a chronicle of events, literatures, politics, and the arts

1895. X-rays discovered; invention of the cinematograph; trial and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde; Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband; H.G. Wells, The Time Machine.

1896. Wireless telegraphy invented; Abyssinians defeat occupying Italian forces – first defeat of colonising power by natives; Thomas Hardy, Jude the Obscure; Anton Chekhov, The Seagull; Daily Mail first published.

1897. Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee; Henry James, The Spoils of Poynton , What Masie Knew; Bram Stoker, Dracula.

1898. Second Anglo-Boer War begins. Henry James, The Turn of the Screw ; Thomas Hardy, Wessex Poems; George Bernard Shaw, Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant; H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds.

1899. British disasters in South Africa. Schoenberg Verklarte Nacht; Henry James, The Awkward Age; Kate Chopin, The Awakening; Anton Chekhov, Uncle Vanya.

1900. Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim; Deaths of Nietzsche, Wilde, and Ruskin; Max Planck announces quantum theory. Daily Express started.

1901. Queen Victoria dies – Edwardian period begins; First wireless communication between UK and USA; H.G.Welles, The First Men in the Moon; Rudyard Kipling, Kim; First Nobel prize for literature – R.P.A.Sully Prudhomme (F).

1902. End of Boer War; Henry James, The Wings of the Dove;

Arnold Bennett Anna of the Five Towns; Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness; Nobel prize – T. Mommsen (G).

Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Literature in English is a new reference guide to English-language writers and writing throughout the present century, in all major genres and from all around the world – from Joseph Conrad to Will Self, Virginia Woolf to David Mamet, Ezra Pound to Peter Carey, James Joyce to Amy Tan. Includes entries on literary movements, periodicals, and over 400 individual works, as well as articles on some 2,400 authors, plus a good introduction by John Sutherland.

Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Literature in English is a new reference guide to English-language writers and writing throughout the present century, in all major genres and from all around the world – from Joseph Conrad to Will Self, Virginia Woolf to David Mamet, Ezra Pound to Peter Carey, James Joyce to Amy Tan. Includes entries on literary movements, periodicals, and over 400 individual works, as well as articles on some 2,400 authors, plus a good introduction by John Sutherland.

1903. First flight in heavier-than-air machine by Wright brothers in USA; first silent movie, The Great Train Robbery; Henry James, The Ambassadors; Daily Mirror started; Nobel prize – B. Bjornson (N).

1904. New York subway opens; Russo-Japanese war begins; Henry James, The Golden Bowl; Joseph Conrad, Nostromo; Anton Chekhov, The Cherry Orchard; Death of Chekhov; Nobel prize – F. Mistral (F) and J. Echegary (Sp).

1905. ‘Bloody Sunday’ massacre of protesters in St Petersburg; Einstein, Special Theory of Relativity; Freud, Theory of Sexuality; E.M. Forster, Where Angels Fear to Tread; Nobel prize – H. Sienkiewicz (P).

1906. First Liberal government in UK; death of Ibsen; General strike in Russia – followed by first (limited) democratic parliament; Women’s Suffrage movement active; San Francisco destroyed by earthquake and fire; Labour Party formed. Nobel prize – G. Carducci (I)

1907. Belgium seizes Congo; Austria seizes Bosnia and Herzegovina; Picasso introduces cubism; first electric washing machine; Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent; E.M.Forster, The Longest Journey; Nobel prize – Rudyard Kipling (UK)

1908. Ford introduces Model-T; Elgar’s First Symphony; E.M.Forster, A Room with a View; first Old Age Pensions; Nobel prize – R. Eucken (G)

1909. Ford produces first cheap cars – Model T; Death of George Meredith; Bleriot flies across English Channel; Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto; Vaughn Williams Fantasy on a Theme of Thomas Tallis; Nobel – S. Lagerlöf (S)

Twentieth-century Britain is an account of political, industrial, commercial, and cultural development in England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. It’s particularly strong on the changing face of government, and it also relates issues of the day to the great writers and artists of the period. This ‘very short introduction’ series offers a potted account of the subject in handy pocket-book format, with plenty of suggestions for further reading.

Twentieth-century Britain is an account of political, industrial, commercial, and cultural development in England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. It’s particularly strong on the changing face of government, and it also relates issues of the day to the great writers and artists of the period. This ‘very short introduction’ series offers a potted account of the subject in handy pocket-book format, with plenty of suggestions for further reading.

1910. Death of Tolstoy, Edward VII, and Florence Nightingale; E.M.Forster, Howards End; Arnold Bennett, Clayhanger; H.G.Wells, The History of Mr Polly; Nobel prize – P. Heyse (G).

1911. Rutherford discovers structure of atom in Manchester; Chinese revolution; Joseph Conrad, Under Western Eyes; D.H. Lawrence, The White Peacock; Nobel prize – M. Maeterlink (Be).

1912. China becomes a republic following revolution; Sinking of the Titanic; railway, mining, and coal strikes in UK. Daily Herald started; Schoenberg Pierrot Lunaire; Nobel prize – G. Hauptmann (G)

1913. New Statesman started; first crossword puzzle; Thomas Mann, Death in Venice; D.H. Lawrence, Sons and Lovers; Stravinsky The Rite of Spring; Nobel prize – R. Tagore (In)

1914. Outbreak of first world war; first traffic lights; Panama Canal opened; James Joyce, Dubliners; Marcel Proust begins to publish A la recherche du temps perdu (Remembrance of Things Past); Nobel prize – not awarded.

1915. First air attacks on London; Germans use poison gas in war; Franz Kafka, Metamorphosis; Einstein, General Theory of Relativity; D.H. Lawrence, The Rainbow; Ford Maddox Ford, The Good Soldier; D.W.Griffith, The Birth of a Nation; Nobel prize – R. Roland (F).

1916. First Battle of the Somme; Battle of Verdun; Australians slaughtered in Gallipoli campaign; Easter Rising in Dublin; James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; Prokofiev Classical Symphony; Nobel prize – V. von Heidenstam (S).

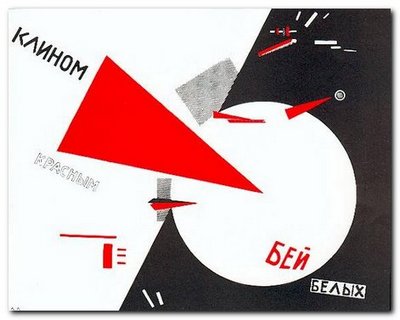

1917. USA enters the war; October Revolution in Russia; battle of Passchendaele; T.S. Eliot Prufrock and Other Observations; Nobel prize – K. Gjellerup (D) and H. Pontoppidan (Da).

1918. Second Battle of the Somme; German offensive collapses; end of war [Nov 11]; Votes for women over 30; influenza pandemic kills millions; Lytton Strachey, Eminent Victorians; Nobel prize – not awarded.

1919. Peace Treaty ratified at Versailles; Einstein’s Relativity Theory confirmed during solar eclipse; Breakup of former Habsburg Empire; Alcock and Brown make first flight across Atlantic; prohibition in US; Ronald Firbank, Valmouth; Franz Kafka, In the Penal Colony; Nobel prize – K. Spitteler (Sw).

© Roy Johnson 2005

Twentieth century literature

More on language

More on literary studies

More on grammar

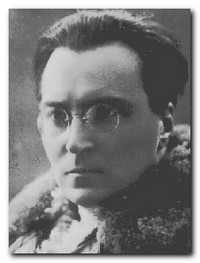

Serge was arrested in 1933, held in solitary confinement, and interrogated endlessly, accused of ‘crimes’ based on the confessions of others which the GPU had actually written. Refusing to co-operate with his captors, he was exiled to Orenberg on the borders of Kazakhstan. He lived there with his son Vlady for the next three years, cold, hungry, and under constant surveillance – but at least free to write. He produced Les Hommes perdus a novel about pre-war French anarchists, and La Tourmente, a sequel to Conquered City. He despatched several copies to Romain Rolland for publication in Paris, but they were ‘lost’ in the post. Ironically, the Post Office was obliged to compensate him for each loss, and he earned ‘as much as a well-paid technician’. He shared the money he earned and the support he received from western Europe with his fellow exiles – on one occasion dividing a single olive with his fellow inmates, who had never tasted one before.

Serge was arrested in 1933, held in solitary confinement, and interrogated endlessly, accused of ‘crimes’ based on the confessions of others which the GPU had actually written. Refusing to co-operate with his captors, he was exiled to Orenberg on the borders of Kazakhstan. He lived there with his son Vlady for the next three years, cold, hungry, and under constant surveillance – but at least free to write. He produced Les Hommes perdus a novel about pre-war French anarchists, and La Tourmente, a sequel to Conquered City. He despatched several copies to Romain Rolland for publication in Paris, but they were ‘lost’ in the post. Ironically, the Post Office was obliged to compensate him for each loss, and he earned ‘as much as a well-paid technician’. He shared the money he earned and the support he received from western Europe with his fellow exiles – on one occasion dividing a single olive with his fellow inmates, who had never tasted one before.