classical music in the twentieth century

Alex Ross is the music critic for the New Yorker magazine who blogs prolifically at The Rest is Noise. And even though he doesn’t have comments switched on at his site, his postings are required reading for anyone who wants to keep abreast of classical music – especially as seen from New York city. His tastes and references are amazingly eclectic and unstuffy. One minute he’s analysing the latest staging of the Ring Cycle and next he’s reporting on developments in contemporary rock music or a recently discovered private recording of a John Coltrane radio broadcast.

This is his long-awaited first book and major oeuvre as a critic, tracing the development of twentieth century classical music from the first night of Strauss’s Salome (no accent) in 1905 to John Adams‘s Nixon in China in 1987. He has an amazingly developed sense of cultural history- reminding us whilst discussing the development of Thomas Mann‘s traditional musical ideas in relation to Schoneberg that Leon Trotsky spent the years 1907 to 1914 in exile in Vienna where these modernist moves were being played out, alongside the work of Karl Kraus, Oskar Kokoshka, and Egon Schiele. He darts back and forth in time in a way which is at first bewildering, but there’s a good reason for doing so – usually to show how far back cultural convergences began.

This is his long-awaited first book and major oeuvre as a critic, tracing the development of twentieth century classical music from the first night of Strauss’s Salome (no accent) in 1905 to John Adams‘s Nixon in China in 1987. He has an amazingly developed sense of cultural history- reminding us whilst discussing the development of Thomas Mann‘s traditional musical ideas in relation to Schoneberg that Leon Trotsky spent the years 1907 to 1914 in exile in Vienna where these modernist moves were being played out, alongside the work of Karl Kraus, Oskar Kokoshka, and Egon Schiele. He darts back and forth in time in a way which is at first bewildering, but there’s a good reason for doing so – usually to show how far back cultural convergences began.

His narrative is spiced by what might be called the higher musical gossip. He slips in references and anecdotes which sparkle like gems on the page. Schoneberg’s bon mot on his exile in California: ‘I was driven into Paradise’, and Charlie Parker spontaneously quoting from The Firebird when he spotted Igor Stravinsky was in the audience at Birdland one night.

It’s an approach which relies heavily on anecdote and cultural montage – but his juxtapositions are all backed up by scholarly references which are kept wisely at the back of the book, They don’t encumber the narrative.

His descriptions of symphonies and major orchestral works are a mixture of technical analysis and an impressionistic account of what is going on:

In the last bars, the note B aches for six slow beats against the final C-major chord, like a hand outstretched from a figure disappearing into light.

Maybe the mixture is just about right. After all, it’s difficult to write about music, which is essentially abstract. When you think about it, music doesn’t mean anything, even though it can be incredibly moving and beautiful. Though that, of course, is meaning of a kind.

The Spirit of Schoenberg presides over the first part of the book: all other music seems to be measured against his purist ethos and practice. This phase ends with the premiere of Berg’s Lulu in 1937. My only disappointment in this section was his account of Duke Ellington, which concentrated on his not-to-be-performed opera Boola and failed to bring out the element of small-scale symphonies or concertos which characterised much of his sub three-minute compositions for 78 rpm recordings.

In the second part, Shostakovich is let off the hook somewhat. As a way of explaining his capitulation to Stalinism, Ross describes him as having ‘divided selves’ – though to do him credit, Ross doesn’t try to conceal the privileges he enjoyed (spacious Moscow flat with three pianos, for which he thanked Stalin personally) whilst his contemporaries were being led of to the Gulag or despatched with a bullet in the back of the head.

It’s interesting to read of the style wars of the 1940s and 1950s with the benefit of half a century’s hindsight. Major composers such as Stravinsky were being written off by people who are now forgotten – and it’s even more amazing to read that the champions of atonal music and the concerts arranged to promote them were funded by the CIA.

Ross clearly has his heroes – Strauss (despite his Nazi associations) Schoenberg, and Stravinsky. And even though he may not have intended it, Pierre Boulez emerges from the narrative as a distinctly pushy, unpleasant piece of self-aggrandisement.

I was surprised that he took John Cage so seriously – somebody who has always struck me as completely bogus – but he gives a touching account of Aaron Copland, who suffered harassment and criticism in his own country during the McCarthy trials for his leftish sympathies, despite his having written such iconic evocations of America as Appalachian Spring and Fanfare for the Common Man

There’s a whole chapter on Benjamin Britten, where I was glad to see that Ross doesn’t shy away from the much-ignored fact that much of Britten’s work deals with the sexual and emotional violation of young boys. He even reveals that Britten (in a Michael Jackson moment) took the juvenile star of his 1954 The Turn of the Screw (David Hemmings) into his own bed. But Ross’s account of Britten is far from smutty. There’s a several page long account of Peter Grimes which is the most extended musical analysis in the whole book.

He ends his narrative with an account of the American minimalists – the music still apparently split into two camps, but this time ‘uptown’ and ‘downtown’ – and he has a roundup of developments in Europe following the collapse of communism and the Berlin Wall. His story concludes with a part-wish, half-expectation that classical and popular music will somehow embrace each other in a way which will create new forms in the twenty-first century.

This is a very readable, indeed a compelling work which combines love of the subject with a detailed knowledge of its history and cultural context. It’s the sort of book that makes you feel like reading with a piano keyboard to hand in order to follow the formal sequences and chord progressions he describes. Unmissable for anyone interested in twentieth century music.

© Roy Johnson 2007

Alex Ross, The Rest is Noise: listening to the twentieth century, New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2007, pp.624, ISBN: 0374249393

More on music

More on media

More on lifestyle

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice.

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice. Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.

Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.

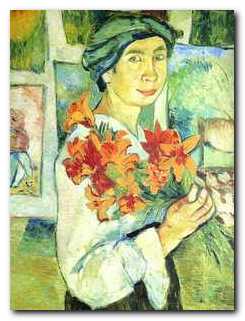

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.