lifeline, literature, publishing, politics

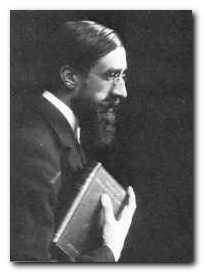

Leonard Sidney Woolf was born in London in 1880, the third of ten children of Solomon Rees Sydney and Marie (de Jongh) Woolf. When his father died in 1892, Woolf was sent to board at the Arlington House School, a preparatory school near Brighton. From 1894 to 1899 he studied on a scholarship as a day student at St. Paul’s, a London public school noted for its classical studies. In 1899 he won a classical scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge.

Leonard Sidney Woolf was born in London in 1880, the third of ten children of Solomon Rees Sydney and Marie (de Jongh) Woolf. When his father died in 1892, Woolf was sent to board at the Arlington House School, a preparatory school near Brighton. From 1894 to 1899 he studied on a scholarship as a day student at St. Paul’s, a London public school noted for its classical studies. In 1899 he won a classical scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge.

At Cambridge, Woolf became part of a youthful group of intellectuals who were elected to an elite group called ‘The Apostles’. The members of this group included Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Thoby Stephen, John Maynard Keynes and E.M. Forster, who were students, and Bertrand Russell, who was a Fellow. These people eventually formed the core of the Bloomsbury Group.

In 1902 Woolf earned his B.A. degree but stayed on at Cambridge for a fifth year to study for the civil service examination. He left Trinity College in October 1904 to become a cadet in the Ceylon Civil Service. His professional progress was rapid. In August 1908 he was appointed an assistant government agent in the Southern Province, assigned to administer the District of Hambantota.

As part of the Bloomsbury Group, Woolf met Virginia Stephen, Thoby’s sister, and twice proposed marriage to her. He was twice refused. Woolf returned to England in May 1911 for a year’s leave, expecting to return to Ceylon later. In July, however, he proposed to Virginia yet again, and this time she accepted him.

Partly because he chose to marry Virginia and partly because of a growing distaste for colonialism, Woolf resigned from the Ceylon Civil Service early in 1912 (as George Orwell was to do over a decade later). It was at this time that the Bloomsbury Group began to gain momentum as an intellectual and artistic force, and Leonard Woolf was at the centre of it.

In 1913 Woolf published his first novel, The Village and the Jungle, based on his experiences in the colonial service. This was followed by The Wise Virgins in 1914.

Like most other members of the Bloomsbury Group, Woolf was a pacifist and an opponent of Britain’s involvement in the First World War. However, he was spared becoming a conscientious objector, because he was rejected by the military as unfit for duty.

With the outbreak of the war, Woolf turned his attention to politics and sociology. He joined the Labour Party and the Fabian Society and became a regular contributor to New Statesman. In 1916 he wrote International Government which outlined future possibilities for a international agency to enforce peace in the world. The book was incorporated by the British government in its proposals for a League of Nations at Geneva. Woolf was later active in the League of Nations Society and the League of Nations Union.

During the war years Woolf spent a lot of his time caring for his wife Virginia, who was then suffering extreme manic-depression. To provide her with a relaxing hobby they bought a small hand printing press in 1917 and set up the Hogarth Press – named after their home in Richmond. Their first project was a pamphlet containing a story by each of them, printed and bound by themselves.

Other small books followed, written by their friends including T.S. Eliot, Katherine Mansfield and E.M. Forster. Many of the book jackets were designed by Virginia’s sister, the designer and painter Vanessa Bell. Within ten years, the Hogarth Press was a full-scale publishing house and included on its list such seminal works as Eliot’s The Waste Land, Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room and Freud’s Collected Papers, which were translated into English by Julian Strachey, Lytton Strachey’s brother. Leonard Woolf remained the main director of the publishing house from its beginning in 1917 until his death in 1969.

After the war, Leonard Woolf occupied himself more and more with political work. He became editor in 1919 of International Review, and edited the international section of Contemporary Review from 1920 through 1922. He was literary editor of Nation Athenaeum from 1923 to 1930 and joint editor of Political Quarterly from 1931-1959. Woolf also served during the period between the wars as secretary of the Labour Party’s advisory committees on international and colonial questions.

Leonard looked after his wife Virginia through all her periods of depression, right up to the point of her suicide in 1941. They remain a couple who typify the Bloomsbury Group through their personal lives and their prodigious creative output. What is less well known about Leonard Woolf however, is that the latter part of his life was no less radical at a personal level. Love Letters reveals the whole story of this extraordinary episode.

During the Second World War he began an affair with a painter and book illustrator Trekkie Parsons, who was married to a publisher – at that time on active military service. Leonard was 61, Trekkie 39. He wanted her to get a divorce and marry him, but instead she persuaded him to move into the house next door to her in London and she spent the weekends with him at Monk’s House in Rodmell.

When her husband came back from the war, their lives not surprisingly became more complex. She spent the weekends with her husband and the week with Leonard. She took holidays with the two men separately, and acted as hostess for them both. This arrangement worked smoothly for the next twenty-five years.

When Trekkie and Leonard were not together they talked through the post. Trekkie sealed up their correspondence, and it was only opened after her death. Linked by excerpts from her diary, the letters shine with details of daily life: of gardens and glow-worms, books and plays; of Leonard’s publishing and politics; of Trekkie’s struggle to balance her professional and personal life. This remarkable exchange of letters tells the story of two contrasting personalities, their love for one another and their unusual and creative domestic arrangement.

Among Woolf’s most important writings are After the Deluge (1931-51), a multi-volume modern political and social history, and his five-volume autobiography, Sowing (1960), Growing (1961), Beginning Again (1964), Downhill All The Way (1967) and The Journey Not The Arrival Matters (1969). He died August 14, 1969.

Bloomsbury Group – web links

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, featuring designs by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and others.

![]() The Omega Workshops

The Omega Workshops

A brief history of Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops, which had a lasting influence on interior design in post First World War Britain.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War

The Bloomsbury Group and War

An essay on the largely pacifist and internationalist stance taken by Bloomsbury Group members towards the First World War.

![]() Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Mini web site featuring photos, paintings, a timeline, sub-sections on the Omega Workshops, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, and biographical notes.

![]() Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Exhibition of paintings, designs, and ceramics at Toronto University featuring Hogarth Press, Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Quentin Bell, and Stephen Tomlin.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

A rich enthusiast site featuring news of events, exhibitions, new book reviews, relevant links, study resources, and anything related to Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search the texts of all Woolf’s major works, and track down phrases, quotes, and even individual words in their original context.

![]() A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

An annotated description of Clarissa Dalloway’s walk from Westminster to Regent’s Park, with historical updates and a bibliography.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Annotated tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury, including Gordon Square, University College, Bedford Square, Doughty Street, and Tavistock Square.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

News of events, regular bulletins, study materials, publications, and related links. Largely the work of Virginia Woolf specialist Stuart N. Clarke.

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

A charming sound recording of a BBC radio talk broadcast in 1937 – accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephens’ collection of family photographs which became known as the Mausoleum Book, collected at Smith College – Massachusetts.

![]() Bloomsbury at Duke University

Bloomsbury at Duke University

A collection of book jacket covers, Fry’s Twelve Woodcuts, Strachey’s ‘Elizabeth and Essex’.

© Roy Johnson 2000-2014

More on Leonard Woolf

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

He became an Anglican clergyman, but in 1865 renounced his religious beliefs and left the church. In 1869 he married Harriet Thackeray, the daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray. They had a daughter Laura (1870-1945) who developed a form of incurable brain disease and was institutionalised for the majority of her life. When his wife died rather suddenly in 1875 he married Julia Prinsep Jackson, the widow of Herbert Duckworth. She brought with her two sons, George and Gerald, the latter of whom went on to found the Duckworth publishing company.

He became an Anglican clergyman, but in 1865 renounced his religious beliefs and left the church. In 1869 he married Harriet Thackeray, the daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray. They had a daughter Laura (1870-1945) who developed a form of incurable brain disease and was institutionalised for the majority of her life. When his wife died rather suddenly in 1875 he married Julia Prinsep Jackson, the widow of Herbert Duckworth. She brought with her two sons, George and Gerald, the latter of whom went on to found the Duckworth publishing company.

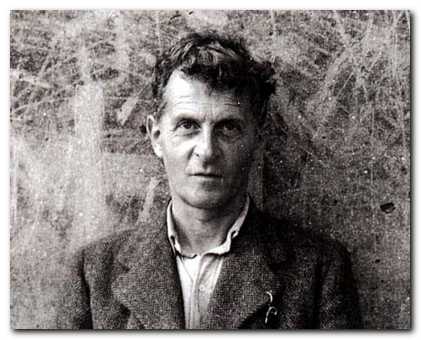

Lytton Strachey (1880-1932) was born at Clapham Common and raised at Lancaster Gate, in central London. He was the eleventh of thirteen children, to General Sir Richard Strachey (an engineer) and his wife Jane Grant. Though he spent some years at boarding schools, including Abbotsholme and Leamington College, he received much of his education at home. His mother took an interest in literature and politics, and Strachey met many of the leading writers and thinkers of the day when they came to visit Lady Strachey. His secondary education was completed at University College in Liverpool where he studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, and English literature and history. It was there that he met and was influenced by Walter Raleigh, a professor of English literature and well known biographer.

Lytton Strachey (1880-1932) was born at Clapham Common and raised at Lancaster Gate, in central London. He was the eleventh of thirteen children, to General Sir Richard Strachey (an engineer) and his wife Jane Grant. Though he spent some years at boarding schools, including Abbotsholme and Leamington College, he received much of his education at home. His mother took an interest in literature and politics, and Strachey met many of the leading writers and thinkers of the day when they came to visit Lady Strachey. His secondary education was completed at University College in Liverpool where he studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, and English literature and history. It was there that he met and was influenced by Walter Raleigh, a professor of English literature and well known biographer.

Strachey’s Letters

Strachey’s Letters Mark Gertler (1896—1939) was born in Spitalfields in London’s East End, the youngest son of Jewish immigrant parents. When he was a year old, the family was forced by extreme poverty back to their native Galicia (Poland). His father travelled to America in search of work, but when this plan failed the family returned to London in 1896. As a boy he showed a marked talent for drawing, and on leaving school in 1906 he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic, which was the first institution in the UK to provide post-school education for working people.

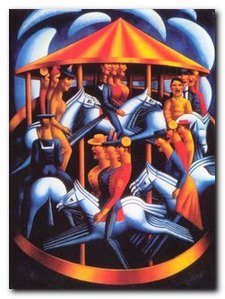

Mark Gertler (1896—1939) was born in Spitalfields in London’s East End, the youngest son of Jewish immigrant parents. When he was a year old, the family was forced by extreme poverty back to their native Galicia (Poland). His father travelled to America in search of work, but when this plan failed the family returned to London in 1896. As a boy he showed a marked talent for drawing, and on leaving school in 1906 he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic, which was the first institution in the UK to provide post-school education for working people. In 1914 he was also taken up by Edward Marsh an art collector who was later to become secretary to Winston Churchill. Even this relationship became difficult, since Gertler was a pacifist, and he disapproved of the system of patronage. He broke off the relationship, and around this time painted what has become his most famous painting – The Merry-Go-Round.

In 1914 he was also taken up by Edward Marsh an art collector who was later to become secretary to Winston Churchill. Even this relationship became difficult, since Gertler was a pacifist, and he disapproved of the system of patronage. He broke off the relationship, and around this time painted what has become his most famous painting – The Merry-Go-Round.

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and