as possible to Milly, though at first he doesn’t quite know why. Kate has been careful to conceal from Milly (and everybody else) that she and Densher are engaged.

With Kate as a companion, Milly goes to see an eminent physician, Sir Luke Strett, because she’s afraid that she is suffering from an incurable disease. The doctor is noncommittal but Milly fears the worst. Kate suspects that Milly is deathly ill. After the trip to America where he had met Milly, Densher returns to find the heiress in London. Kate wants Densher to pay as much attention as possible to Milly, though at first he doesn’t quite know why. Kate has been careful to conceal from Milly (and everybody else) that she and Densher are engaged.