essays in literary, media, and cultural studies

As editor Maggie Humm points out in her introduction to this huge collection of scholarly studies on Virginia Woolf and the Arts, Woolf spent her entire life surrounded by creative people of all kinds. Her father was an internationally renowned writer (on belle lettres and moutaineering), her sister was a painter, and her friend Roger Fry both a critic and an artist. Virginia Woolf visited contemporary exhibitions, travelled to museums abroad, and participated in aesthetic debates via her prolific output of essays and journalism.

The essays are grouped under headings of Aesthetic Theory, Painting, Domestic Arts, Publishing, Broadcasting and Technology, Visual Media, and Performance Arts. At their best they illuminate the fact that Virginia Woolf had original opinions and novel forms of expressing them on a variety of subjects, ranging from human behaviour to painting, urban and domestic life, social history, and the relationship between memory, consciousness, and time.

The essays are grouped under headings of Aesthetic Theory, Painting, Domestic Arts, Publishing, Broadcasting and Technology, Visual Media, and Performance Arts. At their best they illuminate the fact that Virginia Woolf had original opinions and novel forms of expressing them on a variety of subjects, ranging from human behaviour to painting, urban and domestic life, social history, and the relationship between memory, consciousness, and time.

They cover topics such as Woolf’s depiction of aesthetic creation via painting (To the Lighthouse), Woolf and race [without touching on her anti-Semitism], Woolf and the metropolitan city, and Woolf and realism. Each essay is self-contained, with its own set of endnotes and bibliography of further reading.

At their worst (particularly those dealing with aesthetics and literary theory) they are little more than overblown meditations, dragging apparent meanings out of words (more/Moor/moor) where quite clearly none were intended – like schoolboy puns. They also indulge in settling of scores with other ‘critics’, rather than focusing on authentic literary criticism.

Fortunately, the collection improves as it progresses. The most interesting and effective essays are the least pretentious and the least to do with modern literary criticism in all its silliness. For instance Diane Gillespie on ‘Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, and Painting’ and Benjamin Harvey on Woolf’s visits to art galleries and museums.

Though even amongst the sensible essays there are disappointments. A chapter on ‘Bohemian Lifestyles’ is not much more than a description of Woolf’s relationships with her sister Vanessa, Vita Sackville-West, and Katherine Mansfield. It doesn’t explore any truly radical behaviour – such as Vanessa’s ability to live comfortably alongside her ex-husband and his lover, her own ex-lover and his current (gay) lover, and to conceal from her own daughter the true identity of her father for almost twenty years.

But there are plenty of good chapters – one on ‘Virginia Woolf and Entertaining’, another on Woolf’s sesitivity to gardens, and an especially interesting study of ‘Virginia Woolf as Publisher and Editor’ which spills over quite creatively into the Hogarth Press promotion of Russian Literature.

This leads logically enough into a chapter on ‘Virginia Woolf and Book Design’ which is like a shortened version of John Willis’s full length study Leonard and Viginia Woolf as Publishers: The Hogarth Press 1917-1941. Patrick Collier has a good chapter on Woolf and journalism, which I wish had included consideration of her early reviews for the Manchester Guardian and The Times Literary Supplement in the period 1904-1915.

Pamela Caughie also has an interesting chapter on Virginia Woolf and radio broadcasting that cleverly points out the contradictions in Woolf’s attitude to the BBC – keen to embrace the new technology it offered in the 1920s, but perceptive enough to realise that its early Reithean paternalism was hopelessly middlebrow – a view she shared with her husband Leonard, who put his finger on an attitude which is still prevelent today:

That the BBC should be so reactionary and politically and intellectually dishonest is what one would expect … knowing the kind of people who always get in control of those kind of machines, but what makes them so contemptible is that, even according to their own servants’ hall standards, they habitually choose the tenth rate in everything, from their music hall programmes and social lickspittlers and royal bumsuckers right down their scale to the singers of Schubert songs, the conductors of their classical concerts and the writers of their reviews.

The essays at the latter end of the collection remind us just how au courant Virginia Woolf was with contemporary technology. She took photographs, broadcasted on the radio, and wrote about London’s underground, the telephone, the cinema, and even flying (without having done so). The irony here is that the critics explaining her avant-garde behaviour and interests are themselves locked into a mode that is terminally old-fashioned (the academic essay) almost to the point of being moribund.

This is a huge and very impressive production, but one thing struck me about it – apart from its equally huge cost. Many of the essays take a long time to make a simple point. They circle around the object of enquiry with endless qualifications and even self-refutations, all made in the spirit of ‘interrogating’ their subject. It’s as if we are being offered ‘thinking aloud’ instead of considered arguments and conclusions. Having said that, the audience at which this Woolf-fest is aimed (lecturers and post-graduates) will not want to miss out on a collection that does include studies that link Woolf to many other forms of culture beyond literature alone.

© Roy Johnson 2010

Maggie Humm (ed), The Edinburgh Companion to Virginia Woolf and the Arts, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010, pp.512, ISBN: 0748635521

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group

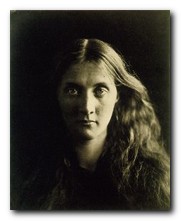

1882. Virginia Woolf born (25 Jan) Adeline Virginia Stephen, third child of Leslie Stephen (Victorian man of letters – first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography) – and Julia Duckworth (of the Duckworth publishing family). Comfortable upper middle class family background. Her father had previously been married to the daughter of the novelist William Makepeace Thackery. Brothers Thoby and Adrian went to Cambridge, and her sister Vanessa became a painter. Virginia was educated by private tutors and by extensive reading of literary classics in her father’s library.

1882. Virginia Woolf born (25 Jan) Adeline Virginia Stephen, third child of Leslie Stephen (Victorian man of letters – first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography) – and Julia Duckworth (of the Duckworth publishing family). Comfortable upper middle class family background. Her father had previously been married to the daughter of the novelist William Makepeace Thackery. Brothers Thoby and Adrian went to Cambridge, and her sister Vanessa became a painter. Virginia was educated by private tutors and by extensive reading of literary classics in her father’s library. Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. An attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject.

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. An attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject. The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf

Vita (Victoria Mary) Sackville-West (1892-1962) was a prolific poet and novelist – though she is probably best known for her writing on gardens and her affair with

Vita (Victoria Mary) Sackville-West (1892-1962) was a prolific poet and novelist – though she is probably best known for her writing on gardens and her affair with

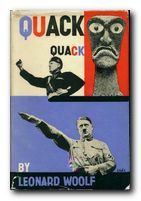

The other Press publications upon which the collection focuses are those by Virginia Woolf herself – all illustrated by her sister Vanessa Bell. There are also examples of the polemical essays published in the 1930s, which included arguments against Imperialism and in favour of feminism (of which Leonard was a champion). A short series of public letters even included ‘A Letter to Adolf Hitler’ by Louis Golding.

The other Press publications upon which the collection focuses are those by Virginia Woolf herself – all illustrated by her sister Vanessa Bell. There are also examples of the polemical essays published in the 1930s, which included arguments against Imperialism and in favour of feminism (of which Leonard was a champion). A short series of public letters even included ‘A Letter to Adolf Hitler’ by Louis Golding.