tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

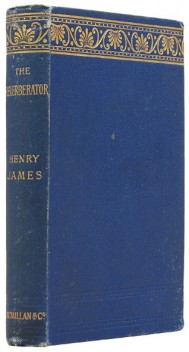

The Reverberator is a short novel (especially short by Henry James’s standards) which was first serialised in Macmillan’s Magazine between February and July in 1888. Later the same year it was published as a two volume then a one volume novel. It deals with issues which are amazingly contemporary – the power of the press, the individual’s right to privacy, and the journalism of celebrity gossip.

first edition 1888

The Reverberator – critical commentary

Most of Henry James’s earlier works first appeared serialized in newspapers and magazines. He was well acquainted with the practicalities and the economics of publishing, but more importantly he was aware of the essential nature of journalism, which in the nineteenth century as now in the twenty-first was a force for potential mischief as well as for spreading enlightened intelligence.

The novel deals with three elements which still affect the public’s ambivalent relationship with the popular press: the promotion of celebrity gossip for commercial gain; the public’s ‘right to know’ (about the behaviour of the upper classes); and an individual’s right to privacy.

George Flack is an early example of a type we have seen over and again at the recent (UK) Leveson Inquiry into the behaviour of the press – the muck-raking journalist who is quite frank about his unscrupulous methods of obtaining information, and whose defense rests on the argument that he is merely supplying a public demand.

Flack tells Francie what information he wants from her, and reveals what use he will make of it. On his part, there is no concealment or pretence. The Probert family wish to preserve their right to privacy, including details such as adultery and petty theft by members of the family. There is even an argument made (without any supporting evidence) that the members of the family secretly enjoy the notoriety that Flack’s article affords them. All of these issues have emerged at the Leveson Enquiry: Henry James was writing about them 124 years earlier.

As a further illustration of fundamental journalistic practices, it is worth noting that Flack has a general brief to gather information and fashionable subjects, but the smaller details of his creations are supplied by what we would now call local ‘runners’. It is Miss Topping who digs out the embarrassing facts of the Probert family behaviour and passes them to Flack as the scandalous meat of his article..

James was to explain these issues again in his 1903 story The Papers which deals with the deliberate creation of celebrity culture via publicity fuelled corrupt journalism. James was personally very sensitive to the question of privacy, and protected his own by eventually burning a lot of his private papers

It is worth noting that whilst the Probert family wishes to protect its privacy and takes pride in social connections that go back ‘a thousand years’, Gaston pére and his children are in fact Americans who have married into French society. They are emigrants from Carolina.

The Reverberator – study resources

![]() The Reverberator – Melville House paperback – Amazon UK

The Reverberator – Melville House paperback – Amazon UK

![]() The Reverberator – Melville House paperback – Amazon US

The Reverberator – Melville House paperback – Amazon US

![]() The Reverberator – Kindle edition [FREE]

The Reverberator – Kindle edition [FREE]

![]() The Reverberator – Digireads paperback – Amazon UK

The Reverberator – Digireads paperback – Amazon UK

![]() The Reverberator – Digireads paperback – Amazon US

The Reverberator – Digireads paperback – Amazon US

![]() The Reverberator – Library of America – Amazon UK

The Reverberator – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() The Reverberator – Library of America – Amazon US

The Reverberator – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Reverberator – eBook versions at Gutenberg

The Reverberator – eBook versions at Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

The Reverberator – plot summary

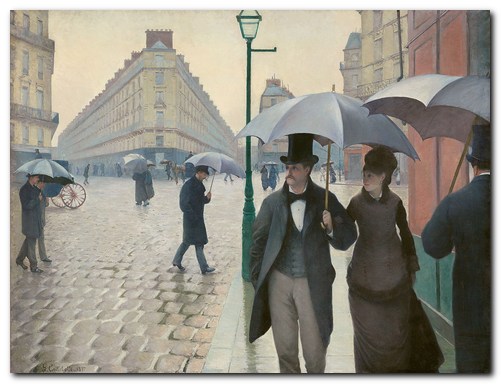

Newspaper society journalist George Flack visits Fidelia and Francina Dosson at their Paris hotel, having met them the previous year on a transatlantic crossing. He introduces them to Parisian life and persuades Francie to have her portrait painted by a ‘rising Impressionist’, George Waterlowe, through whom they meet his friend Gaston Probert, an American who was born in Paris.

Delia has ambitions for her younger sister – an engagement, but not yet marriage. Gaston is taken by Francie and he wants to know what it would be like to be a ‘real’ American. George Flack and Gaston are rivals for Francie.

Falk has ambitions for his newspaper the Reverberator, and he proposes marriage to Francie, who turns him down. Some months later, whilst Falk has returned to the USA, Gaston is torn between his love for Francie and a social reserve on behalf of his sisters, who have married into rather snobbish upper-class French society. He arranges for his sister Suzanne to meet Francie, but she refuses to endorse his plan to marry her. Gaston ask Mr Dosson’s permission to marry his daughter, and gets his approval.

Members of Gaston’s family eventually consent to meet the Dossons in order to approve them socially, and all appears to be going well. But Mr Probert pére still has reservations based on grounds of class distinctions and family traditions. American-based business connections require Mr Dosson to leave, but since this would leave his two unmarried daughters unchaperoned, Gaston is asked to go in his place.

Flack returns from America and asks Francie to take him to see the portrait, because he wants to write about it for the Reverberator. On visiting, he is snubbed by Gaston’s sister Mme de Cliché, but Francie talks to him freely about the family into which she is about to be married.

When Flack writes a gossip article about the portrait and the family in the Reverberator, they are all incandescent with rage and summon Francie to a family summit meeting, which is inconclusive. Mr Dosson takes a nonchalant attitude to the affair and wonders why anyone should get upset about an article in a newspaper. When Gaston returns from the USA, Francie admits that she has supplied Flack with the information for his article.

Mr Dosson writes to Flack in Nice, who then visits Francie, justifies his article, castigates the Proberts, and declares his love for her. She rejects him, but says that she will not marry Gaston.

Gaston visits the Dossons and vainly tries to make them compromise for the sake of the Proberts’ family pride. Francine and her father refuse. Gaston seeks advice from Waterlowe, who says he must reject his family in order to create a sense of freedom and independence for himself. Even though his father cuts him off with no money, that’s what Gaston does, and Francie accepts him.

Principal characters

| George Flack | the European correspondent for the American newspaper, The Reverberator |

| Whitney Desson | a rich American financier |

| Miss Fidelia Desson | his plain but sensible elder daughter |

| Miss Francina Desson | his pretty but naive younger daughter |

| Charles Waterlowe | an American ‘rising Impressionist’ painter in Paris |

| Gaston Probert | an American who was born in Paris and has never been to America |

| Countess Suzanne de Brécourt | Gaston’s sister |

| Mme Marguerite de Cliché | Gaston’s sister |

| Mme Jeanne de Douves | Gaston’s sister |

| Mr Probert | Gaston’s distinguished father (originally from Carolina) |

| Miss Topping | Flack’s assistant journalist in Paris (who never appears) |

Setting

The setting throughout the novel is Paris, but it is worth noting that all the characters in the story are American – either visiting on a long term basis (the Dossons) resident (Flack) or born there (Probert). Two characters (Flack and Probert) visit America during the course of events, but this is merely a plot device to get them temporarily off stage.

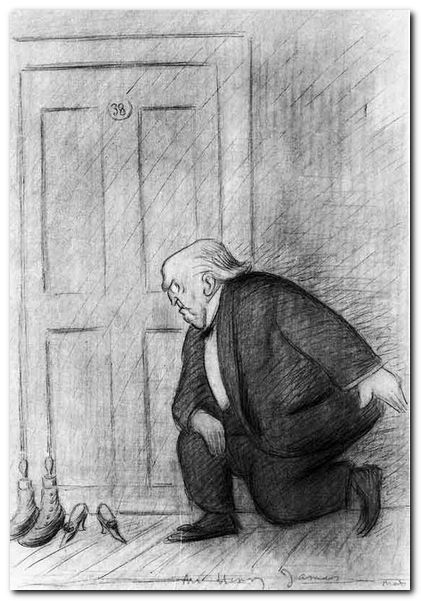

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2012

More on Henry James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended. Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness Nostromo

Nostromo

The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

K is visited by his uncle, who is a friend of a lawyer. The uncle seems distressed by K’s predicament. At first sympathetic, he becomes concerned K is underestimating the seriousness of the case. The uncle introduces K to an advocate, who is attended by Leni, a nurse, who K’s uncle suspects is the advocate’s mistress. K. has a sexual encounter with Leni, whilst his uncle is talking with the Advocate and the Chief Clerk of the Court, much to his uncle’s anger, and to the detriment of his case.

K is visited by his uncle, who is a friend of a lawyer. The uncle seems distressed by K’s predicament. At first sympathetic, he becomes concerned K is underestimating the seriousness of the case. The uncle introduces K to an advocate, who is attended by Leni, a nurse, who K’s uncle suspects is the advocate’s mistress. K. has a sexual encounter with Leni, whilst his uncle is talking with the Advocate and the Chief Clerk of the Court, much to his uncle’s anger, and to the detriment of his case.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis Amerika

Amerika

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf