tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

Pandora (1884) is a story which combines three topics which regularly fascinated Henry James and are present in many of his tales and novels. Foremost is the relationship between Europe and America – his ‘International’ theme. Next comes the ‘new woman’ who emerged in America towards the end of the nineteenth century and behaved in a socially more liberated manner. And third is the social and moral tensions which arise in cases of class mobility – though James doesn’t always discuss this issue explicitly.

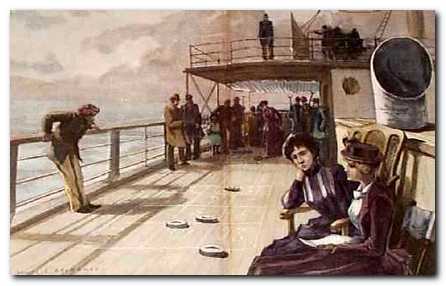

Nineteenth century transatlantic steamer

Its textual history throws an interesting light onto the publishing of fiction in the late nineteenth century. It first appeared in two instalments of the New York Sun on 1 and 8 June 1884. That’s a week between each part of the story – rather like a television drama today. It was then reprinted twice in book form, collected with other Henry James stories. This is a form of publication almost unthinkable today. Then, when James was honoured with the multi-volume New York edition of his collected works, it appeared again, heavily revised.

Pandora – critical commentary

The ‘new woman’

James presents Pandora as an example of the ‘new type’ of woman, the ‘self-made girl’ – but she is in fact a product of upward social mobility – an arriviste. She comes from a family in trade, not people of inherited wealth or ‘old money’ upper-class society to which she aspires. She is intent on prising the family away from their provincial origins of Utica in upper New York state, of which Mrs Dangerfield observes “You can’t have a social position in Utica any more than you can have an opera box”. In fact she adds that Pandora (by Mrs Dangerfield’s own standards) does not even have a ‘social position’. Yet she is on the way to acquiring one.

It is interesting to note that her fiancé Bellamy is also originally from the same upstate town, and he too started out in ‘some kind of business’ with not enough income to offer her marriage. They have been engaged since Pandora was sixteen. But he too has managed to climb upwards socially with his appointment to a diplomatic position in government.

To reinforce the argument that this is a class mobility issue, there is a strong suggestion that Bellamy has secured his appointment via Pandora’s influence during her conversation with the president of the ‘the world’s largest country’ [James’s words]. At the social gathering where she meets the president she takes her leave of him by saying “Well now, remember, I consider it a promise”.

Narrative structure

The story is neatly divided into two parts – each of which reflects the other. In the first part Vogelstein gets to know Pandora whilst on board a ship. When it docks she is due to be met by her fiancé Bellamy, but he is unavailable. In the second part they are again on board a river boat, but this time Bellamy does make his appearance to claim his bride-to-be.

At the start of part one, Vogelstein has just been appointed to the German legation in Washington – and so has travelled from Europe to America. At the end of part two, Bellamy has been appointed as ambassador to Holland – and will therefore be travelling from America to Europe to take up his post.

Inter-textuality

This is very much a conscious variation on the theme of the ‘new type’ of woman from James’s earlier success, Daisy Miller – so much so that he has his protagonist and narrator Vogelstein actually reading the story on board ship whilst journeying to New York – in a German pocketbook edition. He comments on the characters in the story and draws comparisons between Daisy and Pandora, as well as between Randolph Miller and Pandora’s brother, who he sees as what the young Randolph might have grown up to become.

there was for Vogelstein at least an analogy between young Mr.Day and a certain small brother … who was, in the Tauchnitz volume, attributed to that unfortunate maid. This was what the little Madison [Randolph] would have grown up to at nineteen, and the improvement was greater than might have been expected

Name and title

The Pandora of classical Greek mythology was the name for the first ‘all gifted’ woman, created by Zeus (King of the Gods) for the deliberate confusion of man. She was sent as a wife to Epimetheus with a box which she was forbidden to open. When she disobeyed this injunction, she released all the evils of the world. Only Hope remained inside the box.

It is not difficult to see these meanings linked to the repeated appearance of strong women in James’s stories as predatory creatures who might threaten men who have a fear of marriage. Vogelstein certainly perceives Pandora as an aggressive female, putting her into that category with other women he has encountered ‘they were apt to advance, like this one, straight upon their victim’.

It is also perhaps worth noting that Pandora is not her real but her ‘pet’ name. Just like the socially mobile Daisy Miller, whose real name is Annie P. Miller, Pandora is shedding part of her provincial identity as she climbs upwards. We do not learn her real name.

Pandora – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() Pandora – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Pandora – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Pandora – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

Pandora – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Pandora – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

Pandora – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Pandora – plot summary

Part I. Count Otto Vogelstein has just been appointed as secretary to the German legation in Washington. He is travelling from Southampton to New York on board the steamship Donau when he meets Pandora Day, a spirited young American woman and her family. Because of his lack of experience and his rather conventional social views, he is unable to place her socially. Mrs Dangerfield, an experienced American fellow traveller, warns him against closer acquaintance on the grounds that the family lack the necessary social cachet.

Part II. Two years later he meets Pandora again at an exclusive society party in Washington which includes the American president. She has become even more attractive and socially confident. The hostess describes her to Vogelstein as a woman of a ‘new type’. He wonders what this type can be, and is told that it is an exclusively American phenomenon of a younger woman developing upward social mobility as a result of reading, natural talent, and foreign travel.

Part II. Two years later he meets Pandora again at an exclusive society party in Washington which includes the American president. She has become even more attractive and socially confident. The hostess describes her to Vogelstein as a woman of a ‘new type’. He wonders what this type can be, and is told that it is an exclusively American phenomenon of a younger woman developing upward social mobility as a result of reading, natural talent, and foreign travel.

Vogelstein joins Pandora on a boating party up the Potomac river to the home of George Washington and feels himself drawn closer to her – even entertaining ideas of her qualities as a diplomat’s wife. However, he is cautious because he thinks she might be a pushy spouse, and might commit social gaffes in his aristocratic German social circles. However, on landing back in Washington, she is met by a man who turns out to be her long term fiancé who has just been appointed as American ambassador to Holland.

Principal characters

| Count Otto Vogelstein | a young man in the German diplomatic service |

| ‘Pandora’ Day | a young American woman |

| Mr P.W. Day | her father from Utica in upstate New York |

| Mrs Day | her mother |

| Mrs Dangerfield | Vogelstein’s American confidante on board the Donau |

| Mr D.F. Bellamy | Pandora’s fiancé from Utica (40) |

| Mr Lansing | Bellamy’s friend, an immigration officer in New York |

| Mrs Bonnycastle | social hostess and arbiter in Washington |

| Mr Alfred Bonnycastle | her husband |

| Mrs Steuben | a widow |

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

© Roy Johnson 2012

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Patrick White was born in Australia but sent to be educated in England, which he disliked intensely. He settled to live in London during the 1930s and served in the RAF during the war. After the war he returned to live in Australia, eking out his small private income by farming. His novels offer great variety in their themes, subjects, and settings – but what they have in common is his use of powerfully rich language, his deeply psychological character portraits, the dramatic incidents of his stories, and a semi-mystical belief system which he invites us to contemplate without making his narratives depend upon it. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973.

Patrick White was born in Australia but sent to be educated in England, which he disliked intensely. He settled to live in London during the 1930s and served in the RAF during the war. After the war he returned to live in Australia, eking out his small private income by farming. His novels offer great variety in their themes, subjects, and settings – but what they have in common is his use of powerfully rich language, his deeply psychological character portraits, the dramatic incidents of his stories, and a semi-mystical belief system which he invites us to contemplate without making his narratives depend upon it. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973.

Between the Acts

Between the Acts The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth The Reef

The Reef