biography, guidance notes, and critical essays

This complete critical guide to Jane Austen comes from a new series by Routledge which offers comprehensive but single-volume introductions to major English writers. They are aimed at students of literature, but are accessible to general readers who might like to deepen their understanding. The approach taken is quite straightforward. Part One is a potted biography of Austen, placing her life and work in a socio-historical context. This takes into account the role of women in the early nineteenth century; the position of a female author in the world of book publishing at the time; the social conventions surrounding women and marriage; and the sheer political fact that she was living at the time of the French revolution and war between Britain and France.

Part Two provides a synoptic view of Austen’s six great novels – from Northanger Abbey to Persuasion. The works are described in outline, and then their main themes illuminated. This is followed by pointers towards the main critical writings on these texts and issues.

Part Two provides a synoptic view of Austen’s six great novels – from Northanger Abbey to Persuasion. The works are described in outline, and then their main themes illuminated. This is followed by pointers towards the main critical writings on these texts and issues.

Part Three deals with criticism of Austen’s work. This is presented in chronological order – from contemporaries such as Walter Scott to critics of the present day, with the focus on feminist and gender criticism, Marxist, and psychoanalytic criticism. Some of the readings Irvine outlines will be quite provocative and surprising to many readers – particularly those dealing with such issues as slavery in Mansfield Park and both sexual and homosexual readings of Sense and Sensibility.

The book ends with a commendably thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Austen journals. There is also a separate chapter which deals with Austen on screen. This discusses the controversial issue of Austen’s work as it has been appropriated to project modern notions of English nationalism and the ‘heritage industry’.

This will be an excellent starting point for students who are new to Austen’s work – and a refresher course for those who would like to keep up to date with criticism. And it certainly is up to date – with references to publications only just over a year old at the time of publication.

© Roy Johnson 2005

Robert P. Irvine, The Complete Critical Guide to Jane Austen, Abingdon: Routledge, 2005, pp.190, ISBN 0415314356

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

A disaster befalls Gabriel’s farm and he loses his sheep; he is forced to give up farming. He goes looking for work, and in his travels finds himself in Weatherbury. After rescuing a local farm from fire he asks the mistress if she needs a shepherd. It is Bathsheba, and she hires him.

A disaster befalls Gabriel’s farm and he loses his sheep; he is forced to give up farming. He goes looking for work, and in his travels finds himself in Weatherbury. After rescuing a local farm from fire he asks the mistress if she needs a shepherd. It is Bathsheba, and she hires him.

The Return of the Native

The Return of the Native The Mayor of Casterbridge

The Mayor of Casterbridge

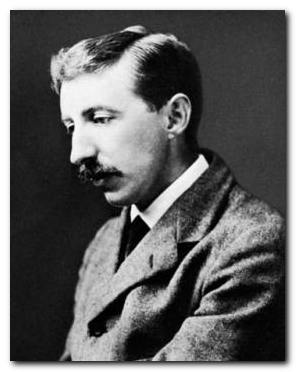

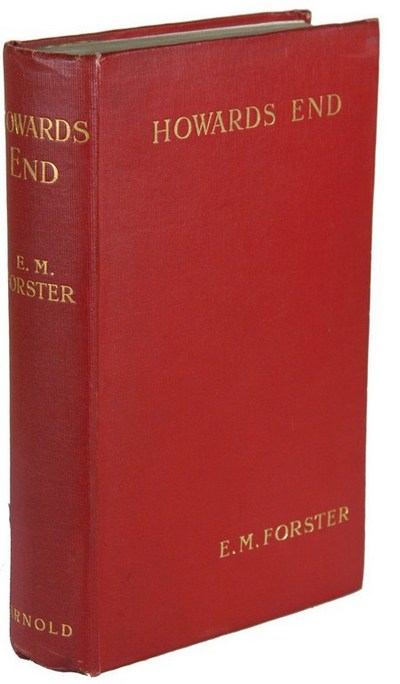

The Longest Journey

The Longest Journey A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

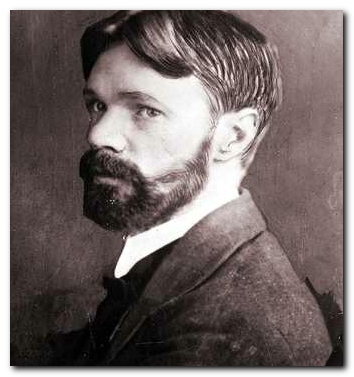

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first.

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first. Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Sons and Lovers

Sons and Lovers Women in Love

Women in Love

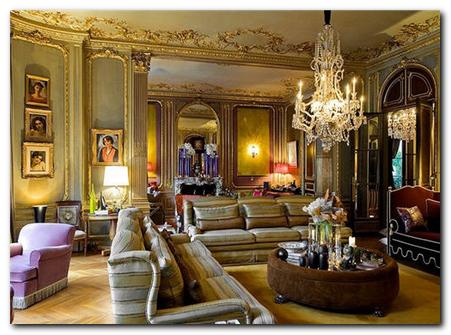

Following Sasha’s return to Russia, the desolate, lonely Orlando returns to writing The Oak Tree, a poem started and abandoned in his youth. This period of contemplating love and life leads him to appreciate the value of his ancestral stately home, which he proceeds to furnish lavishly and then plays host to the populace. Ennui sets in and a persistent suitor’s harassment leads to Orlando’s appointment by King Charles II as British ambassador to Constantinople. Orlando performs his duties well, until a night of civil unrest and murderous riots. He falls asleep for a lengthy period, resisting all efforts to rouse him.

Following Sasha’s return to Russia, the desolate, lonely Orlando returns to writing The Oak Tree, a poem started and abandoned in his youth. This period of contemplating love and life leads him to appreciate the value of his ancestral stately home, which he proceeds to furnish lavishly and then plays host to the populace. Ennui sets in and a persistent suitor’s harassment leads to Orlando’s appointment by King Charles II as British ambassador to Constantinople. Orlando performs his duties well, until a night of civil unrest and murderous riots. He falls asleep for a lengthy period, resisting all efforts to rouse him.

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse The Complete Shorter Fiction

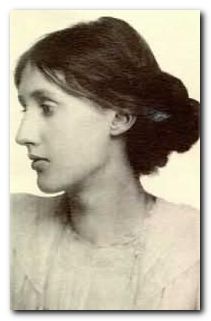

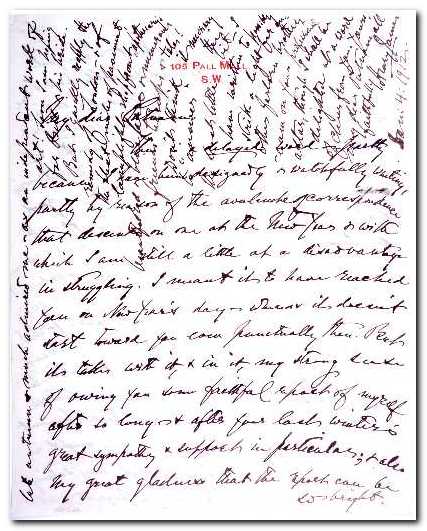

The Complete Shorter Fiction The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad Nostromo

Nostromo The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent