tutorial, critical commentary, plot, and study resources

Roderick Hudson (1875) was Henry James’s second novel, and the first to bring him a popular success. It initially appeared in twelve monthly issues of the Atlantic Monthly, for which he was paid $100 per instalment. Later in 1879 it was published in three volumes in the UK. This was a common format for full length novels at the time. His first novel had been Watch and Ward published as a serial in 1871, but James virtually disowned the book later in life, and it was not included in the New York edition of his collected works published in 1912.

Roderick Hudson – critical commentary

Biography

Henry James’s grandfather was a relatively poor Irish immigrant who though sheer effort and economic enterprise became one of America’s first millionaires, second only to Jacob Astor. Henry James senior (his son) disdained commerce and became a religious philosopher, yet lived on the proceeds of his father’s labours.

This enabled Henry James senior and his family to live in relative luxury, oscillating between Europe and America. His own two sons William and Henry James were raised in a social expectation that they did not have to earn their livings, and both of them dabbled with the idea of becoming artists – before William eventually studied medicine and Henry began supplementing his private income by journalism and writing novels.

There is therefore a strong connection between Henry James’s own experience of a richly privileged lifestyle and that of his characters in Roderick Hudson who move around the European cities of the Grand Tour supported entirely by the wealth of Rowland Mallet, his principal character . Mallet has inherited his wealth from a puritan father, and he appears to be no worse off financially at the end of his two year experiment than he was at the beginning.

Mallet has no ambition at the outset of the novel other than to collect good quality paintings and donate them to an American museum – something for which he is criticised by his cousin Cecilia and by Mary Garland. He later changes this ambition to that of ‘cultivating’ the talent he sees in Roderick Hudson.

The artist

James makes very little attempt to give substance and credibility to Roderick’s efforts as a sculptor. There is no detail of what might be involved in manipulating clay or chiselling marble – and Roderick’s meteoric rise to success in such a short time puts a strain on the reader’s credulity.

We know that James studied painting, and that he spent time amongst expatriate American artists during the time he lived in Rome – but there is no convincing sense of the physical or practical issues involved in being a three dimensional artist, even though we are led to believe that Roderick produces two large-scale figures (Adam and Eve at almost his first attempt.

The significance of this weakness in characterisation is that it reinforces the notion that James was not genuinely interested in developing what might be called ‘a portrait of the artist’, whereas he did pursue his interest in the relationship between the two men to its bitter end.

Location

The geographic dislocations (particularly towards the end of this over-long novel) undermine its coherence. The narrative begins in America, then moves to Rome. But later the action switches from Rome to two locations in Florence, and then finally for no convincing reason to Switzerland.

Since the main focus of interest is on the psychological relationships between the principal characters (Rowland, Roderick, Mary, and Christina) there is no meaningful connection between the drama of their relationships and the locations in which they are acted out.

The key points of the drama are that Christina is threatened with the revelation that Giacosa is her natural father, as a result of which she reluctantly marries the Prince. Because of this, Rodericks’ romantic aspirations and artistic confidence are shattered. These events could take place anywhere, and the only justification for the climax occurring in Switzerland is to give Roderick a mountain cliff from which to fall to his death.

Intertextuality

Intertextuality is a term used to describe one text referring to or alluding to another. This can happen by allusion, pastiche, parody. or direct quotation. James creates a particularly interesting form of intertextuality in Roderick Hudson by creating characters who will appear in more than one of his future novels.

Christina Light first appears in Roderick Hudson as the beautiful but disillusioned offspring of a fairly unscrupulous mother who is trying to locate a rich husband for her daughter. But then she reappears as a major character in the later novel The Princess Casamassima (1885) performing a very different role.

Between the end of Roderick Hudson and the beginning of The Princess Casamassima Christina leaves her husband and takes up the cause of revolutionaries in London. She is accompanied by the same trusty advisor Madame Grandoni who continues to support her and acts as a link between Christina and the hero of the later novel, Hyacinth Robinson. Her husband the Prince Casamassima also reappears in the later novel – in hot pursuit of his wife, seeking a reconciliation – which she refuses to effect.

A smaller example is the character of Gloriani – the rather sceptical and pragmatic sculptor who creates works which will appeal to popular public taste rather than something of lasting value. Gloriani appears in Roderick Hudson as the embodiment of an alternative artistic value to Roderick himself, who wishes to be honest to a higher system of values.

Gloriani also appears in the later novel The Ambassadors (1903) filling a similar role – and commentators have observed that his character is based on the controversial American painter James McNeil Whistler.

Psycho-interpretation

Whilst the two principal male characters appear to be in parallel amorous relationships with the two principal females, Mary and Christina, most readers will have no difficulty in recognising that Roderick and Rowland spend the whole of the novel locked into a very emotional relationship – with each other.

Rowland is the older, more experienced figure, and Roderick being younger, is a character to whom Rowland is very attracted. His initial interest is triggered by the statuette of a young boy that Roderick creates – a youth drinking from a cup. Rowland then pays for Roderick’s two year experiences in Europe, and even gives financial support to his mother Mrs Hudson and her companion Mary Garland. He pays off Roderick’s debts, indulges his every whim, and stays loyal to him right through to the bitter and tragic end, despite the many emotional lover-like spats they generate between themselves.

It is often observed that when two men are in love with the same woman, this is a psychological clue that they are (perhaps unconsciously) attracted to each other. But in Roderick Hudson Rowland and Roderick are not just attracted to one woman, but to two.

At the start of the novel Rowland is intrigued by the plain but intelligent Mary Garland, but it is Roderick who has proposed marriage to her, and been accepted. In the two years of their sojourn in Europe, Rowland is increasingly attracted to the idea of Mary and he feels mildly annoyed with Roderick’s neglect of his duties towards his fianceé.

But when the beautiful and enigmatic Christina Light appears, Roderick’s affections switch completely from one woman to the other. Rowland thinks this might make Mary available, but by far the greater part of his emotional energy is devoted to his pursuit of Roderick.

The submerged theme of homosexuality was probably created unconsciously on Henry James’s part – just as his two fictional characters are not aware of it themselves. But it is a critical stance worth taking to the novel – because of its frequent recurrence in the rest of James’s oeuvre. There are countless other works (particularly the tales) that deal with this theme and its many variations – the fear of marriage (The Path of Duty) the threat of inheritance (Owen Wingrave) and the missed opportunity (The Beast in the Jungle).

The submerged theme could also have a bearing on the rather unsatisfactory conclusion to the novel. Roderick may well be disappointed by Christina’s choosing to marry the Prince [he does not know that her hand has been forced] but his death in what appears to be almost a suicide does not seem persuasive. However, it might be one or even the only way for James to draw to a close the relationship between the two men.

Roderick Hudson – study resources

![]() Roderick Hudson – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Roderick Hudson – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Roderick Hudson – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Roderick Hudson – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Roderick Hudson – Kindle edition

Roderick Hudson – Kindle edition

![]() Roderick Hudson – eBooks at Project Gutenberg

Roderick Hudson – eBooks at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() The Essential Henry James Collection – Kindle edition (40 works)

The Essential Henry James Collection – Kindle edition (40 works)

![]() The Prefaces of Henry James – Introductions to his tales and novels

The Prefaces of Henry James – Introductions to his tales and novels

![]() Roderick Hudson – Notes on editions (Library of America)

Roderick Hudson – Notes on editions (Library of America)

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Roderick Hudson – chapter summaries

I. Rowland Mallet is a rich young American bachelor who is preparing to go to Europe. He visits his cousin Cecilia who chides him about his lack of purpose and ambition. He claims he will collect paintings and donate them to a museum. Cecilia shows him an impressive statuette made by her friend Roderick Hudson.

II. Next day Rowland meets Roderick, who is a young and nervous Virginian. He is working with no enthusiasm in a law office. Rowland feels attracted to him and offers to take him to Rome to become a sculptor.

III. Roderick’s plan is resented by his mother, and Cecilia regrets his going to Rome. Rowland reassures Mrs Hudson of his good intentions and his belief in Roderick’s talent, but Mr Striker and Mary Garland remain sceptical.

IV. Rowland becomes more interested in Mary Garland. At a picnic she chides him for having no occupation.. When they set off for Europe, Roderick suddenly reveals to Rowland that he is engaged to Mary.

V. Three months later Roderick suddenly feels he is a changed man. He is spending money and absorbing impressions at a very fast rate. He is suddenly inspired after seeing a very attractive girl in a garden. He becomes an active participant in Rome’s social life; he completes a statue of Adam then three months later a complementaryEve.

VI. Rowland tries to overcome his feelings for Mary Garland by considering Augusta Blanchard. At a party, Roderick announces boastfully his intention to create great works of Art. The sceptic Gloriani thinks he will not sustain his early promise, and Madame Grandoni warns him against bohemianism. Shortly afterwards, Roderick runs out of inspiration. He stays alone in Switzerland and Germany for the summer, leaving Rowland to visit England.

VII. In England Rowland receives letters from Cecilia and Mary Garland, and from Roderick who is in Baden-Baden, losing money gambling. Rowland pays his debts and they meet in Geneva, where Roderick confesses that he is susceptible to attractive women. Back in Rome Roderick returns to work but feels that inspiration has deserted him. Their fellow American artist Sam Singleton has spent the entire summer in Italy improving his art, and is very happy.

VIII. Roderick and Rowland are visited by the eccentric Mrs Light and her daughter Christina, who is beautiful but disdainful. Roderick offers to make a sculpture of her. Rowland discovers from Madame Grandoni that Mrs Light is an adventuress with a chequered past who is searching for a rich husband for her daughter. When he goes to visit them, he discovers Roderick at work on the sculpture

IX. Roderick wishes to stay in Rome indefinitely, and thinks to send for Mary Garland and his mother to join him there. But meanwhile he is drawing closer to Christina Light. The completed bust of her is a big success. Rowland is sceptical about Christina, and is mildly envious of Roderick’s connection with Mary.

X. Augusta Blanchard introduces Roderick to Mr Leavenworth, a rich American businessman who wishes to commission a statue for his library. Christina complains that her mother is immoral and that she is disgusted by her conspicuous husband-hunting. She quizzes Rowland about Roderick, and he reveals to her that he is engaged to Mary Garland.

XI. Roderick is angry about this revelation and accuses Rowland of trying to control him. The two of them argue about Christina Light. Roderick falls into artistic doldrums and fears that his genius has left him. Rowland tries to encourage him, but to no avail.

XII. They are joined by Mrs Light, Christina, and Prince Casamassima. A picnic is arranged, after which Christina flirts with Roderick, which makes the Prince jealous, because he is in love with her. Giacosa reveals to Rowland that the Prince is very rich and very proud of his family’s name and his title. Mrs Light complains to Rowland about the sacrifices she has made in her ambition for Christina.

XIII. In the Colosseum Rowland overhears Christina reproaching Roderick for being weak and indecisive. Roderick proposes to show off by climbing dangerously to retrieve a flower for her, but is stopped by Rowland. Socially, Roderick makes few friends, he becomes more and more jaded, and slides into bohemian habits.

XIV. Rowland meets Christina in an old church. They discuss Roderick, and Rowland asks her to leave Roderick alone if she has no intention of marrying him. He appeals to her to make a sacrifice as a gesture of generosity and good will. A few days later she claims to have done so.

XV. Rowland writes to Cecilia in despair about the failure of his project with Roderick. He is exasperated by his friend’s mercurial temperament. Leavenworth breaks the news of Christina’s engagement to the Prince. Roderick refuses to complete his commission, and then argues with Rowland and will not accept his advice.

XVI. Rowland escapes alone to Florence, leaving Roderick still occupied with Christina. There he broods on Mary Garland and Roderick’s possible downfall. After a quasi-religious experience he returns to Rome and suggests that Mrs Hudson and Mary Garland should join them there. Roderick finally agrees – but he fails to meet them when they arrive.

XVII. Mary has matured in the two years they have been apart. There is tension between Roderick and his two guests. Next day they meet Christina in St Peter’s, where Roderick reveals that Christina may not be marrying Prince Casamassima after all.

XVIII. Mrs Hudson sits for a newly inspired Roderick in the mornings, leaving Rowland free to show Mary Garland around Rome. They challenge each other regarding art and nationalism, and she begins to take a serious interest in culture. Roderick and Rowland do not discuss the situation in which they find themselves.

XIX. Roderick finishes the sculpture (which is a success) but tells Rowland he is bored by the presence of his mother and Mary Garland. Rowland implores him to leave Rome with Mary at once and repair their relationship, but Roderick wishes to stay for Christina’s wedding. Gloriani thinks Roderick is truly talented. Christina arrives uninvited to Madame Grandoni’s party to inspect Mary Garland.

XX. Mary Garland does not like Christina and is suspicious of her motives. Giacosa pleads with Rowland to help Mrs Light, because Christina has suddenly called off her engagement to the Prince. Roderick has banished his mother and Mary for a week so that he can bask in the pleasure Christina’s news gives him. Mrs Light pleads with Rowland to remonstrate with Christina – but it is Giacosa’s additional supplication that moves him. He speaks to Christina, who tells him that she does not love the Prince..

XXI. Next day Rowland says goodbye to Sam Singleton who is returning to America, then he learns from Madame Gardoni that Christina married the Prince early that morning. They conclude that Giacosa is Christina’s true father, and her mother has used this information to force her hand. Roderick tells his mother and Mary that he is a failure. He also tells his mother about his infatuation with Christina and that he is bankrupt. Rowland arranges for them to leave Rome and stay at a villa in Florence.

XXII. At the villa in Florence the general mood of the party continues to be one of depression. Roderick does no work, and Mary is unhappy. Roderick says he might as well be a failure in America, but Rowland persuades him to stay in Europe for another year.

XXIII. The party leave Italy and travel to Switzerland. Roderick expresses his total despair to Rowland, who wonders if Mary will become available for him. Roderick claims he no longer cares for her, or for anyone else. Rowland makes subtle overtures to Mary, but she rebuffs him.

XXIV. Roderick feels bitter about Christina because he thinks she betrayed him. Sam Singleton turns up and is a model of artistic industry. Rowland meets Christina and the Prince on an excursion. She insists to him that she was sincere about her feelings for Roderick, but was forced into her marriage. She also says she is going to live recklessly.

XXV. Roderick asks Rowland to lend him money to go to Interlaken to meet Christina. She has fired up his desire and his will to live again. When Rowland is hesitant, he asks his mother and Mary, but they have no money. The two men argue about their behaviour and motivation, and Rowland reveals that he has been in love with Mary for two years.

XXVI. Roderick goes off alone into the mountains. There is a ferocious thunderstorm. Next day when he has still not returned, Rowland and Sam Singleton find his dead body at the bottom of a cliff from which he has fallen. The principals later return to America.

© Roy Johnson 2015

Roderick Hudson – principal characters

| Rowland Mallet | a rich New England bachelor |

| Cecilia | his cousin, a young widow |

| Bessie | her daughter |

| Roderick Hudson | a young Virginian artist |

| Mrs Hudson | Roderick’s widowed mother |

| Miss Mary Garland | a distant cousin |

| Barnaby Striker | Mrs Hudson’s lawyer |

| Stephen Hudson | Roderick’s elder brother, killed in the Civil War |

| Gloriani | a sceptical Franco-American sculptor (who also appears in The Ambassadors) |

| Sam Singleton | modest young American painter |

| Miss Augusta Blanchard | a rich and attractive American painter |

| Madame Grandoni | ugly old German wise woman |

| Mrs Light | an eccentric dowager American adventuress |

| Christina Light | her very beautiful daughter (who also appears in The Princess Casamassima |

| Cavaliere Giuseppe Giacosa | an Italian friend of Mrs Light and father of Christina |

| Prince Casamassima | an ugly Neapolitan nobleman |

| Mr Leavenworth | rich American industrialist |

| Assunta | Christina’s maid |

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James, London: Macmillan, 1984.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James, London: Macmillan, 1984.

![]() Martha Banta (ed), New Essays on The American, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987

Martha Banta (ed), New Essays on The American, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, London: Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, London: Macmillan, 2010.

![]() Oscar Cargill, The Novels of Henry James, New York: Macmillan, 1961.

Oscar Cargill, The Novels of Henry James, New York: Macmillan, 1961.

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other work by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on Henry James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth The Reef

The Reef

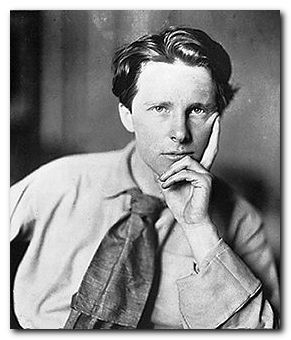

Rupert Brooke (1887—1915) was only ever on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group – but he was well acquainted with its central figures, such as

Rupert Brooke (1887—1915) was only ever on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group – but he was well acquainted with its central figures, such as

C=criticism

C=criticism The Complete Critical Guide to Samuel Beckett

The Complete Critical Guide to Samuel Beckett Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life

Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life The Cambridge Companion to Beckett

The Cambridge Companion to Beckett Murphy is Samuel Beckett’s first novel, published in 1938. It was written in English, unlike many of his later works which were written in French then translated into English. It is the story of a work-shy man, wandering adrift in London, who believes that human desire can never be satisfied. He seeks to withdraw from life into a state of what he sees as catatonic bliss. Murphy’s fiancée Celia tries to humanise him by finding him a job working as a nurse in a mental institution, but he sees the insanity of the patients an attractive alternative to his conscious existence from which he cannot escape.

Murphy is Samuel Beckett’s first novel, published in 1938. It was written in English, unlike many of his later works which were written in French then translated into English. It is the story of a work-shy man, wandering adrift in London, who believes that human desire can never be satisfied. He seeks to withdraw from life into a state of what he sees as catatonic bliss. Murphy’s fiancée Celia tries to humanise him by finding him a job working as a nurse in a mental institution, but he sees the insanity of the patients an attractive alternative to his conscious existence from which he cannot escape. Watt Beckett’s second novel was written during World War Two (1942-1944), while he was hiding from the Gestapo in Provence in southern France. It was first published in English in 1953 and tells a semi-incoherent story of Watt’s journey to become the manservant of a Mr Knott, and his struggle to understand the house they live in. It’s written with some of Beckett’s characteristically deadpan humour and quasi-philosophic jokes. He also uses deliberately unidiomatic language and pokes fun at contemporary figures and institutions. Watt has previously appeared in editions that are littered with major and minor errors. The new Faber edition offers for the first time a corrected text based on a scholarly appraisal of the manuscripts and their textual history.

Watt Beckett’s second novel was written during World War Two (1942-1944), while he was hiding from the Gestapo in Provence in southern France. It was first published in English in 1953 and tells a semi-incoherent story of Watt’s journey to become the manservant of a Mr Knott, and his struggle to understand the house they live in. It’s written with some of Beckett’s characteristically deadpan humour and quasi-philosophic jokes. He also uses deliberately unidiomatic language and pokes fun at contemporary figures and institutions. Watt has previously appeared in editions that are littered with major and minor errors. The new Faber edition offers for the first time a corrected text based on a scholarly appraisal of the manuscripts and their textual history. The Trilogy This is the famous trilogy that is generally regarded as the pinnacle of Beckett’s work as an experimental novelist. He was pushing the developments of modernism, existentialism, and absurdism as far as they would go. The three novels follow the bleak logic of Beckett’s move away from movement and life, towards stasis and death. Molloy (1951) is set in an indeterminate place and comprises the inner monologues of Molloy and a private detective called Moran. Both live in a state of semi-absurdity and seem almost to merge into the same person as they lose bodily mobility and end up using crutches. Malone Dies (1951) is the story of an old man who is confined to bed in a hospital or an asylum (he is not sure which). All notions of conventional plot or logical sequences of events are abandoned. The narrative is merely Malone’s obsession with the trivia of his existence, stripped of all physical effects except an exercise book and a pencil that is getting shorter and shorter. The Unnameable (1953) takes these experiments in prose fiction one stage further. It concerns a person with no name who lives under an old tarpaulin sheet. He is not even sure if he is dead or alive – and neither are we.

The Trilogy This is the famous trilogy that is generally regarded as the pinnacle of Beckett’s work as an experimental novelist. He was pushing the developments of modernism, existentialism, and absurdism as far as they would go. The three novels follow the bleak logic of Beckett’s move away from movement and life, towards stasis and death. Molloy (1951) is set in an indeterminate place and comprises the inner monologues of Molloy and a private detective called Moran. Both live in a state of semi-absurdity and seem almost to merge into the same person as they lose bodily mobility and end up using crutches. Malone Dies (1951) is the story of an old man who is confined to bed in a hospital or an asylum (he is not sure which). All notions of conventional plot or logical sequences of events are abandoned. The narrative is merely Malone’s obsession with the trivia of his existence, stripped of all physical effects except an exercise book and a pencil that is getting shorter and shorter. The Unnameable (1953) takes these experiments in prose fiction one stage further. It concerns a person with no name who lives under an old tarpaulin sheet. He is not even sure if he is dead or alive – and neither are we. The Expelled This collection of four stories or nouvelles represents work which dates from 1945, though they were all published much later, in French and then in English. Full contents: The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, and First Love. All the stories make use of a first-person narrator, and exploit its potential for expressing the frailties of human memory, the inability to distinguish the past from the present, and even a profound doubt concerning the purpose of life itself. The stories document the human condition of an unstoppable progress towards death.

The Expelled This collection of four stories or nouvelles represents work which dates from 1945, though they were all published much later, in French and then in English. Full contents: The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, and First Love. All the stories make use of a first-person narrator, and exploit its potential for expressing the frailties of human memory, the inability to distinguish the past from the present, and even a profound doubt concerning the purpose of life itself. The stories document the human condition of an unstoppable progress towards death. How It Is Published in French in 1961, and in English in 1964, this presents a novel in three parts, written in short paragraphs, which tell of a narrator lying in the dark, in the mud, repeating his life as he hears it uttered – or remembered – by another voice. Told from within, from the dark, the story is tirelessly and intimately explicit about the feelings that pervade his world, but fragmentary and vague about all else therein or beyond. The novel counts for many readers as Beckett’s greatest accomplishment in the prose narrative form. It is also his most challenging work, both stylistically and for the radical pessimism of its vision, which continues the themes of reduced circumstance, of another life before the present, and the self-appraising search for an essential self.

How It Is Published in French in 1961, and in English in 1964, this presents a novel in three parts, written in short paragraphs, which tell of a narrator lying in the dark, in the mud, repeating his life as he hears it uttered – or remembered – by another voice. Told from within, from the dark, the story is tirelessly and intimately explicit about the feelings that pervade his world, but fragmentary and vague about all else therein or beyond. The novel counts for many readers as Beckett’s greatest accomplishment in the prose narrative form. It is also his most challenging work, both stylistically and for the radical pessimism of its vision, which continues the themes of reduced circumstance, of another life before the present, and the self-appraising search for an essential self. Company These four last prose fictions span the final decade of Beckett’s life. In the title sytory a solitary listener lying in darkness calls up images from a past life. Ill Seen Ill Said is a meditation on an old woman living out her final days in an isolated cottage, watched over by a dozen mysterious sentinels. In Worstward Ho, a breathless speaker unravels the sense of life, acting out the repeated injunction to ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ Stirrings Still was published in the Guardian a few months before Beckett’s death in 1989. It is his last prose work and testament. The Faber edition also includes several short prose texts (Heard in the Dark I & II, One Evening, The Way, Ceiling) which represent works in progress or fragments composed around the same time as his final writing.

Company These four last prose fictions span the final decade of Beckett’s life. In the title sytory a solitary listener lying in darkness calls up images from a past life. Ill Seen Ill Said is a meditation on an old woman living out her final days in an isolated cottage, watched over by a dozen mysterious sentinels. In Worstward Ho, a breathless speaker unravels the sense of life, acting out the repeated injunction to ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ Stirrings Still was published in the Guardian a few months before Beckett’s death in 1989. It is his last prose work and testament. The Faber edition also includes several short prose texts (Heard in the Dark I & II, One Evening, The Way, Ceiling) which represent works in progress or fragments composed around the same time as his final writing. Works for Radio

Works for Radio Complete Dramatic Works This one-volume compendium contains all of Beckett’s dramatic texts written between 1955 and 1984. It includes both the major dramatic works and the shorter and more compressed texts he created for the stage and for radio. Full contents: Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Happy Days, All That Fall, Acts Without Words, Krapp’s Last Tape, Roughs for the Theatre, Embers, Roughs for the Radio, Words and Music, Cascando, Play, Film, The Old Tune, Come and Go, Eh Joe, Breath, Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio,…but the clouds…, A Piece of Monologue, Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Quad, Catastrophe, Nacht und Traume, What Where.

Complete Dramatic Works This one-volume compendium contains all of Beckett’s dramatic texts written between 1955 and 1984. It includes both the major dramatic works and the shorter and more compressed texts he created for the stage and for radio. Full contents: Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Happy Days, All That Fall, Acts Without Words, Krapp’s Last Tape, Roughs for the Theatre, Embers, Roughs for the Radio, Words and Music, Cascando, Play, Film, The Old Tune, Come and Go, Eh Joe, Breath, Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio,…but the clouds…, A Piece of Monologue, Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Quad, Catastrophe, Nacht und Traume, What Where. Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life gives a short account of Beckett’s little-known private life in a book which is packed with rare photographs and shots of his stage productions. The life is quite surprising: a priviledged upbringing, with talented academic prospects which he abandonded for a bohemian life. Fighting with the Maquis during the war. Little artistic success, but lots of relationships with women – and then the big breakthrough with Waiting for Godot. This is a stunning little book.

Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life gives a short account of Beckett’s little-known private life in a book which is packed with rare photographs and shots of his stage productions. The life is quite surprising: a priviledged upbringing, with talented academic prospects which he abandonded for a bohemian life. Fighting with the Maquis during the war. Little artistic success, but lots of relationships with women – and then the big breakthrough with Waiting for Godot. This is a stunning little book.