Frankfurt – Vienna – Berlin

The first volume of Elias Canetti’s remarkable memoirs ended in early 1920 when his mother plucked him out of what she regarded as his self-indulgent intellectual reveries in Zurich, and dragged him into inflation-torn Germany to face ‘real life’. That’s where the story is taken up here – in a Frankfurt boarding house in 1921. The Torch in My Ear continues the very Oedipal relationship with his widowed mother and reaches the point where he must decide on a career. He shifts again to Vienna and begins to study Chemistry, quite clearly without any genuine appetite for the subject.

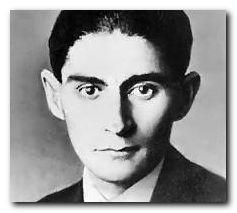

In all his activities there’s a remarkable degree of similarity with the life which Franz Kafka was leading in nearby Prague – restless moving from one temporary home to another, outdoor swimming and walking, psychological struggles with a dominant parent, and aesthetic aspirations as an antidote to the tedium of daily life.

In all his activities there’s a remarkable degree of similarity with the life which Franz Kafka was leading in nearby Prague – restless moving from one temporary home to another, outdoor swimming and walking, psychological struggles with a dominant parent, and aesthetic aspirations as an antidote to the tedium of daily life.

These similarities are intensified in one or two completely bizarre scenes where Canetti stumbles upon an elderly woman flogging a housemaid who is stripped to the waist in a kitchen, and then later encounters his landlady late at night licking the backs of paintings of her late husband. Later in the memoir he makes friends with a young man who is completely paralysed, but with whom he has conversations about philosophy. These scenes might have come straight from a work by Kafka.

A major influence on his life in Vienna was Karl Kraus, author of the one-man newspaper Die Fackel (The Torch) which gives this volume its title in German – Die Fackel im Ohr – though he does not give an account of Kraus’s ideas, so much as his charisma as a public speaker.

Canetti’s personal life is dominated by a deeply literary friendship with a young woman called Veza, but it is characteristic of his approach to autobiography that his account of the relationship is completely intellectualized. He reveals absolutely nothing about the state of his feelings for the girl, and she disappears from the narrative without trace, as does even his mother.

You would never guess from this volume of the memoirs that Veza developed a literary career of her own, and eventually became his wife. Neither would you guess that she also had a relationship with his younger brother Georges – or that she only had one arm.

On the 15 July 1927 in Vienna (known as Black Friday) the police shot dead eighty-four protesters in a demonstration against the government. The Palace of Justice was set alight, and there were riots in the streets – in all of which Canetti was caught up. This he depicts as one of his life-forming experiences, and he devoted the next thirty years or more to the study of mass psychology that resulted in his book Crowds and Power (1960).

Given that he wrote these memoirs fifty years and more after the events described, he has an astonishing memory for names, places, and the fine details of everyday life. Characters are brought into being on the page almost as if they were people he had encountered the day before. The downside of this approach is that the memoir becomes predominantly a series of anecdotal sketches – a boastful dwarf; a one-legged Mormon; a beautiful Russian girl who lives via Dostoyevski. But he doesn’t bother to relate any of these characters to any larger social or artistic issues.

When he does escape from describing characters to presenting general reflections on life, he often drifts into a sort of rambling which seems to combine narrative via metaphor with a form of German metaphysics:

Far more important was the fact that you were simultaneously learning how to hear. Everything that was spoken, anywhere, at any time, by anyone at all, was offered to your hearing, a dimension of the world that I had never had any inkling of. And since the issue was the combination—in all variants—of language and person, this was perhaps the most important dimension, or at least the richest. This kind of hearing was impossible unless you excluded your own feelings. As soon as you had put into motion what was to be heard, you stepped back and only absorbed and could not be hindered by any judgement on your part, any indignation, any delight. The important thing was the pure unadulterated shape: none of these acoustic masks (as I subsequently named them) could blend with the others For a long time you weren’t aware of how great a supply you were gathering.

His account moves up a gear when he visits Berlin in 1928 at the invitation of poetess Ibby Gordon. He meets most of the major artistic figures of the period – the montage artist John Heartfield (real name Helmut Herzfeld) his brother Wieland, the playwright Bethold Brecht, artist George Groz, and his favourite character the Russian writer Isaac Babel.

Some chapters are based on small incidents described in a puzzling degree of detail. At one point a conversation in a tavern with a group of criminals is expanded for several pages into minute descriptions of a burglar’s face and longwinded accounts of Canetti’s thoughts and feelings during the conversation. He has a personal theory of memory to explain this unusual approach – but it’s hard to know if this is just an excuse to cover his tracks:

I had seen many things in Berlin that stunned and confused me. These experiences have been transformed, transported to other locales, and, recognisable only by me, have passed into my later writings It goes against my grain to reduce something that now exists in its own right and to trace it back to its origin. This is why I prefer to cull out only a few things from those three months in Berlin—especially things that have kept their recognisable shape and have not vanished altogether into the secret labyrinth from which I would have to extricate them and clothe them anew. Contrary to many people, particularly those who have surrendered to a loquacious psychology, I am not convinced that one should plague, pester, and pressure memory or expose it to the effects of well-calculated lures; I bow to memory, every person’s memory

This seems to be a convoluted way of saying that he is only going to write about things that suit him, and there is certainly no attempt here to create a continuous picture of either his own intellectual development, or the artistic current of the times through which he lived. Indeed, as Clive James has argued in his own excellent review of this volume, Canetti’s ego was so overwhelming that it actually prevented him empathising with other people.

© Roy Johnson 2012

Elias Canetti, The Torch in my Ear, London: Granta Publications, 2011, pp.384, ISBN: 1847083579

![]() Volume One of the memoirs — The Tongue Set Free

Volume One of the memoirs — The Tongue Set Free

![]() Volume Two of the memoirs — The Torch in My Ear

Volume Two of the memoirs — The Torch in My Ear

![]() Volume Three of the memoirs — The Play of the Eyes

Volume Three of the memoirs — The Play of the Eyes

![]() Volume Four of the memoirs — Party in the Blitz

Volume Four of the memoirs — Party in the Blitz

Twentieth century literature

More on biography

From his earliest years he produced book reviews, essays, lectures, film reviews, prologues, and translations in addition to his now-famous fictions. He even invented literary genres – the essay which is part philosophic reflection and part fiction; studies of imaginary works; and biographies of people who did not exist. This in addition to spoofs, mind games, and metaphysical writings of a kind that seem to transcend national boundaries – which is partly why he managed to establish his international reputation.

From his earliest years he produced book reviews, essays, lectures, film reviews, prologues, and translations in addition to his now-famous fictions. He even invented literary genres – the essay which is part philosophic reflection and part fiction; studies of imaginary works; and biographies of people who did not exist. This in addition to spoofs, mind games, and metaphysical writings of a kind that seem to transcend national boundaries – which is partly why he managed to establish his international reputation.

K is visited by his uncle, who is a friend of a lawyer. The uncle seems distressed by K’s predicament. At first sympathetic, he becomes concerned K is underestimating the seriousness of the case. The uncle introduces K to an advocate, who is attended by Leni, a nurse, who K’s uncle suspects is the advocate’s mistress. K. has a sexual encounter with Leni, whilst his uncle is talking with the Advocate and the Chief Clerk of the Court, much to his uncle’s anger, and to the detriment of his case.

K is visited by his uncle, who is a friend of a lawyer. The uncle seems distressed by K’s predicament. At first sympathetic, he becomes concerned K is underestimating the seriousness of the case. The uncle introduces K to an advocate, who is attended by Leni, a nurse, who K’s uncle suspects is the advocate’s mistress. K. has a sexual encounter with Leni, whilst his uncle is talking with the Advocate and the Chief Clerk of the Court, much to his uncle’s anger, and to the detriment of his case.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis Amerika

Amerika Studying Fiction

Studying Fiction

To the Lighthouse

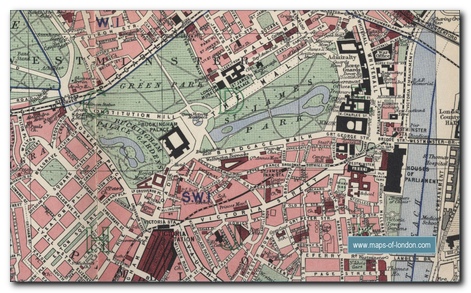

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

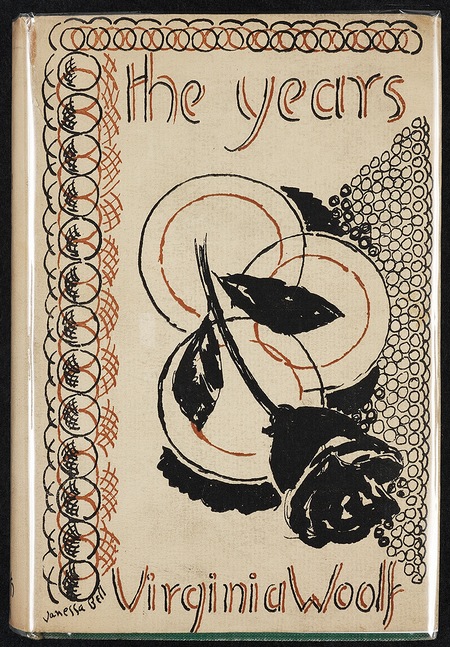

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Thomas Mann’s work spans the first half of the twentieth century. He started out writing in the tradition style of the nineteenth centry, but very quickly sought out themes and motifs which place him amongst modernists. His political views went through a similar transformation, from arch conservative before and during the first world war, to a very sceptical liberal democracy after the second. Many of his works are long and dense, and his style includes such typically Germanic features of writing in huge paragraphs, with lots of philosophic meditation embedded in his narratives. Beginners are best advised to sart with his earlier work – particularly novellas such as

Thomas Mann’s work spans the first half of the twentieth century. He started out writing in the tradition style of the nineteenth centry, but very quickly sought out themes and motifs which place him amongst modernists. His political views went through a similar transformation, from arch conservative before and during the first world war, to a very sceptical liberal democracy after the second. Many of his works are long and dense, and his style includes such typically Germanic features of writing in huge paragraphs, with lots of philosophic meditation embedded in his narratives. Beginners are best advised to sart with his earlier work – particularly novellas such as  Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family

Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family Death in Venice

Death in Venice Death in Venice – video film adaptation

Death in Venice – video film adaptation The Magic Mountain

The Magic Mountain Doktor Faustus

Doktor Faustus Mario and the Magician

Mario and the Magician Thomas Mann: a life This exploration of Thomas Mann’s life by Donald Prater describes his relationship of intense rivalry with his brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist, his (much-concealed) homosexuality, his career as a prolific essayist, and the vast achievement of his novels. Particular attention is paid to Mann’s opposition to Nazism, and his role in the rise and fall of Hitlerism. It traces Mann’s political development from the nationalistic conservatism of his younger days, to the humanistic anti-Nazim of his maturity.

Thomas Mann: a life This exploration of Thomas Mann’s life by Donald Prater describes his relationship of intense rivalry with his brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist, his (much-concealed) homosexuality, his career as a prolific essayist, and the vast achievement of his novels. Particular attention is paid to Mann’s opposition to Nazism, and his role in the rise and fall of Hitlerism. It traces Mann’s political development from the nationalistic conservatism of his younger days, to the humanistic anti-Nazim of his maturity.