annotated bibliography of criticism and comment

Vladimir Nabokov criticism is a bibliography of critical comment on Nabokov and his works, with details of each publication and a brief description of its contents. The details include active web links to Amazon where you can buy the books, often in a variety of formats – new, used, and as Kindle eBooks. The listings are arranged in alphabetical order of author.

The list includes new books and older publications which may now be considered rare. It also includes print-on-demand or Kindle versions of older texts which are much cheaper than the original. Others (including some new books) are often sold off at rock bottom prices. Whilst compiling these listings I bought a copy of Jayne Grayson’s Vladimir Nabokov – Illustrated life for one pound.

Nabokov’s Otherworld – Vladimir E. Alexadrov, Princeton University Press, 2014. This book shows that behind his ironic manipulation of narrative and his puzzle-like treatment of detail there lies an aesthetic rooted in his intuition of a transcendent realm and in his consequent redefinition of ‘nature’ and ‘artifice’ as synonyms.

The Garland Companion to Vladimir Nabokov – Vladimir E. Alexandrov, 2014. Reprint of a 1995 collection of articles and critical essays on Nabokov’s work, plus background reading to his life and suggestions for further reading.

Nabokov’s Dark Cinema – Alfred Appel, Oxford University Press, 1975.

Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years – Brian Boyd, Princeton University Press, 2001. This is the first volume of the definitive biography.

Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years – Brian Boyd, Princeton University Press, 1993. This is the second volume of the definitive biography.

Nabokov’s Pale Fire: The Magic of Artistic Discovery – Brian Boyd, Princeton University Press, 2001. Boyd argues that the book has two narrators, Shade and Charles Kinbote, but reveals that Kinbote had some strange and highly surprising help in writing his sections. In light of this interpretation, Pale Fire now looks distinctly less postmodern – and more interesting than ever.

Stalking Nabokov – Brian Boyd, Columbia University Press, 2013. This collection features essays incorporating material gleaned from Nabokov’s archive as well as new discoveries and formulations.

Nabokov’s ADA: The Place of Consciousness – Brian Boyd, Cybereditions Corporation, 2002. Provides not only the best commentary on Ada, but also a brilliant overview of Nabokov’s metaphysics, and has now been updated with a new preface, four additional chapters and two comprehensive new indexes.

Vladimir Nabokov – Lolita (Readers’ Guides to Essential Criticism) – Christine Clegg, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000. Examines the critical history of Lolita through a broad range of interpretations.

Nabokov’s Early Fiction : Patterns of Self and Other – Julian Connolly, Cambridge University Press, 1992. This book traces the evolution of Vladimir Nabokov’s prose fiction from the mid-1920s to the late 1930s. It focuses on a crucial subject: the relationship between self and other in its various forms (including character to character, character to author, author to reader).

Nabokov and his Fiction: New Perspectives – Julian W. Connolly, Cambridge University Press, 1999. This volume brings together the work of eleven of the world’s foremost Nabokov scholars, offering perspectives on the writer and his fiction. Their essays cover a broad range of topics and approaches, from close readings of major texts, including Speak, Memory and Pale Fire, to penetrating discussions of the significant relationship between Nabokov’s personal beliefs and experiences and his art.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov – Julian W. Connolly (ed), Cambridge University Press, 2005. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

Vladimir Nabokov (Writers & Their Work) – Neil Cornwell, Northcote House Publishers, 2008. A study that examines five of Nabokov’s major novels, plus his short stories and critical writings, situating his work against the ever-expanding mass of Nabokov scholarship.

Nabokov’s Eros and the Poetics of Desire – Maurice Couturier, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. A study which argues that Nabokov presented a whole spectrum of sexual behaviours ranging from standard to perverse, either sterile like bestiality, sexual lethargy or sadism, or poetically creative, like homosexuality, nympholeptcy and incest.

Style is Matter: The Moral Art of Vladimir Nabokov – Leyland De la Durantaye, Cornell University Press, 2010. A study focusing on Lolita but also addressing other major works (especially Speak, Memory and Pale Fire), asking whether the work of this writer whom many find cruel contains a moral message and, if so, why that message is so artfully concealed.

Nabokov His Life in Art a Critical Narrative – Andrew Field, Little, Brown & Co, 1967. A combination of biography and exploration of other works by one of the first serious Nabokov scholars – though they later fell into disagreement.

V. N.: Life and Art of Vladimir Nabokov – Andrew Field, TBS The Book Service, 1987. Andrew Field was one of the first major critics and biographers of Nabokov, although they later disagreed about his work and its interpretation.

Vladimir Nabokov: Bergsonian and Russian Formalist Influences in His Novels – Michael Glynn, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. This study seeks to counter the critical orthodoxy that conceives of Vladimir Nabokov as a Symbolist writer concerned with a transcendent reality.

Vladimir Nabokov an illustrated life – Jane Grayson, New York: Overlook, 2004. Short biography and introduction to his work, charmingly illustrated with period photos and sketches.

Freud and Nabokov – Geoffrey Green, University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

Nabokov’s Blues: The Scientific Odyssey of a Literary Genius – Kurt Johnson, McGraw-Hill, 2002. This book, which is part biography, explores the worldwide crisis in biodiversity and the place of butterflies in Nabokov’s fiction.

Vladimir Nabokov and the Art of Play – Thomas Karshan, Oxford University Press, 2011. This study traces the idea of art as play back to German aesthetics, and shows how Nabokov’s aesthetic outlook was formed by various Russian émigré writers who espoused those aesthetics. It then follows Nabokov’s exploration of play as subject and style through his whole oeuvre.

Reading Vladimir Nabokov: ‘Lolita’ – John Lennard, Humanities ebooks, 2012. Provides convenient overviews of Nabokov’s life and of the novel (including both Kubrick’s and Lyne’s film-adaptations), before considering Lolita as pornography, as lepidoptery, as film noir, and as parody.

Keys to the “Gift”: A Guide to Vladimir Nabokov’s Novel – Yuri Leving, Academic Studies Press, 2011. A new systematization of the main available data on Nabokov’s most complex Russian novel. From notes in Nabokov’s private correspondence to scholarly articles accumulated during the seventy years since the novel’s first appearance in print, this work draws from a broad spectrum of existing material in a succinct and coherent way, as well as providing innovative analyses.

Shades of Laura: Vladimir Nabokov’s Last Novel, the Original of Laura – Yuri Leving, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014. A collection of essays which investigate the event of publication and reconstitute the book’s critical reception, reproducing a selection of some of the most salient reviews.

Speak, Nabokov – Michael Maar, Verso, 2010. Using the themes that run through Nabokov’s fiction to illuminate the life that produced them, Maar constructs a compelling psychological and philosophical portrait.

Vladimir Nabokov: Poetry and the Lyric Voice – Paul D. Morris, University of Toronto Press, 2011. Offers a comprehensive reading of Nabokov’s Russian and English poetry, until now a neglected facet of his oeuvre. The study re-evaluates Nabokov s poetry and demonstrates that poetry was in fact central to his identity as an author and was the source of his distinctive authorial lyric voice.

Vladimir Nabokov – Norman Page, London: Routledge, 2013. The Critical Heritage is a collection of reviews and essays that trace the history and development of Nabokov’s critical reputation.

Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita: A Casebook – Ellen Pifer, Oxford University Press, 2002. This casebook gathers together an interview with Nabokov as well as nine critical essays. The essays follow a progression focusing first on textual and thematic features and then proceeding to broader issues and cultural implications, including the novel’s relations to other works of literature and art and the movies adapted from it.

The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov – Andrea Pitzer, Pegasus: Reprint edition, 2014. This book manages to be a number of things all at once – a biography, a primer on revolutionary Russian history, a critical survey of Nabokov’s novels, an act of literary detective work, and a cliffhanger narrative concerning a fateful dinner appointment between literary legends.

Vladimir Nabokov: A Pictorial Biography – Ellendea Proffer (ed), Ardis, 1991.

Vladimir Nabokov: A Tribute – Peter Quennell, Littlehampton Book Services, 1979.

Vladimir Nabokov: A Critical Study of the Novels – David Rampton, Cambridge University Press, 1984. This study assembles evidence from Nabokov’s own critical writings to show that the relationship of art to human life is central to Nabokov’s work. It pursues this argument through a close reading of novels from different stages of Nabokov’s career.

Nabokov in America: On the Road to Lolita – Robert Roper, Bloomsbury USA, 2015. Roper mined fresh sources to bring detail to Nabokov’s American journeys, and he traces their significant influence on his work – on two-lane highways and in late-’40s motels and cafés – to understand Nabokov’s seductive familiarity with the American mundane.

Nabokov at Cornell – Gavriel Shapiro, Cornell University Press, 2001. Contains twenty-five chapters by leading experts on Nabokov, ranging widely from Nabokov’s poetry to his prose, from his original fiction to translation and literary scholarship, from literature to visual art and from the humanities to natural science. The book concludes with a reminiscence of the family’s life in Ithaca by Nabokov’s son, Dmitri.

Nabokov’s Shakespeare – Samuel Shuman, Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. Explores the many and deep ways in which the works of Shakespeare penetrate the novels of Vladimir Nabokov, one of the finest English prose stylists of the twentieth century.

Chasing Lolita: How Popular Culture Corrupted Nabokov’s Little Girl All Over Again – Graham Vickers, Chicago Review Press, 2008. This study establishes who Lolita really was back in 1958, explores her predecessors of all stripes, and examines the multitude of movies, theatrical shows, literary spin-offs, artifacts, fashion, art, photography, and tabloid excesses that have distorted her identity and stolen her name.

Nabokov and the Art of Painting – Gerard de Vries and Donald Barton Johnson, Amsterdam University Press, 2014. Nabokov’s novels refer to over a hundred paintings, and show a brilliance of colours and light and dark are in a permanent dialogue with each other. Following the introduction describing the many associations Nabokov made between the literary and visual arts, several of his novels are discussed in detail.

Vladimir Nabokov (Critical Lives) – Barbara Wyllie, Reaktion Books, 2010. This book investigates the author’s poetry and prose in both Russian and English, and examines the relationship between Nabokov’s extraordinary erudition and the themes that recur across the span of his works

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on Vladimir Nabokov

More on literary studies

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories

Lolita

Lolita Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories Speak Memory

Speak Memory Despair

Despair Mary

Mary Laughter in the Dark

Laughter in the Dark The Gift

The Gift 1899. Vladimir Nabokov was born in St Petersburg on April 23 [the same birthday as Shakespeare]. His father was a prominent jurist, liberal politician, and a member of the Duma (Russia’s first parliament). His mother was the daughter of a wealthy aristocratic family.

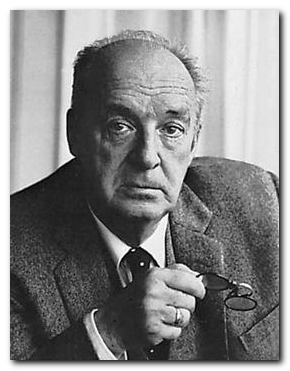

1899. Vladimir Nabokov was born in St Petersburg on April 23 [the same birthday as Shakespeare]. His father was a prominent jurist, liberal politician, and a member of the Duma (Russia’s first parliament). His mother was the daughter of a wealthy aristocratic family.  The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. It was written by the same author as the guidance notes on this page that you are reading right now.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. It was written by the same author as the guidance notes on this page that you are reading right now.