writers, artists, and the English sense of place

Romantic Moderns is a major piece of work by a young cultural historian with a free-ranging approach to her subject. It’s a study of a particular strain in English art that Alexandra Harris correctly describes as ‘romantic’, and illustrates as permeating every aspect of cultural life. The period she covers is the late 1930s through to the immediate post-war period. It would be interesting to know if the title of the PhD on which the book is based had a sub-title more specific than the one she provides here – because ‘from Virginia Woolf to John Piper’ is rather wide in scope. After all, Woolf was born in 1882, and Piper lived until 1992 – so that’s a span covering the late Victorian era, two world wars, and the digital age.

Her writing is certainly lively and entertaining. She throws off multiple references that explode like fireworks in almost every paragraph. A consideration of architecture leads to books on buildings, then pictures of buildings, and on to novels that feature them. This cultural enthusiasm is both a strength and a weakness, because whilst the names, titles, and references come thick and fast, it’s sometimes difficult to identify the main point of her argument.

Her writing is certainly lively and entertaining. She throws off multiple references that explode like fireworks in almost every paragraph. A consideration of architecture leads to books on buildings, then pictures of buildings, and on to novels that feature them. This cultural enthusiasm is both a strength and a weakness, because whilst the names, titles, and references come thick and fast, it’s sometimes difficult to identify the main point of her argument.

She’s fizzing with information, but I was sometimes longing for an overview or a generalization. The nearest I spotted was that the people she discusses were all interested in the relationship between ‘art and place’.

She covers an astonishingly wide range of topics. Subjects include English country houses (of the Brideshead type) seascapes, Victorian revivalism, cuisine and gastronomy, the BBC, literary criticism, watercolour painting, music, travel writing, film, landscape gardening, and even the weather.

The artists whose work she discusses include John Betjemann, Eric Ravilious, Cecil Beaton, Edward Bawden, Paul Nash, Benjamin Britten, and Graham Sutherland – and those are just some of the best known. She also deals with a whole host of lesser figures – architects, film-makers, milliners, and interior designers,

It’s a world of country gardens, southern seascapes, churches, and images of a bucolic past. There are no cities, motor cars, iron foundries, or telephones in the iconography of this view of the world. Almost all topographical references come from below a line drawn between the Severn and the Wash. In fact you could be forgiven for thinking that the whole of English culture had been generated within the boundaries of Sussex.

The other worrying and recurrent problem in her approach is that modern English romantic art began much earlier than the late thirties in which she pitches most of her comment. The Georgian poets, water-colourists, and engravers all got under way in the second decade of the century, as a reaction to the brutality of the first world war and a sense that an idyllic past was being lost.

She makes a brave case for pastoral romanticism being an enduring feature in English culture, but it is based on selective (though widespread) evidence, and a nostalgic enthusiasm for a view of the world based on the village green. This can be seen as embarrassingly conservative at a time of Hitler’s extermination of Jews, Stalin’s show trials, and the onset of a fully mechanised second world war.

Her capacity for detail uncovers some interesting points – such as T.S. Eliot exchanging views on blood and soil with anti-Semitic and eugenics-supporting Viscount Lymington. It was but a small step from this to Eliot’s belief in religious notions of ‘continuity’ and nationhood. But the arguments on inherent (almost genetic) national feeling for pastoralism are somewhat dented when she cites the work of Bill Brandt, who was German, and Eliot himself, who came from St Louis, Missouri – not East Coker.

The latter part of the book deals with an unashamed celebration of the glamour and romance of the large English country house, focusing on its presence in the work of Elizabeth Bowen, Osbert Sitwell, and Evelyn Waugh. This doesn’t add a lot more to what has gone before, except to intensify an overt nostalgia for disappearing aristocratic worlds.

It might seem churlish to dwell on the weaknesses of such an enthusiastic and beautifully written study, but I think it would be patronising to a work pitched at this level not to take its arguments seriously enough to question them. Anyway, the book is already a runaway success, and its rich cream pages and high quality colour illustrations are sure to delight anyone who buys it.

© Roy Johnson 2012

Alexandra Harris, Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper, London: Thames and Hudson, 2010, pp.320, ISBN: 0500251711

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

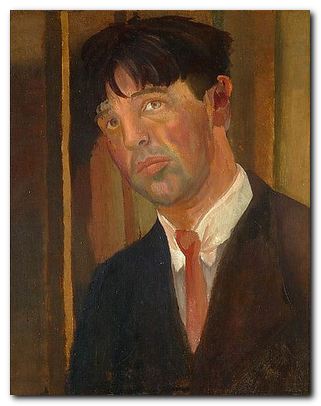

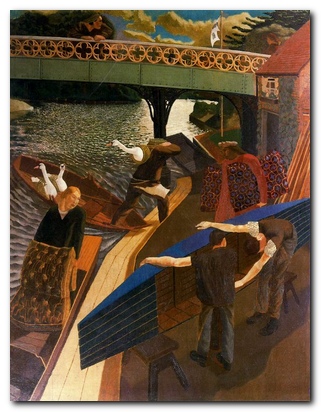

Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) is best known as the sister of

Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) is best known as the sister of

Clive Bell came to visit his sons, and Virginia and Leonard Woolf lived only four miles away. Other guests included

Clive Bell came to visit his sons, and Virginia and Leonard Woolf lived only four miles away. Other guests included