design , modernism, and Russian Suprematism

El Lissitzky (1890-1941) was one of the pioneers of the modernist movement in Russian art which flourished in the period 1915-1925. He was one of the most graphically radical of his era, and yet only a few years earlier he was painting rather conventional landscape paintings in the tradition of Russian realism. El Lissitzky’s earliest creative period was spent at Vitebsk working with Mark Chagall and Kasimir Malevich. With the latter he spearheaded to Suprematist movement. His geometric constructions developed from two to three dimensions and became a sort of theoretical architecture – shapes which float in space. He called the works ‘Proun’ – an invented word which means ‘Project for asserting the New’. El Lissitzky Design is an elegantly illustrated introduction to all this work.

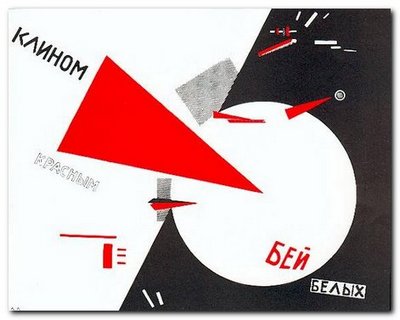

He is best known for his propaganda painting ‘Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge’ of 1919 – a work which very typically for its time was geometric in form, non-representational, and included typographical elements in the same style as his contemporaries Alexander Rodchenko and Malevich. At the same time he also started producing abstract constructions in two and three dimensions which were (like Rodchenko’s) geometrically based, but more mature and developed than any works of this kind that had emerged up to this date.

He is best known for his propaganda painting ‘Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge’ of 1919 – a work which very typically for its time was geometric in form, non-representational, and included typographical elements in the same style as his contemporaries Alexander Rodchenko and Malevich. At the same time he also started producing abstract constructions in two and three dimensions which were (like Rodchenko’s) geometrically based, but more mature and developed than any works of this kind that had emerged up to this date.

His finest work seems to have been produced in an amazing creative outburst between 1917 and 1925 – just at the point where unfettered Russian modernist art theory was taking off alongside the political revolution in its positive and expansive phase.

When El Lissitzky crossed the line between art and work after 1917, he became an international social activist promoting a political message. Like the Russian Constructivists that he admired, he sought to use his creative energy to help design a new social structure in which the new engineer-architect-artist could erase old boundaries.

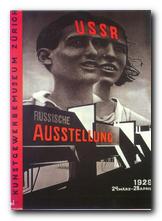

El Lissitzky was fortunate to be at his creative peak at a time when foreign travel was still possible in the USSR. He took exhibitions to Germany and mixed with other modernists such as Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Kurt Schwitters. He had connection with the De Stijl group in Holland, and he taught at the Bahaus.

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.

He lived until 1943, but there is very little that he produced after the mid 1920s that stands up to any degree of scrutiny today. What he produced before then was awe inspiring – and remains so to this day.

© Roy Johnson 2010

John Milner, El Lissitzky – Design, Suffolk: Antique Collectors Club, 2009, pp.96, ISBN: 185149619X

More on art

More on media

More on design

E.M.Forster is often seen as a bridge between the nineteenth and the twentieth century novel. He documents the Edwardian and Georgian periods in a witty and elegant prose, satirising the middle and upper classes he knew so well. He was a friend of Virginia Woolf, with whom he worked out some of the ground rules of literary modernism. These included the concept of what they called ‘tea-tabling’ – making the substance of serious fiction the ordinary events of everyday life. He was also an inner member of

E.M.Forster is often seen as a bridge between the nineteenth and the twentieth century novel. He documents the Edwardian and Georgian periods in a witty and elegant prose, satirising the middle and upper classes he knew so well. He was a friend of Virginia Woolf, with whom he worked out some of the ground rules of literary modernism. These included the concept of what they called ‘tea-tabling’ – making the substance of serious fiction the ordinary events of everyday life. He was also an inner member of  Where Angels Fear to Tread

Where Angels Fear to Tread Where Angels Fear to Tread – DVD This film version is not a Merchant-Ivory production, although it’s done very much in their style. But it is accurate and entirely sympathetic to the spirit of the novel, possibly even stronger in satirical edge, well acted, and superbly beautiful to watch. Much is made of the visual contrast between the beautiful Italian setting and the straight-laced English capital from which the prudery and imperialist spirit emerges. The lovely Helena Bonham-Carter establishes herself as the perfect English Rose in this her breakthrough production. Helen Mirren is wonderful as the spirited Lilia who defies English prudery and narrow-mindedness and marries for love – with results which manage to upset everyone.

Where Angels Fear to Tread – DVD This film version is not a Merchant-Ivory production, although it’s done very much in their style. But it is accurate and entirely sympathetic to the spirit of the novel, possibly even stronger in satirical edge, well acted, and superbly beautiful to watch. Much is made of the visual contrast between the beautiful Italian setting and the straight-laced English capital from which the prudery and imperialist spirit emerges. The lovely Helena Bonham-Carter establishes herself as the perfect English Rose in this her breakthrough production. Helen Mirren is wonderful as the spirited Lilia who defies English prudery and narrow-mindedness and marries for love – with results which manage to upset everyone. A Room with a View

A Room with a View A Room with a View – DVD This is a Merchant-Ivory production which takes one or two minor liberties with the original novel. But it’s still well acted, with the deliciously pouting Helena Bonham Carter as the heroine, Denholm Eliot as Mr Emerson, Daniel Day-Lewis as a wonderfully pompous Cecil Vyse, and Maggie Smith as the poisonous hanger-on Charlotte. The settings are delightfully poised between Florentine Italy and the home counties stockbroker belt. I’ve watched it several times, and it never ceases to be visually elegant and emotionally well observed. This film was nominated for eight Academy awards when it appeared, and put the Merchant-Ivory team on the cultural map.

A Room with a View – DVD This is a Merchant-Ivory production which takes one or two minor liberties with the original novel. But it’s still well acted, with the deliciously pouting Helena Bonham Carter as the heroine, Denholm Eliot as Mr Emerson, Daniel Day-Lewis as a wonderfully pompous Cecil Vyse, and Maggie Smith as the poisonous hanger-on Charlotte. The settings are delightfully poised between Florentine Italy and the home counties stockbroker belt. I’ve watched it several times, and it never ceases to be visually elegant and emotionally well observed. This film was nominated for eight Academy awards when it appeared, and put the Merchant-Ivory team on the cultural map. The Longest Journey

The Longest Journey Howards End

Howards End Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed.

Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed. A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece. A Passage to India – DVD This adaptation by David Lean is something of a mixed bag. It’s well organised, reasonably true to the original, and has some visually spectacular scenes. James Fox is convincing as the central character Fielding. But it has tonal inconsistencies, and to cast Alec Guinness as the Indian mystic Godbole is verging on the ridiculous. Nevertheless there is some good cameo acting, particularly Edith Evans as Mrs Moore. Watch out for the Indian signpost half way through that looks as if it’s made out of cardboard.

A Passage to India – DVD This adaptation by David Lean is something of a mixed bag. It’s well organised, reasonably true to the original, and has some visually spectacular scenes. James Fox is convincing as the central character Fielding. But it has tonal inconsistencies, and to cast Alec Guinness as the Indian mystic Godbole is verging on the ridiculous. Nevertheless there is some good cameo acting, particularly Edith Evans as Mrs Moore. Watch out for the Indian signpost half way through that looks as if it’s made out of cardboard. Maurice, (1967) is something from Forster’s bottom drawer. It was written in 1913-14, but not published until after his death. It’s an autobiographical novel of his gay university days which is explicit enough that couldn’t be published in his own lifetime. It’s light, amusing, and fairly inconsequential compared to the novels he wrote whilst pretending to be straight. This poses an interesting critical problem, when you would imagine he could have been more honest and therefore more successful.

Maurice, (1967) is something from Forster’s bottom drawer. It was written in 1913-14, but not published until after his death. It’s an autobiographical novel of his gay university days which is explicit enough that couldn’t be published in his own lifetime. It’s light, amusing, and fairly inconsequential compared to the novels he wrote whilst pretending to be straight. This poses an interesting critical problem, when you would imagine he could have been more honest and therefore more successful. Aspects of the Novel (1927) was originally a series of lectures on the nature of fiction. Forster discusses all the common elements of novels such as story, plot, and character. He shows how they are created, with all the insight of a skilled practitioner. Drawing on examples from classic European literature, he writes in a way which makes it all seem very straightforward and easily comprehensible. This book is highly recommended as an introduction to literary studies.

Aspects of the Novel (1927) was originally a series of lectures on the nature of fiction. Forster discusses all the common elements of novels such as story, plot, and character. He shows how they are created, with all the insight of a skilled practitioner. Drawing on examples from classic European literature, he writes in a way which makes it all seem very straightforward and easily comprehensible. This book is highly recommended as an introduction to literary studies. Collected Short Stories is like a glimpse into Forster’s workshop – where he tried out ideas for his longer fictions. This volume contains his best stories – The Story of a Panic, The Celestial Omnibus, The Road from Colonus, The Machine Stops, and The Eternal Moment. Most were written in the early part of Forster’s long career as a writer. Rich in irony and alive with sharp observations on the surprises in life, the tales often feature violent events, discomforting coincidences, and other odd happenings that throw the characters’ perceptions and beliefs off balance.

Collected Short Stories is like a glimpse into Forster’s workshop – where he tried out ideas for his longer fictions. This volume contains his best stories – The Story of a Panic, The Celestial Omnibus, The Road from Colonus, The Machine Stops, and The Eternal Moment. Most were written in the early part of Forster’s long career as a writer. Rich in irony and alive with sharp observations on the surprises in life, the tales often feature violent events, discomforting coincidences, and other odd happenings that throw the characters’ perceptions and beliefs off balance. E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.

E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended. The Cambridge Companion to Kafka offers a comprehensive account of his life and work, providing a rounded contemporary appraisal of Central Europe’s most distinctive Modernist. Contributions cover all the key texts, and discuss Kafka’s writing in a variety of critical contexts such as feminism, deconstruction, psycho-analysis, Marxism, and Jewish studies. Other chapters discuss his impact on popular culture and film. The essays are well supported by supplementary material including a chronology of the period and detailed guides to further reading, and will be of interest to students of Comparative Literature.

The Cambridge Companion to Kafka offers a comprehensive account of his life and work, providing a rounded contemporary appraisal of Central Europe’s most distinctive Modernist. Contributions cover all the key texts, and discuss Kafka’s writing in a variety of critical contexts such as feminism, deconstruction, psycho-analysis, Marxism, and Jewish studies. Other chapters discuss his impact on popular culture and film. The essays are well supported by supplementary material including a chronology of the period and detailed guides to further reading, and will be of interest to students of Comparative Literature.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis The Trial

The Trial The Castle

The Castle Amerika

Amerika The Complete Short Stories

The Complete Short Stories The Diaries

The Diaries Letters to Felice

Letters to Felice The Complete Novels

The Complete Novels Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. An excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. An excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully. Kafka: A Very Short Introduction introduces Kafka’s life and cultural background, then traces a number of themes in his best-known works. It’s in an interesting and attractive format – a small, pocket-sized book, stylishly designed, with illustrations, endnotes, suggestions for further reading, and an index. If you’ve not studied Kafka before, this will give you pointers on what to look for. It covers Kafka’s biography, then interpretations of his work – including one quite original approach concerning the relationship between his writing and his body.

Kafka: A Very Short Introduction introduces Kafka’s life and cultural background, then traces a number of themes in his best-known works. It’s in an interesting and attractive format – a small, pocket-sized book, stylishly designed, with illustrations, endnotes, suggestions for further reading, and an index. If you’ve not studied Kafka before, this will give you pointers on what to look for. It covers Kafka’s biography, then interpretations of his work – including one quite original approach concerning the relationship between his writing and his body.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.