The Hogarth Press 1917—1941

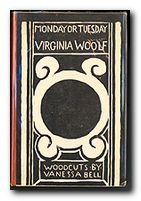

The Hogarth Press was established by Leonard Woolf in 1917 as a therapeutic hobby for his wife Virginia Woolf who was recovering from one of her frequent bouts of ill-health. It was named after Hogarth House in Richmond, London, where they were living at the time. Its first manifestation was a small hand press which they installed on the dining table in their home. They also bought two boxes of type, which was used to hand-set the texts they produced. Working from a sixteen page instructional handbook, they taught themselves how to set the type and print a decent page. What started as an amateur diversion became one of the pillars of European modernism.

The Woolfs have proved endlessly interesting as individuals and as central players in the drama of Bloomsbury. Yet surprisingly little attention has been paid to their achievement as publishers. But with ten years research behind his endeavour, John Willis brings the remarkable story of their success as publishers to life. You might expect a book of this kind to be not much more than a long descriptive catalogue of publications, but in fact he generates interesting thumbnail sketches of Hogarth’s authors, which brings both them and the books they wrote into sharp focus

The Woolfs have proved endlessly interesting as individuals and as central players in the drama of Bloomsbury. Yet surprisingly little attention has been paid to their achievement as publishers. But with ten years research behind his endeavour, John Willis brings the remarkable story of their success as publishers to life. You might expect a book of this kind to be not much more than a long descriptive catalogue of publications, but in fact he generates interesting thumbnail sketches of Hogarth’s authors, which brings both them and the books they wrote into sharp focus

He also follows the development of many of its best-selling titles, and there’s a full account of the social and cultural development of the press, as well as the minute details of its finances which Leonard Woolf left behind as a legacy of his administrative skills and background.

The press is best known for its fiction, but it also ventured into poetry – supported by a £200 a year subsidy from Dorothy Wellesley. But despite attracting many of the brightest young talents of the inter-war years, none of these publications broke even. The whole enterprise was kept afloat by its best-selling stars, who just happened to be the one-time lovers Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville West.

Leonard Woolf is rightly famous for his shrewd commercial judgements and his fanatical bookkeeping, yet the press also took on an amazing range of authors – from an unknown sixteen year old girl (Joan Adeney Easdale) to the ‘working class’ John Hampson (Saturday Night at the Greyhound) and arch modernists such as Gertrude Stein and Rainer Maria Rilke (The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge).

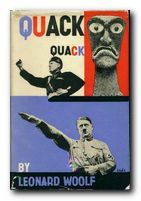

What’s not so well known is that the Hogarth Press published a great deal on politics – from polemical essays on current affairs to substantial works of political and economic philosophy, particularly anti-imperialism and the promotion of internationalism, which was of particular interest to Leonard Woolf. A measure of his astuteness as a businessman was his publication of Mussolini’s article ‘The Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism’ in 1933.

The Maurice Dobbs and the Sidney Webbs of this era published books and pamphlets arguing that Soviet communism offered a positive alternative to the nationalism and imperialism of the European powers which had led to the horrors of the First World War.

Their fundamental error, now more easily observed with the benefit of hindsight, is that they took all the data for their analysis directly from the Soviet regime itself, which we now know was based on lies, falsehoods, corruption, and deceit. They were bamboozled, and didn’t check their facts. Few escaped the God that Failed embarrassment – but Leonard Woolf was one of them, and he deserves to be more highly regarded because of it.

It’s interesting to note that many of the same issues which are being debated at the end of the first century of the twenty-first century were alive eighty years ago – educational reforms, anti-Imperialism, international finance, unemployment, and capitalism in crisis.

Willis’s account also features the strained and often difficult relationships which were created when Leonard Woolf took on assistants and partners in the firm – the best known of whom was John Lehmann, who had two periods of tenure. The partnership approach foundered because Leonard insisted on sticking to his independent commercial practises, and in the end he was proved right.

He was also right in his judgement that the English-speaking world was ready for psycho-analysis and the works of Freud. He took the bold step of publishing translations (some by friends, James and Alix Strachey) of the International Psycho-Analytic Library, as well as Freud’s Collected Papers.

This is a fascinating work which embraces literature, poetry, politics, feminism, international affairs, the mechanics of publishing, and a general account of cultural history in UK of the inter-war years – sometimes referred to as ‘the long weekend’.

There are three ideal audiences for this book: fans of Bloomsbury who want to know about one of its most productive enterprises; bibliophiles who are interested in a company which produced fine objects which were culturally significant but still made money; and cultural historians who might wish to ponder the significance of an enterprise which started out as a table-top hobby and became a major national cultural force.

© Roy Johnson 2005

J.H. Willis Jr, Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers: Hogarth Press, 1917-41, London: University of Virginia Press, 1992, pp.451, ISBN: 0813913616

More on Leonard Woolf

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Many of the book jackets were designed by Virginia’s sister, the designer and painter

Many of the book jackets were designed by Virginia’s sister, the designer and painter  Virginia Woolf is now well known for her love-affair with fellow writer

Virginia Woolf is now well known for her love-affair with fellow writer  As their enterprise became more successful and the volume of business grew, they felt they needed more help. A succession of younger men were employed to help run the Press – many of them aspirant young writers themselves. Amongst them was Richard Kennedy, a sixteen year old boy, who recorded his very amusing memories of the experience in

As their enterprise became more successful and the volume of business grew, they felt they needed more help. A succession of younger men were employed to help run the Press – many of them aspirant young writers themselves. Amongst them was Richard Kennedy, a sixteen year old boy, who recorded his very amusing memories of the experience in  Curiously enough, as John Lehmann records in his account of these years, these disasters proved to be a benefit to the press. Its editorial offices and stock rooms were in the same building as its printers, and both were a long way away from London, where other publishers were suffering losses to their inventory as a result of air raids during the war. The odd thing is that despite paper rationing, sales rose, because of general shortages: “Books that in peacetime, when there was an abundance of choice, would have sold only a few copies every month, were snapped up the moment they arrived in the shops.”

Curiously enough, as John Lehmann records in his account of these years, these disasters proved to be a benefit to the press. Its editorial offices and stock rooms were in the same building as its printers, and both were a long way away from London, where other publishers were suffering losses to their inventory as a result of air raids during the war. The odd thing is that despite paper rationing, sales rose, because of general shortages: “Books that in peacetime, when there was an abundance of choice, would have sold only a few copies every month, were snapped up the moment they arrived in the shops.” Disagreements rumbled on until after the war had ended. When the final split between them came about in 1946, Leonard solved the financial problem of raising £3,000 to keep the company afloat by persuading fellow publisher Ian Parsons of Chatto and Windus to buy out John Lehmann’s share. The Hogarth Press became a limited company within Chatto & Windus, on the strict understanding that Leonard Woolf had a controlling decision on what the Hogarth Press published.

Disagreements rumbled on until after the war had ended. When the final split between them came about in 1946, Leonard solved the financial problem of raising £3,000 to keep the company afloat by persuading fellow publisher Ian Parsons of Chatto and Windus to buy out John Lehmann’s share. The Hogarth Press became a limited company within Chatto & Windus, on the strict understanding that Leonard Woolf had a controlling decision on what the Hogarth Press published.

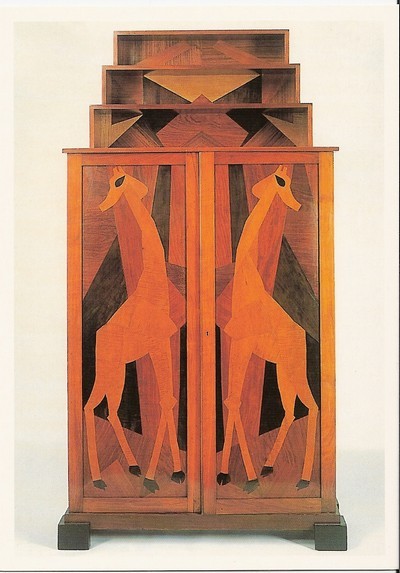

It opened in 1913 at the worst possible time in commercial terms, at 33 Fitzroy Square in the heart of Bloomsbury.

It opened in 1913 at the worst possible time in commercial terms, at 33 Fitzroy Square in the heart of Bloomsbury.  At the launch of the project, artist and writer Wyndham Lewis was also a member; but he quickly split away from the group in a dispute over Omega’s contribution to the Ideal Homes Exhibition. Lewis circulated a letter to all shareholders, making accusations against the company and Roger Fry in particular, and pouring scorn on the products of Omega and its ideology. This subsequently led to his establishing the rival Vorticist movement and the publication in 1916 of its two-issue house magazine, BLAST.

At the launch of the project, artist and writer Wyndham Lewis was also a member; but he quickly split away from the group in a dispute over Omega’s contribution to the Ideal Homes Exhibition. Lewis circulated a letter to all shareholders, making accusations against the company and Roger Fry in particular, and pouring scorn on the products of Omega and its ideology. This subsequently led to his establishing the rival Vorticist movement and the publication in 1916 of its two-issue house magazine, BLAST.

Studying Fiction

Studying Fiction