Virginia Woolf’s previously unpublished early works

This is an unusually exciting event for Woolf fans – the first publication of an undiscovered notebook which had been lost for seventy years. Carlyle’s House was written in 1909 when Virginia Woolf was living with her brother Adrian in Fitzroy Square. She was struggling with her first Novel, The Voyage Out and wondering if she would ever be married. It was discovered only a couple of years ago, in Birmingham. The contents of the notebook (which she made herself, by hand) is a series of seven portraits written, as she says of them herself as a sort of artist’s notebook: “the only use of this book is that it shall serve for a sketch book; as an artist fills his pages with scraps and fragments, studies of drapery – legs, arms & noses … so I take up my pen & trace here whatever shapes I happen to have in my head … It is an exercise – training for eye & hand”.

They are an attempt to capture people visually, socially, and even morally. She is trying out the literary techniques which were later to make her famous – capturing the sense of life by a combination of shrewd observation, making imaginative connections between disparate subjects, and sliding effortlessly into philosophic reflections on the topic in question.

They are an attempt to capture people visually, socially, and even morally. She is trying out the literary techniques which were later to make her famous – capturing the sense of life by a combination of shrewd observation, making imaginative connections between disparate subjects, and sliding effortlessly into philosophic reflections on the topic in question.

Some of her observations and commentary are amazingly snooty and condescending. Speaking of the children of Sir George Darwin who she visits in their campus home in Cambridge, she observes:

Margaret is much less formed; but has the same determination to find out the truth for herself, and the same lack of any fine power of discrimination. They enjoy things very much, and fancy that this is due to their superior taste; fancy that in riding about the streets of Cambridge they are building up a theory of life.

Even people’s furniture and choice of paintings and home decor is subject to a scrutiny so close that it becomes like a moral measuring tape:

In the drawing room, the parents’ room, there are prints from Holbein drawings, bad portraits of children, indiscriminate rugs, chairs, Venetian glass, Japanese embroideries: the effect is of subdued colour, and incoherence; there is no regular scheme. In short the room is dull.

As Christopher Reed argues in his authoritative study of this subject, Bloomsbury Rooms, the aesthetics of interior design and furnishing held amongst the Bloomsberries was shot through with a political ideology.

Woolf idolatrists will have to swallow hard to stomach the disgusting anti-semitism of her revealingly entitled piece ‘The Jews’ – for it is in fact a sketch of a single person, Mrs Loeb, who she had visited at Lancaster Gate.

There’s a commendably thorough introduction by Woolf specialist David Bradshaw, full explanatory footnotes, and a foreward by Doris Lessing which is so poorly written that it throws the style of the young Virginia Woolf into high relief. Bradshaw also offers a commentary on each sketch, setting it in context and bringing together all the observations from wide-ranging Woolf scholarship which throw light on these episodes.

This might be the work of the young and untried Woolf, and it might reveal the less-developed and even unappealing side of her character. But we know that she revised many of these attitudes and beliefs in later life. This is a brief collection which enthusiasts will not want to miss.

© Roy Johnson 2005

Virginia Woolf, Carlyle’s House and Other Sketches London: Hesperus, 2003, pp.88, ISBN: 1843910551

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

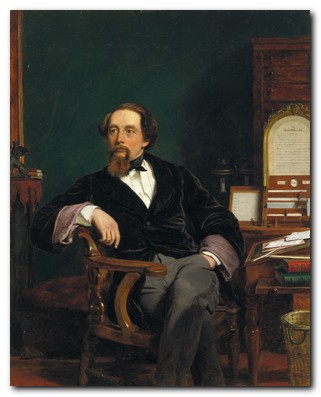

Under Western Eyes 1812. Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth. His father was a clerk in naval pay office: hard-working but unable to live within income. Several brothers and sisters.

1812. Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth. His father was a clerk in naval pay office: hard-working but unable to live within income. Several brothers and sisters. The Oxford Companion to Dickens offers in one volume a lively and authoritative compendium of information aboutDickens: his life, his works, his reputation and his cultural context. In addition to entries on his works, his characters, his friends and places mentioned in his works, it includes extensive information about the age in which he lived and worked.These are the people, events and institutions which provided the context for his work; the houses in which he lived; the countries he visited; the ideas he satirized; the circumstances he responded to; and the culture he participated in. The companion thus provides a synthesis of Dickens studies and an accessible range of information.

The Oxford Companion to Dickens offers in one volume a lively and authoritative compendium of information aboutDickens: his life, his works, his reputation and his cultural context. In addition to entries on his works, his characters, his friends and places mentioned in his works, it includes extensive information about the age in which he lived and worked.These are the people, events and institutions which provided the context for his work; the houses in which he lived; the countries he visited; the ideas he satirized; the circumstances he responded to; and the culture he participated in. The companion thus provides a synthesis of Dickens studies and an accessible range of information.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big popular success, written when he was only twenty-four years old. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These episodes recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big popular success, written when he was only twenty-four years old. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These episodes recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens. Dombey and Son (1847-48) is Dickens’ version of the King Lear story, in which Dombey, the proud and successful head of a shipping company, loses his son, wife, and daughter because of neglect and his lack of sympathy towards them. Even his second wife is driven into the arms of his villainous business manager – with disastrous results. Eventually his empire collapses, and he lives on in tragic desolation – until his daughter Florence returns and finds a way back to his heart. This is the first of Dickens’ great and powerful masterpieces.

Dombey and Son (1847-48) is Dickens’ version of the King Lear story, in which Dombey, the proud and successful head of a shipping company, loses his son, wife, and daughter because of neglect and his lack of sympathy towards them. Even his second wife is driven into the arms of his villainous business manager – with disastrous results. Eventually his empire collapses, and he lives on in tragic desolation – until his daughter Florence returns and finds a way back to his heart. This is the first of Dickens’ great and powerful masterpieces. David Copperfield (1849-50) is a thinly veiled autobiography, of which Dickens said ‘Of all my books, I like this the best’. As a child David suffers the loss of both his father and mother. He endures bullying at school and a life of poverty when he goes to work. The book is packed with memorable characters such as Mr Micawber, the fawning Uriah Heep, and the earth-mother figure Clara Peggotty. The plot involves Dickens’ recurrent topics of thwarted romance, financial insecurity and misdoings, and the terrible force of the legal system which haunted him all his life.

David Copperfield (1849-50) is a thinly veiled autobiography, of which Dickens said ‘Of all my books, I like this the best’. As a child David suffers the loss of both his father and mother. He endures bullying at school and a life of poverty when he goes to work. The book is packed with memorable characters such as Mr Micawber, the fawning Uriah Heep, and the earth-mother figure Clara Peggotty. The plot involves Dickens’ recurrent topics of thwarted romance, financial insecurity and misdoings, and the terrible force of the legal system which haunted him all his life. Bleak House (1852-53) is a powerful critique of the legal system. Characters waiting to gain their inheritance from a will which is the subject of a long-running court case are ruined when the delays and costs of the case swallow up the whole estate. At the same time, Ester Summerson, one of Dickens’ most saintly heroines, is surrounded by mystery regarding her parentage and pressure to marry a man she respects but does not love. Unraveling the mystery results in scandal and deaths. Many memorable characters, including ace sleuth Inspector Bucket; Horace Skimpole a criminally irresponsible house guest; and Krook – the ‘chancellor’ of the rag and bone department, who dies from spontaneous combustion – something which Dickens actually believed could happen.

Bleak House (1852-53) is a powerful critique of the legal system. Characters waiting to gain their inheritance from a will which is the subject of a long-running court case are ruined when the delays and costs of the case swallow up the whole estate. At the same time, Ester Summerson, one of Dickens’ most saintly heroines, is surrounded by mystery regarding her parentage and pressure to marry a man she respects but does not love. Unraveling the mystery results in scandal and deaths. Many memorable characters, including ace sleuth Inspector Bucket; Horace Skimpole a criminally irresponsible house guest; and Krook – the ‘chancellor’ of the rag and bone department, who dies from spontaneous combustion – something which Dickens actually believed could happen. Little Dorrit (1855-57) features Dickens’ recurrent themes of prison, debt, and the negative effects of wealth. William Dorrit and his daughter Amy have been paupers for so long that they actually live in the Marshalsea debtor’s prison. When he is suddenly released because of an inheritance, his place is taken by the middle-aged hero Arthur Clenham when he falls on hard times. Amy is devoted to them both. There is also a murky sub-plot involving doubtful parentage, a mysterious secret, and a villain with two names. Also includes a satirical critique of nineteenth century government bureaucracy in his depiction of the Circumlocution Office. Another of the greatest of Dickens’ works.

Little Dorrit (1855-57) features Dickens’ recurrent themes of prison, debt, and the negative effects of wealth. William Dorrit and his daughter Amy have been paupers for so long that they actually live in the Marshalsea debtor’s prison. When he is suddenly released because of an inheritance, his place is taken by the middle-aged hero Arthur Clenham when he falls on hard times. Amy is devoted to them both. There is also a murky sub-plot involving doubtful parentage, a mysterious secret, and a villain with two names. Also includes a satirical critique of nineteenth century government bureaucracy in his depiction of the Circumlocution Office. Another of the greatest of Dickens’ works. A Tale of Two Cities (1859) was Dickens’ account of the French Revolution – with the story switching between London and Paris. It views the causes and effects of the Revolution from an essentially private point of view, showing how personal experience relates to public history. The characters are fictional, and their political activity is minimal, yet all are drawn towards the Paris of the Terror, and all become caught up in its web of suffering and human sacrifice. The novel features the famous scene in which wastrel barrister Sydney Carton redeems himself by smuggling the hero out of prison and taking his place on the scaffold. The novel ends with the memorable lines: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known.”

A Tale of Two Cities (1859) was Dickens’ account of the French Revolution – with the story switching between London and Paris. It views the causes and effects of the Revolution from an essentially private point of view, showing how personal experience relates to public history. The characters are fictional, and their political activity is minimal, yet all are drawn towards the Paris of the Terror, and all become caught up in its web of suffering and human sacrifice. The novel features the famous scene in which wastrel barrister Sydney Carton redeems himself by smuggling the hero out of prison and taking his place on the scaffold. The novel ends with the memorable lines: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known.” Great Expectations (1860-61) traces the adventures and moral development of the young hero Pip as he rises from humble beginnings in a village blacksmith’s. Eventually, via good connections and a secret benefactor, he becomes a gentleman in fashionable London – but loses his way morally in the process and disowns his family. Fortunately he is surrounded by good and loyal friends who help him to redeem himself. Plenty of drama is provided by a spectacular fire, a strange quasi-sexual attack, and the chase of an escaped convict on the river Thames. There are a number of strange psycho-sexual features to the characters and events, and the novel has two subtly different endings – both adding ambiguity to the love interest between Pip and the beautiful Stella.

Great Expectations (1860-61) traces the adventures and moral development of the young hero Pip as he rises from humble beginnings in a village blacksmith’s. Eventually, via good connections and a secret benefactor, he becomes a gentleman in fashionable London – but loses his way morally in the process and disowns his family. Fortunately he is surrounded by good and loyal friends who help him to redeem himself. Plenty of drama is provided by a spectacular fire, a strange quasi-sexual attack, and the chase of an escaped convict on the river Thames. There are a number of strange psycho-sexual features to the characters and events, and the novel has two subtly different endings – both adding ambiguity to the love interest between Pip and the beautiful Stella. The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory.