tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

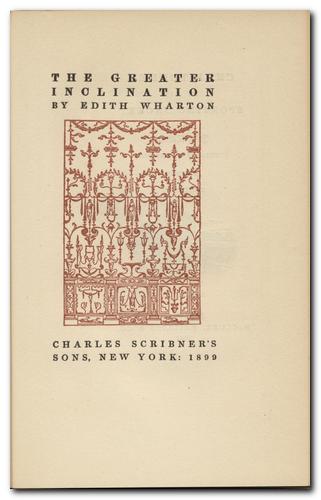

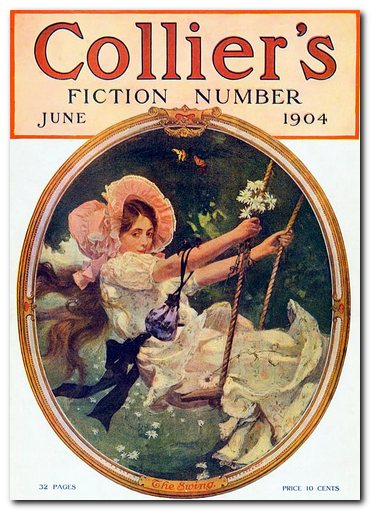

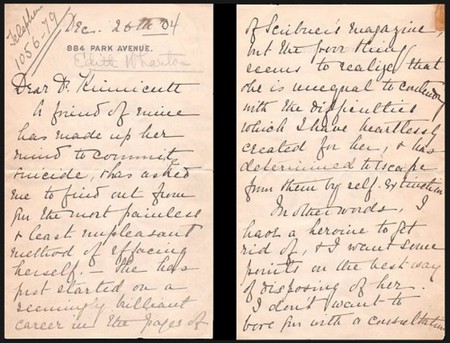

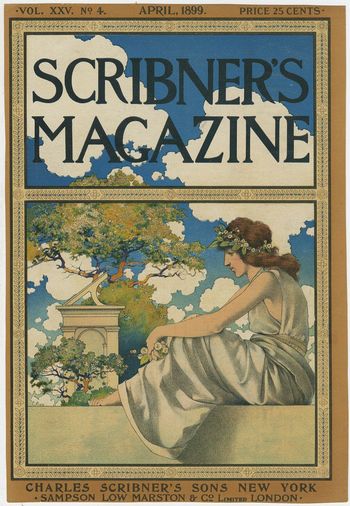

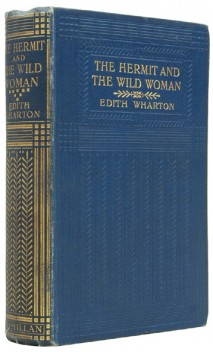

The Muse’s Tragedy first appeared in the Scribner’s Magazine number 25 for January 1899. The story was included in the first collection of Edith Wharton’s short stories, The Greater Inclination published in New York by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1899.

first edition – cover design by Berkeley Updike

The Muse’s Tragedy – critical commentary

The principal feature of interest in this early story is the manner in which the narrative is composed. It has a remarkably poised structure, and although its is essentially a ‘reversal of expectation’ tale, Wharton brings quite an original approach to the arrangement of events in the narrative – particularly in omitting what would normally be considered a crucial part of the narrative.

In the first two parts of the story events are related from Lewis Danyers’ point of view. We learn of his admiration for the work of Victor Rendle, and his feeling of good fortune on meeting the still-attractive Mary Anerton, the muse of Rendle’s most famous poems. These two elements appear to be successfully fused when at the end of their stay at the Hotel Villa d’Este she persuades him to write a study on Rendle and agrees to help him work on it.

They go to Venice and spend a month together, during which time we learn (later) that Danyers falls in love with Mary Anerton and asks her to marry him. But none of this information is relayed directly. In fact the whole of their stay is omitted from the narrative. Instead, Wharton jumps ahead to the day following its conclusion, and part three of the story is a letter written by Mary explaining to Danyers why she cannot marry him.

The letter explains her past as the muse of Vincent Rendle, her devoted love for him, and her disappointment at not being loved in return. All the earlier information Danyers has gathered seemed to point towards a secret affair between the poet and the woman who inspired his best work. She was after all married to Mr Anerton, who tolerated Rendle’s close relationship with his wife, and even invited him on holiday with them.

But the bitter irony for Mary is that though she worshipped Rendle for fifteen years, her love was not reciprocated, and she is left wondering what it might be like to be loved for herself alone. She has found out during her four weeks with Danyers in Venice, but she feels that although she loves Danyers, she cannot allow him to marry a ‘disappointed woman’.

The letter explains some her earlier behaviour, including her cool reception of Danyers’ essay on Rendle. By the time of receiving the essay, Mary Anerton has become galled by the irony of being viewed as the muse of Rendle’s work – because he has taken the inspiration from her, but offered nothing in return. It also explains why she has been happy to spend a month together with Danyers without once discussing the proposed study of Rendle and his work. By this point she is heartily sick of the work she has inspired. That is her ‘tragedy’.

The Muse’s Tragedy – study resources

![]() The Works of Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Works of Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

![]() The Works of Edith Wharton – Amazon US

The Works of Edith Wharton – Amazon US

![]() Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

![]() Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon US

Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon US

![]() The Descent of Man and Other Stories – Project Gutenberg

The Descent of Man and Other Stories – Project Gutenberg

![]() A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Muse’s Tragedy – plot summary

Part I. Lewis Danyers is a young American who has written a prize-winning essay on the poetry of Vincent Rendle, much of whose work has been inspired by his muse, Mrs Mary Anerton. When Danyers’ friend Mrs Memorall reveals that Mary Anerton was her childhood friend, it fires his imagination and his desire to know more about the inspiration for so much great poetry. The public has been kept at bay by Rendle, and even Mary Anerton’s husband has been protective of the association with such a revered artist.

Since the death of both Vincent Rendle and her husband, Mary Anerton has become lonely and introspective. Mrs Memorall thinks she should remarry, but she did not marry Rendle when she had the chance. Danyers republishes his appreciation of Rendle, and Mrs Memorall sends a copy to Mary Anerton, where it receives a polite but cool reception. However, when he meets Mary at the Hotel Villa d’Este, she compliments him warmly on his work.

Part II. During their stay at the hotel, Danyers gets to know Mary Anerton very well, and he realises that she knows every last detail of Rendle’s work, and also that she has an original intelligence of her own which is reflected in the poetry. May encourages Danyers to write a book on Rendle, which he agrees to if she will help him work on it.

Part III. They spend a month together in Venice, during which time it becomes obvious that they have fallen in love and he has made her a proposal of marriage. Mary writes Danyers a letter the day after the end of their sojourn explaining why she cannot accept his offer and giving a full explanation of her relationship with Vincent Rendle.

She was in love with Rendle and he was inspired by her – but he only regarded her as a friend. She gave up fifteen years of her life to him and has emerged empty-handed at the end of it. People assumed she was his lover, but this was not true. She has even edited his letters to her, making it appear as if they omitted personal details and references – when there was nothing there in the first place.

He even continued sharing his ideas on poetry with her whilst he was chasing after a young girl in Switzerland. When her husband died, her hopes rose – then fell back again when Rendle merely resumed their old friendship. When Rendle himself dies, she becomes famous as his love object. She goes through black periods and asks herself why Rendle didn’t love her, and wonders if she simply isn’t attractive to men.

This has led up to her month in Venice with Danyers. She was attracted to him and wanted to be loved for herself – not because she was the muse of somebody’s poems. She realises that Danyers loved her for herself, and they spent a month in Venice without even mentioning the proposed book which was the ostensible reason for the vacation. Now, even though she has discovered what it means to be loved, she feels she must renounce him to save Danyers from marrying ‘a disappointed woman’.

The Muse’s Tragedy – Principal characters

| Lewis Danyers | a young scholar |

| Mrs Mary Anerton | ‘Sylvia’, the muse of Vincent Rendle |

| Mr Anerton | her indulgent husband |

| Vincent Rendle | a reclusive poet |

| Mrs Memorall | a friend of Danyers |

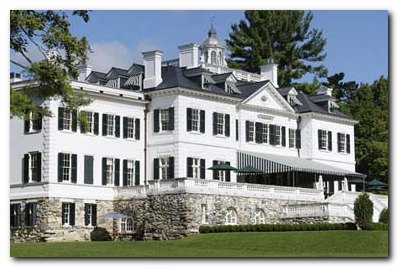

Edith Wharton’s 42-room house – The Mount

Further reading

Louis Auchincloss, Edith Wharton: A Woman of her Time, New York: Viking, 1971,

Elizabeth Ammons, Edith Wharton’s Argument with America, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1982, pp.222. ISBN: 0820305138

Janet Beer, Edith Wharton (Writers & Their Work), New York: Northcote House, 2001, pp.99, ISBN: 0746308981

Millicent Bell (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Edith Wharton, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp.232, ISBN: 0521485134

Alfred Bendixen and Annette Zilversmit (eds), Edith Wharton: New Critical Essays, New York: Garland, 1992, pp.329, ISBN: 0824078489

Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN: 0810927950

Gloria C. Erlich, The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton, California: University of California Press, 1992, pp.223, ISBN: 0520075838

Susan Goodman, Edith Wharton’s Women: Friends and Rivals, UPNE, 1990, pp.220, ISBN: 0874515246

Irving Howe, (ed), Edith Wharton: A collection of Critical Essays, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1986,

Jennie A. Kassanoff, Edith Wharton and the Politics of Race, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp.240, ISBN: 0521830893

Hermione Lee, Edith Wharton, London: Vintage, new edition 2008, pp.864, ISBN: 0099763516

R.W.B. Lewis, Edith Wharton: A Biography, New York: Harper and Rowe, 1975, pp.592, ISBN: 0880640200

James W. Tuttleton (ed), Edith Wharton: The Contemporary Reviews, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.586, ISBN: 0521383196

Candace Waid, Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991,

Sarah Bird Wright, Edith Wharton A to Z: The Essential Reference to Her Life and Work, Fact on File, 1998, pp.352, ISBN: 0816034818

Cynthia Griffin Wolff, A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton, New York: Perseus Books, second edition 1994, pp.512, ISBN: 0201409186

Other works by Edith Wharton

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Edith Wharton – web links

Edith Wharton at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, tutorials on the shorter fiction, bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

The Short Stories of Edith Wharton

This is an old-fashioned but excellently detailed site listing the publication details of all Edith Wharton’s eighty-six short stories – with links to digital versions available free on line.

Edith Wharton at Gutenberg

Free eTexts of the major novels and collections of stories in a variety of digital formats – also includes travel writing and interior design.

Edith Wharton at Wikipedia

Full details of novels, stories, and travel writing, adaptations for television and the cinema, plus web links to related sites.

The Edith Wharton Society

Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University.

The Mount: Edith Wharton’s Home

Aggressively commercial site devoted to exploiting The Mount – the house and estate designed by Edith Wharton. Plan your wedding reception here.

Edith Wharton at Fantastic Fiction

A compilation which purports to be a complete bibliography, arranged as novels, collections, non-fiction, anthologies, short stories, letters, and commentaries – but is largely links to book-selling sites, which however contain some hidden gems.

Edith Wharton’s manuscripts

Archive of Wharton holdings at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© Roy Johnson 2014

Edith Wharton – short stories

More on Edith Wharton

More on short stories

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.