tutorial, study guide, commentary, further reading, web links

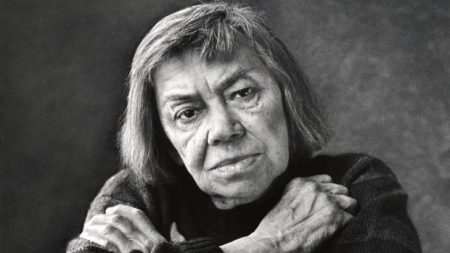

Ripley Under Ground (1977) is the second of Patricia Highsmith’s novels featuring her anti-hero Tom Ripley. He is a young and ambitious American from a poor background who has a taste for art, luxuries, and fine living. He is enterprising and imaginative, likes to takes chances, and is not averse to murdering anybody who gets in his way.

There is a series of five Ripley novels, which have become known collectively as The Ripliad. They are self-contained and can be enjoyed separately – but an acquaintance with their chronological development adds depth to their meaning – particularly the ironic contrasts between Ripley’s refined social tastes and his shocking exploits.

Ripley Under Ground – commentary

Background

Since the events of The Talented Mr Ripley (1970) Tom Ripley has ‘retired’ to live in France, and has married Heloise Plisson. He has three sources of income – all gained illegally. The first is Dickie Greenleaf’s inheritance, which he has appropriated by forging Dickie’s will. The second is a business centred on the creation of fake paintings by an artist Derwatt, who is now dead. The third is a courier service for illegal goods sent to him by an associate Reeves Minot from Hamburg.

Ripley has escaped detection for the murders of Dickie Greenleaf and Freddie Miles, and yet a certain opprobrium attaches itself to his name. He is also supported by regular maintenance payments his wife receives from her father, a millionaire pharmaceutical manufacturer who is sceptical about her marriage to Ripley.

Murder and morality

What makes this and the other Ripley novels interesting is the tension between Ripley as a character and what he does. We know that he is a confidence trickster who is living off other people’s money; that he is prepared to adopt another person’s identity; forge letters; lie to the police; and generally evade detection so that he can go on living a comfortable life.

That is Part One of the down side to his character. But he also has positive characteristics. He likes good food and wine; he takes an interest in art; he is considerate to friends and neighbours; and his taste in fine clothes and furniture is based on a genuine appreciation of their quality – not on any snobbish and nouveau-riche accumulation of status objects.

Part Two of his character however, is problematic. Not only does he break the law in matters of finance and irregular business practices – he actually murders people. This is more difficult to defend.

The only possible defence is aesthetic – an acceptance that Patricia Highsmith is offering an entertaining character study in radical existentialism. She makes her protagonist an intelligent and cultivated character who rationalises his crimes by only murdering ‘unsympathetic’ characters. It also has to be said that some of the murderous situations in which Ripley finds himself can be quite funny – in a macabre, black humour sort of way.

Ripley the Protean

We know from the first of the Ripley novels that he is very skillful at imitating the sound of other people’s voices. In Ripley Under Ground he goes one further and convincingly impersonates someone (Derwatt) who has died a few years previously. He transforms himself twice to pull off this trick – though it has to be said that none of the people before whom he puts on this performance would know what Derwatt originally looked like.

Ripley also identifies very intently with certain other people – usually the underdog. He understands why Bernard Tufts wishes to abandon his role as a Derwatt imitator and return to his own career as a painter. This will bring one element of Ripley’s profitable company Derwatt Ltd to a close, but he sympathises with Bernard’s plight – possibly as a fellow amateur painter himself.

Indeed, he carries this sympathy to extraordinary lengths, because Bernard blames Ripley for bringing him to a personal crisis of identity and twice tries to kill him. He even buries him alive (hence the book’s title) yet Ripley seemingly bears no grudge against him.

Ripley also has multiple identities. He lives an apparently blameless life in a quiet French village; yet he has a corrupt business network that stretches to Hamburg and London. He is quite happy to travel on a forged passport. He is a gentleman to his housekeeper, a devoted husband to his wife, and a secretive mystery to everyone else.

Ripley also flits quite easily between two languages – English and French. (We learn later that he also speaks Italian.) In fact he is something of an amateur linguaphile – and he often wonders what the word for an object is in a number of different languages.

The conclusion

Without doubting for a moment Patricia Highsmith’s skill at plotting, her attention to detail, and her knowledge of the technicalities of crime – the conclusion to Ripley Under Ground does seem to raise a few problems.

The novel ends with Bernard’s suicide and Tom’s cremation of the body. We learn in the next novel Ripley Under Ground that Tom returned to the scene of this gruesome bonfire with Inspector Webster, to be questioned closely about the incident – which the police mistakenly think is the death of Derwatt.

Ripley is able to talk his way out of things as usual. But surely there is something more fundamentally wrong here? It is difficult to believe that failing to report a death (Bernard’s suicidal fall over the cliff) would not be regarded as a crime in most European countries. Even more seriously – the private cremation of an unreported dead body would be a very serious crime indeed.

Ripley does his best to remove evidence for identifying the corpse by shattering the skull and detaching the lower jawbone. At that time (prior to DNA technology) recognition of unidentified bodies was often based on dental records, of which there are none for Derwatt. This is a typical and delicious double plot irony on Highsmith’s part, since it was not Derwatt’s corpse that was cremated, but Bernard’s.

But these macabre details apart, surely Inspector Webster or the Salzburg police would have arrested Ripley for the unofficial cremation of an unidentified corpse in a pubic place?

Highsmith was operating within a literary genre (the crime thriller) that often has less exacting standards of logic and credibility in its narratives than the traditional realist novel of the nineteenth and twentieth century. Yet such is the quality of her writing and the seriousness of her themes that she seems to invite comparisons with this tradition.

The giants of the realist novel didn’t always avoid technical errors in their work. From Wuthering Heights (1847) to Nostromo (1904) there are chronological infelicities and logical flaws in many classic narratives – but they tend to be of a minor nature and not crucial to the outcome of events.

Highsmith plays slightly fast and lose in this respect with the credibility of her narratives. For instance, Ripley’s often-absent wife Heloise, who comes from a very ‘respectable’ family, actually tolerates the fact that her husband is a murderer. She knows Ripley has killed Murchison in their wine cellar – but she remains unconcerned and as peripheral to the narrative as Highsmith requires for a tidy conclusion. This part of the story is simply not credible in realistic terms.

Ripley’s Game – study resources

![]() Ripley Under Ground – Penguin – Amazon UK

Ripley Under Ground – Penguin – Amazon UK

![]() Ripley Under Ground – Penguin – Amazon US

Ripley Under Ground – Penguin – Amazon US

![]() Ripley Under Ground – Kindle – Amazon UK

Ripley Under Ground – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Ripley Under Ground – Kindle – Amazon US

Ripley Under Ground – Kindle – Amazon US

![]() Ripley Complete – Box Set – Amazon UK

Ripley Complete – Box Set – Amazon UK

The complete Ripliad

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

Ripley Under Ground (1970)

Ripley Under Ground (1974)

The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980)

Ripley Under Water (1991)

Ripley Under Ground – plot summary

Tom Ripley is living in a large house called Belle Ombre with gardens outside Paris. He is married to Heloise and running a fraudulent art business in London dealing in faked paintings by Bernard Tufts in the style of an artist Derwatt who has died some years ago in Greece. Ripley also acts as an intermediary in shady business transactions with his associate Reeves Minot in Hamburg.

An exhibition of Dewatt’s work is due to open, and one customer is going to challenge the authenticity of a work he has bought. Tom proposes to act the part of Derwatt at the opening of the exhibition.

He dresses in disguise and answers questions from the press. Then the American collector Murchison claims that paintings are being faked. He wants an expert opinion and thinks the gallery’s records of sale should be inspected. Tom invites Murchison to Paris to compare Derwatt paintings.

They have dinner and discuss the pros and cons of forgery. Next day prior to his departure for London, Tom appeals to Murchison’s sporting sense on the issue of forgeries. When Murchison flatly refuses, Tom kills him in his wine cellar.

Tom drives to Orly airport, dumps Murchison’s suitcase and painting, then collects a courier from Reeves. He takes the courier back for dinner and extracts a microfilm hidden in a tube of toothpaste.

Next day he receives a letter announcing the arrival from California of Chris Greenleaf (Dickie’s younger cousin). The he starts burying Murchison’s body in some nearby woods. Next day Chris arrives and the police start asking questions about Murchison, all of which Ripley answers quite convincingly.

Bernard Tufts suddenly arrives and acts strangely. He wants to put an end to the Derwatt forgeries, and wishes to confess his part in the swindle – so as to reclaim his own identity and self-esteem as a serious painter.

Bernard helps Tom to dig up the body, which they dump in a river some distance away. A London police inspector Webster arrives. Tom appears to answer all his questions quite truthfully.

Bernard is depressed and suddenly disappears. Heloise arrives from Greece and discovers a body hanging in the cellar. It turns out to be a dummy, made by Bernard to represent the death of his old self.

Bernard turns up again and wants to stay. That night he tries to kill Tom, who he blames for all his problems. Next day he attacks Tom again and buries him in Murchison’s old grave. Tom manages to escape, but thinks it will be safer to act as if dead.

He orders new fake passports from Reeves in Hamburg, flies to the Greek islands in search of Bernard, but finds nothing. Back in London he makes a final appearance as Derwatt. He confronts Inspector Webster and Mrs Murchison, but answers their queries with half truths. But as Heloise becomes more suspicious he confesses to her that he has killed Murchison.

Tom flies to Salzburg where he spots Bernard in the Mozart museum. When they meet again in a restaurant, Bernard is clearly shocked to find Tom alive. Next day Tom pursues Bernard through the outskirts of town

until Bernard falls over a cliff and dies from the fall. Tom returns to the scene and very laboriously cremates the body.

Tom goes back home where Webster arrives next day. He questions Tom closely about the two (apparent) deaths in Salzburg. But Tom has all the necessary answers, and lives on to feature in two further volumes of The Ripliad.

Ripley Under Ground – characters

| Tom Ripley | a young American confidence man |

| Heloise Plisson | his beautiful and wealthy wife |

| Bernard Tufts | an amateur painter and forger |

| Jeff Constant | a photographer and gallery owner |

| Edmund Banbury | journalist and gallery owner |

| Thomas Murchison | an American industrialist and art collector |

| Chris Greenleaf | younger cousin of Dickie Greenleaf |

| Cynthia Gradnor | Bernard’s disillusioned girlfriend |

© Roy Johnson 2017

More Patricia Highsmith

Twentieth century literature

More on short stories

C=criticism

C=criticism The Complete Critical Guide to Samuel Beckett

The Complete Critical Guide to Samuel Beckett Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life

Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life The Cambridge Companion to Beckett

The Cambridge Companion to Beckett Murphy is Samuel Beckett’s first novel, published in 1938. It was written in English, unlike many of his later works which were written in French then translated into English. It is the story of a work-shy man, wandering adrift in London, who believes that human desire can never be satisfied. He seeks to withdraw from life into a state of what he sees as catatonic bliss. Murphy’s fiancée Celia tries to humanise him by finding him a job working as a nurse in a mental institution, but he sees the insanity of the patients an attractive alternative to his conscious existence from which he cannot escape.

Murphy is Samuel Beckett’s first novel, published in 1938. It was written in English, unlike many of his later works which were written in French then translated into English. It is the story of a work-shy man, wandering adrift in London, who believes that human desire can never be satisfied. He seeks to withdraw from life into a state of what he sees as catatonic bliss. Murphy’s fiancée Celia tries to humanise him by finding him a job working as a nurse in a mental institution, but he sees the insanity of the patients an attractive alternative to his conscious existence from which he cannot escape. Watt Beckett’s second novel was written during World War Two (1942-1944), while he was hiding from the Gestapo in Provence in southern France. It was first published in English in 1953 and tells a semi-incoherent story of Watt’s journey to become the manservant of a Mr Knott, and his struggle to understand the house they live in. It’s written with some of Beckett’s characteristically deadpan humour and quasi-philosophic jokes. He also uses deliberately unidiomatic language and pokes fun at contemporary figures and institutions. Watt has previously appeared in editions that are littered with major and minor errors. The new Faber edition offers for the first time a corrected text based on a scholarly appraisal of the manuscripts and their textual history.

Watt Beckett’s second novel was written during World War Two (1942-1944), while he was hiding from the Gestapo in Provence in southern France. It was first published in English in 1953 and tells a semi-incoherent story of Watt’s journey to become the manservant of a Mr Knott, and his struggle to understand the house they live in. It’s written with some of Beckett’s characteristically deadpan humour and quasi-philosophic jokes. He also uses deliberately unidiomatic language and pokes fun at contemporary figures and institutions. Watt has previously appeared in editions that are littered with major and minor errors. The new Faber edition offers for the first time a corrected text based on a scholarly appraisal of the manuscripts and their textual history. The Trilogy This is the famous trilogy that is generally regarded as the pinnacle of Beckett’s work as an experimental novelist. He was pushing the developments of modernism, existentialism, and absurdism as far as they would go. The three novels follow the bleak logic of Beckett’s move away from movement and life, towards stasis and death. Molloy (1951) is set in an indeterminate place and comprises the inner monologues of Molloy and a private detective called Moran. Both live in a state of semi-absurdity and seem almost to merge into the same person as they lose bodily mobility and end up using crutches. Malone Dies (1951) is the story of an old man who is confined to bed in a hospital or an asylum (he is not sure which). All notions of conventional plot or logical sequences of events are abandoned. The narrative is merely Malone’s obsession with the trivia of his existence, stripped of all physical effects except an exercise book and a pencil that is getting shorter and shorter. The Unnameable (1953) takes these experiments in prose fiction one stage further. It concerns a person with no name who lives under an old tarpaulin sheet. He is not even sure if he is dead or alive – and neither are we.

The Trilogy This is the famous trilogy that is generally regarded as the pinnacle of Beckett’s work as an experimental novelist. He was pushing the developments of modernism, existentialism, and absurdism as far as they would go. The three novels follow the bleak logic of Beckett’s move away from movement and life, towards stasis and death. Molloy (1951) is set in an indeterminate place and comprises the inner monologues of Molloy and a private detective called Moran. Both live in a state of semi-absurdity and seem almost to merge into the same person as they lose bodily mobility and end up using crutches. Malone Dies (1951) is the story of an old man who is confined to bed in a hospital or an asylum (he is not sure which). All notions of conventional plot or logical sequences of events are abandoned. The narrative is merely Malone’s obsession with the trivia of his existence, stripped of all physical effects except an exercise book and a pencil that is getting shorter and shorter. The Unnameable (1953) takes these experiments in prose fiction one stage further. It concerns a person with no name who lives under an old tarpaulin sheet. He is not even sure if he is dead or alive – and neither are we. The Expelled This collection of four stories or nouvelles represents work which dates from 1945, though they were all published much later, in French and then in English. Full contents: The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, and First Love. All the stories make use of a first-person narrator, and exploit its potential for expressing the frailties of human memory, the inability to distinguish the past from the present, and even a profound doubt concerning the purpose of life itself. The stories document the human condition of an unstoppable progress towards death.

The Expelled This collection of four stories or nouvelles represents work which dates from 1945, though they were all published much later, in French and then in English. Full contents: The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, and First Love. All the stories make use of a first-person narrator, and exploit its potential for expressing the frailties of human memory, the inability to distinguish the past from the present, and even a profound doubt concerning the purpose of life itself. The stories document the human condition of an unstoppable progress towards death. How It Is Published in French in 1961, and in English in 1964, this presents a novel in three parts, written in short paragraphs, which tell of a narrator lying in the dark, in the mud, repeating his life as he hears it uttered – or remembered – by another voice. Told from within, from the dark, the story is tirelessly and intimately explicit about the feelings that pervade his world, but fragmentary and vague about all else therein or beyond. The novel counts for many readers as Beckett’s greatest accomplishment in the prose narrative form. It is also his most challenging work, both stylistically and for the radical pessimism of its vision, which continues the themes of reduced circumstance, of another life before the present, and the self-appraising search for an essential self.

How It Is Published in French in 1961, and in English in 1964, this presents a novel in three parts, written in short paragraphs, which tell of a narrator lying in the dark, in the mud, repeating his life as he hears it uttered – or remembered – by another voice. Told from within, from the dark, the story is tirelessly and intimately explicit about the feelings that pervade his world, but fragmentary and vague about all else therein or beyond. The novel counts for many readers as Beckett’s greatest accomplishment in the prose narrative form. It is also his most challenging work, both stylistically and for the radical pessimism of its vision, which continues the themes of reduced circumstance, of another life before the present, and the self-appraising search for an essential self. Company These four last prose fictions span the final decade of Beckett’s life. In the title sytory a solitary listener lying in darkness calls up images from a past life. Ill Seen Ill Said is a meditation on an old woman living out her final days in an isolated cottage, watched over by a dozen mysterious sentinels. In Worstward Ho, a breathless speaker unravels the sense of life, acting out the repeated injunction to ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ Stirrings Still was published in the Guardian a few months before Beckett’s death in 1989. It is his last prose work and testament. The Faber edition also includes several short prose texts (Heard in the Dark I & II, One Evening, The Way, Ceiling) which represent works in progress or fragments composed around the same time as his final writing.

Company These four last prose fictions span the final decade of Beckett’s life. In the title sytory a solitary listener lying in darkness calls up images from a past life. Ill Seen Ill Said is a meditation on an old woman living out her final days in an isolated cottage, watched over by a dozen mysterious sentinels. In Worstward Ho, a breathless speaker unravels the sense of life, acting out the repeated injunction to ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ Stirrings Still was published in the Guardian a few months before Beckett’s death in 1989. It is his last prose work and testament. The Faber edition also includes several short prose texts (Heard in the Dark I & II, One Evening, The Way, Ceiling) which represent works in progress or fragments composed around the same time as his final writing. Works for Radio

Works for Radio Complete Dramatic Works This one-volume compendium contains all of Beckett’s dramatic texts written between 1955 and 1984. It includes both the major dramatic works and the shorter and more compressed texts he created for the stage and for radio. Full contents: Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Happy Days, All That Fall, Acts Without Words, Krapp’s Last Tape, Roughs for the Theatre, Embers, Roughs for the Radio, Words and Music, Cascando, Play, Film, The Old Tune, Come and Go, Eh Joe, Breath, Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio,…but the clouds…, A Piece of Monologue, Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Quad, Catastrophe, Nacht und Traume, What Where.

Complete Dramatic Works This one-volume compendium contains all of Beckett’s dramatic texts written between 1955 and 1984. It includes both the major dramatic works and the shorter and more compressed texts he created for the stage and for radio. Full contents: Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Happy Days, All That Fall, Acts Without Words, Krapp’s Last Tape, Roughs for the Theatre, Embers, Roughs for the Radio, Words and Music, Cascando, Play, Film, The Old Tune, Come and Go, Eh Joe, Breath, Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio,…but the clouds…, A Piece of Monologue, Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Quad, Catastrophe, Nacht und Traume, What Where. Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life gives a short account of Beckett’s little-known private life in a book which is packed with rare photographs and shots of his stage productions. The life is quite surprising: a priviledged upbringing, with talented academic prospects which he abandonded for a bohemian life. Fighting with the Maquis during the war. Little artistic success, but lots of relationships with women – and then the big breakthrough with Waiting for Godot. This is a stunning little book.

Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life gives a short account of Beckett’s little-known private life in a book which is packed with rare photographs and shots of his stage productions. The life is quite surprising: a priviledged upbringing, with talented academic prospects which he abandonded for a bohemian life. Fighting with the Maquis during the war. Little artistic success, but lots of relationships with women – and then the big breakthrough with Waiting for Godot. This is a stunning little book.