Modernism 1915—1925

Dada is one of those movements in modern art which had an amazingly short life but a lasting influence. It flourished for not much more than the decade between 1915 and 1925, yet some of its legacy is still with us. It’s amazing to think that this influential movement sprang up in the middle of the first world war – though there were pre-echoes of it in the work of abstract expressionism and Russian futurism which just preceded it.

Tristan Tzara might have thought up the name Dada, but I doubt that anyone reads a word of what he wrote these days. However, the work of visual artists such as Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber still speaks as something of lasting value, almost 100 years later. Dadaism was certainly what we would now call a multimedia phenomenon. It involved painting and sculpture, poetry, typography, theatre, and performance art. At one point it even included a boxing match between Jack Johnson – first black world champion – and Arthur Cravan, a poet-boxer Dadist who was the nephew of Oscar Wilde.

Tristan Tzara might have thought up the name Dada, but I doubt that anyone reads a word of what he wrote these days. However, the work of visual artists such as Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber still speaks as something of lasting value, almost 100 years later. Dadaism was certainly what we would now call a multimedia phenomenon. It involved painting and sculpture, poetry, typography, theatre, and performance art. At one point it even included a boxing match between Jack Johnson – first black world champion – and Arthur Cravan, a poet-boxer Dadist who was the nephew of Oscar Wilde.

What came out of it that will be of enduring value? Well, certainly the use of montage in graphic design is still with us, as is production in what we now call ‘mixed media’. The work of Raoul Hausmann, Georg Groz, John Heartfield, and Kurt Schwitters still seems fresh today – though Schwitters was actually refused membership of the ‘official’ Dada group, to which he responded by setting up his own one-man movement, called Merz.

As a ‘movement’ (though it was never coherent) it spread quickly from its birthplace in Zurich to Berlin, Paris, and even New York. But its principal adherents were forever disagreeing with each other or even repudiating their own former beliefs. By the early 1920s Dada was ready to be swept up by the much stronger forces of surrealism.

This monograph is beautifully illustrated and it ends with a collection of the key declarations and manifestos of the period for those who want a taste of what was thought to be radical protest in art at the time. There’s also a very good bibliography. Pocket size in format and price, it’s an excellent introduction to the subject.

© Roy Johnson 2007

Marc Dachy, Dada: The Revolt of Art, London: Thames and Hudson, 2006, pp.127, ISBN 0500301190

More on art

More on media

More on design

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was an artist and bohemian who loved and was loved by both men and women. She was born Dora de Houghton Carrington in Hereford, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. As a somewhat wilful youngster, she found her family background quite stifling, adoring her father and loathing her mother. She attended Bedford High School, which emphasized sports, music, and drawing. The teachers encouraged her drawing and her parents paid for her to attend extra art classes in the afternoons. In 1910 she won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and studied there with Henry Tonks.

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was an artist and bohemian who loved and was loved by both men and women. She was born Dora de Houghton Carrington in Hereford, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. As a somewhat wilful youngster, she found her family background quite stifling, adoring her father and loathing her mother. She attended Bedford High School, which emphasized sports, music, and drawing. The teachers encouraged her drawing and her parents paid for her to attend extra art classes in the afternoons. In 1910 she won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and studied there with Henry Tonks.

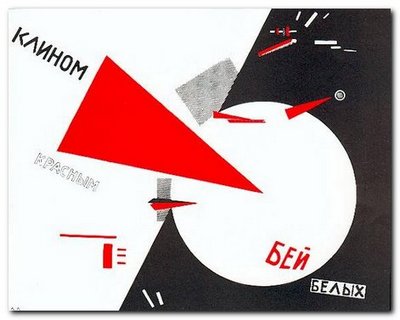

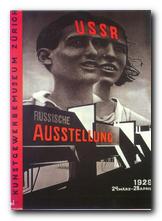

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.