a short biography, video presentation & further reading

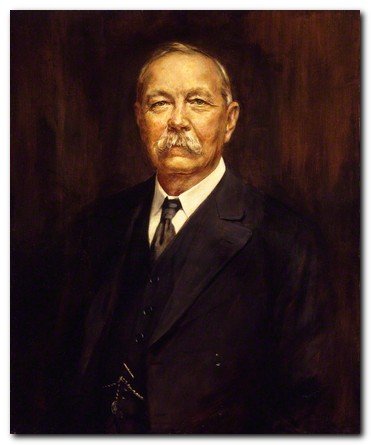

Arthur Conan Doyle was born in 1859 in Edinburgh and educated at Stonyhurst College in Lancashire – a public school run by Jesuits (alumni include Gerard Manley Hopkins and J.R.R. Tolkien). From there he went back to Edinburgh University to study medicine, meeting in the process Doctor Joseph Bell, a consulting surgeon whose powers of deduction and induction were later used as the basis for the creation of Sherlock Holmes. He also began to develop a youthful enthusiasm for writing around this time. In 1880 he signed on as ship’s surgeon on an Arctic whaling expedition, then after returning several months later, completed his degree and sailed off again, this time to Africa.

He set up his first practice as a doctor in Portsmouth, and in the long periods spent waiting for patients wrote stories which were published anonymously. In 1885 he married the sister of one of his patients and the year after wrote the book in which Sherlock Holmes made his first appearance – A Study in Scarlet. He went on to write historical romances, but when more Sherlock Holmes stories appeared in The Strand Magazine and became increasingly popular, he gave up medicine to become a professional author.

The Sherlock Holmes phenomenon made his fame and fortune, but because he thought of himself as a ‘serious novelist’ he killed off his by now famous detective hero by having the villainous Professor Moriarty pull him to his death over the edge of the Reichenbach falls in the appropriately named story The Final Problem.

Conan Doyle travelled widely in America, Egypt, and South Africa, working for a time as a doctor in the Boer War. In 1902 he was knighted by Edward VII for his enthusiastic contribution to the English war against the Boers.

Meanwhile the success of the Sherlock Holmes stories in America brought a renewed and very profitable demand for more. As a first move he wrote one of his best Holmes pieces – The Hound of the Baskervilles – but set it at a time before the supposed demise of his hero. However, the book was such an huge success that he was forced to resurrect Holmes completely, and he went on to write another series of the stories – though devotees of the cult claim that these are not quite so skilfully crafted as their predecessors.

Conan Doyle became a public figure and gave his name to a number of different causes. He stood for parliament on two occasions – both times unsuccessfully. He took up the cases of people he felt had been unjustly treated by the law. Most controversially, he gave money and time to advance the case of spiritualism.

In 1912 he published his second most successful work that does not include Sherlock Holmes – The Lost World. This was a novel of adventure featuring a prehistoric world of dinosaurs and mammoths discovered in the jungles of South America.

During the period 1914-1918 he occupied himself producing patriotic tracts, wrote a six-volume history of the war, and gradually transferred most of his attention to works of non-fiction. Then during the last fifteen to twenty years of is life he devoted himself almost entirely to the promotion of spiritualism.

At that time the phenomenon was in its heyday of seances in which the dead were summoned back to life at public meetings, psychic mediums extruded ectoplasm from their mouths, and photographs of ghosts and fairies were seriously offered as evidence of a hidden spirit world.

Despite the fact that these events were exposed as frauds by Harry Houdini – the escapologist he met and befriended in 1920 – Conan Doyle continued in his blind belief and damaged his public reputation with publications such as The Coming of the Fairies (1922). In his last years he toured Australia, the United States, and Scandinavia, preaching the spiritualist cause. When he died in 1930 his grave was inscribed:

STEEL TRUE

BLADE STRAIGHT

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

KNIGHT

PATRIOT, PHYSICIAN, MAN OF LETTERS

Arthur Conan Doyle – further reading

![]() The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Sherlock Holmes – Penguin – Amazon UK

The Complete Sherlock Holmes – Penguin – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Sherlock Holmes – Penguin – Amazon US

The Complete Sherlock Holmes – Penguin – Amazon US

![]() The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Wordsworth – Amazon UK

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Wordsworth – Amazon UK

![]() The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Wordsworth – Amazon US

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Wordsworth – Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2016

More 19C Authors

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.