estate, castle, house, gardens, and their history

Sissinghurst is the country estate with castle in Kent that was restored and developed by Vita Sackville West as a compensation for the disappointment at not inheriting her 365 room ancestral home at Knole. Together with her husband Harold Nicolson she created a particularly fine set of gardens which have become famous with horticulturalists throughout the world. On the death of their son Nigel Nicolson in 1967, ownership of the house and its grounds passed to the National Trust in lieu of inheritance taxes, and its current tenants are the grandson Adam Nicolson and his family. This is a beautifully written account of his attempts to restore traditional Kentish farming methods to make the estate ecologically sound and self-sustaining.

But more than that it is his celebration of the countryside, its vegetation, cultivation, rural industries, and its history. The story begins with his boyhood discovery of rural life, very lyrically evoked in a manner that echoes Georgian nostalgia, even though he is dealing with a period as recent as the 1960s. He was fascinated by woodcutters, hop-stringing, sheep dipping, and all the apparatus of farming methods, his account of which read like passages from a novel by Thomas Hardy.

Sissinghurst gardens have been open to the public since the late 1930s, but he describes the conversion of the estate from working farm to a National Trust ‘visitor attraction’ with great sadness. When the residency passed into his own hands he researched its history and discovered that it had always been a fertile, productive, and profitable farming enterprise, and felt an urge to restore its traditional character.

He moved in with his family and was immediately served with an imperious and autocratic ‘Occupancy Agreement’ by the National Trust. They specified which rooms he could occupy, which buildings he could enter, and which way round to park his Land Rover. They also ruled that he must ask permission to have visitors and any photographs he took were copyright to the Trust.

He goes into the paleontological roots of the area and its essential foundations in Kentish Weald clay. This is followed by its meteorological history and the development of its plant and animal life, up to the formation of its first roads. His plan was to introduce what is now called mixed farming. There was considerable resistance to the idea – some of it coming from the people at Sissinghurst itself. They thought the reintroduction of chickens and pigs might produce an unpleasant smell for visitors.

The National Trust emerges from all this as an organisation as hidebound, snobbish, and bureaucratic as the stratum of society that it is trying its best to preserve. This is the landed gentry, and the fallen aristocracy who can no longer afford to maintain their own homes.

Nicolson traces the political and economic history of the area, back to the early sixteenth century and the origins of the current estate, its castle, house, and gardens. The degree of detail is quite astonishing. There is even an account of individual trees which have survived for four hundred years. However, after its heyday in the Elizabethan period the house and estate went into decline. Nevertheless, from a study of their history Nicolson draws the lesson that the estate could survive if it were treated as an organic whole.

Woven into this account are passages concerning his family history and the history of Kent. He paints a very sad picture of his grandfather Harold Nicolson in his eighties, reduced by a series of strokes to a state of humiliated debility that left him wishing for death. His own father comes across as remote, cold, and unloving. And yet the house was stuffed with thousands of letters written by his grandparents, parents, and their lovers and friends from the Bloomsbury Group, professing their love for each other. On this topic he astutely observes:

How much of it was real? Was this world of written intimacy and posted emotion, of long distance paternal and filial love, in fact a simulacrum of the real thing? A substitute for it? Nicolson closeness has been a written performance for a hundred years. And that unbroken fluency in the written word made me think that it concealed some lack. If closeness were the reality, would it need to be so often declared?

He ends with a retelling of his grandparents’ famously bizarre marriage and Vita Sackville West’s scandalous elopement with Violet Trefusis which Nicolson’s own father revealed in Portrait of a Marriage. It was Vita’s money that bought Sissinghurst, and he makes a good case for her putting her own stamp on the restoration of its fortunes – though the famous gardens were also part-designed by her husband.

It was Vita who went on to write a long series of articles about gardens for the Observer between 1947 and 1961. These gave her an opportunity to write about Sissinghurst in a way that brought it to the attention of the world – even though she never named it in the articles. The income from this writing was invested straight back in the development of the estate.

The National Trust eventually ceased its hostilities towards Adam Nicolson’s plans, and he was given the financial support and the time to prove that they could work. So the story has a happy ending, but as he points out in his sub-title, the process of organic farming and estate management is one that does not have any neat closure. He sees it as part of the history of a place.

© Roy Johnson 2015

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Adam Nicolson, Sissinghurst: An Unfinished History, London: HarperCollins, 2008, pp.342, ISBN: 0007240554

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

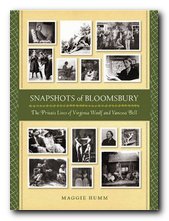

From 1890 onwards the Kodak portable camera was both heavily promoted and enthusiastically taken up by female amateurs. Virginia and Vanessa took the photographs, developed them, printed them, and mounted them in albumns. And the Stephen sisters were not alone in their activity. Many of the other

From 1890 onwards the Kodak portable camera was both heavily promoted and enthusiastically taken up by female amateurs. Virginia and Vanessa took the photographs, developed them, printed them, and mounted them in albumns. And the Stephen sisters were not alone in their activity. Many of the other

Between the Acts

Between the Acts The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth