tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

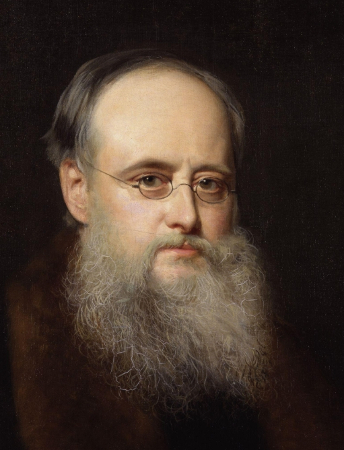

The Moonstone (1868) is often regarded as the first great detective novel. It is certainly a great novel of mystery that sustains both its central puzzle and the solution to it over a very long narrative. The book is also a ‘sensation novel’ – one that sets out to deliberately shock the reader. This was a genre of fiction in which Wilkie Collins excelled. He was a friend and a collaborator of Charles Dickens, and one of the most commercially successful novelists of the mid nineteenth century.

The Moonstone – a note on the text

The Moonstone first appeared as weekly instalments in All the Year Round, the literary magazine owned and edited by Charles Dickens, the friend and sometimes collaborator of Wilkie Collins. Before the serialization had reached its conclusion, it was published in what was then the conventional three volume format by William Tinsley, and in single volume format later the same year.

Although the book did not at first sell well in novel format, it eventually became Collins’ second most successful work, after The Woman in White.

For a full account of the composition, publication and reception of the novel, see the bibliographic essay by John Sutherland in the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Moonstone.

The Moonstone – critical commentary

The narrative

Wilkie Collins adopted the same narrative strategy as he had for his previous big success The Woman in White – a multiplicity of voices. They are multiple both in their literary style and their various points of view. This makes the reader’s task more difficult in assembling a ‘truth’ of what happens in the story, but it offers more entertainment as a compensation.

The narrators include Gabriel Betteredge a longwinded house steward,;Franklin Blake the apparent hero of the novel; Drusilla Clack an interfering spinster; Sergeant Cuff a Scotland Yard detective who guesses the identity of the villain; and Ezra Jennings, a curious medical assistant who actually solves the mystery.

Gabriel Betteredge’s narrative is styled as a combination of his favourite reading – Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe – and another eighteenth century monologuist, Laurence Sterne. Betteredge goes into enormous detail over inconsequential trivialities, and he offers long irrelevant digressions, meanwhile passing flattering comments on his own approach as a raconteur of events.

His explanations of what has taken place mean that the story often goes backwards to fill inn the provenance of characters and what has already happened. He is driven to address the reader, pleading for patience, and offering promises that before long the story will be going forwards to get to the point he has been tasked with addressing.

Betteredge also changes his written style to suit the events he is describing. For instance, he gives an account of his daughter Penelope’s police interview in the form of a constable’s abbreviated notes – lapsing comically into longwinded irrelevancies and self-reference. (Betteredge frequently compliments himself as a gifted sleuth: he describes himself as being overcome with ‘the detective fever’.)

Penelope examined. Took a lively interest in the painting on the door, having helped to mix the colours. Noticed the bit of work under the lock, because it was the last bit done. Had seen it some hours afterwards, without a smear … dress recognised by her father as the dress she wore that night, skirts examined, a long job from the size of them, not the ghost of a paint-stain discovered anywhere. End of Penelope’s evidence – and very pretty and convincing too. Signed, Gabriel Betteredge.

Multiple narrators

Collins’ strategy of using multiple narrators produces some other amusing characters – such as the appalling shrew Drusilla Clack, who tyrannises the other characters with her ‘improving’ religious tracts on Satan in the Hair Brush. But this approach does have its weaknesses. There is sometimes unnecessary repetition when one character gives an account of events which are already known to reader, without adding anything new.

A larger weakness is that there is sometimes no explanation given for the source of the information. When Godfrey Ablewhite is exposed as the Diamond thief, Sergeant Cuff gives an account of his villainous embezzlement, his lavish villa in the suburbs, and his secret mistress – but there is no explanation of how he has obtained this information or why it could not have been known before.

Added to that, there are minor problems of scrappiness generated by the number of different narrators towards the end of the story, and unexplained issues such as the identity of the author of the prologue, and no really convincing justification for Murthwaite’s final missive describing the restitution of the Diamond in India.

The sexual interpretation

It is not difficult to see that the central incident of the Diamond theft has distinctly sexual overtones. The moonstone has been given to Rachel on her eighteenth birthday – acting as both a symbol of her virginity and an emblem of her ‘coming-of-age’ at the same time. As the literary critic John Sutherland observes, in eastern religions, gemstones were often placed in the ‘Yoni’ (the vagina) of female statues.

Franklin and Rachel are amorously attracted to each other, and (controversially for that period) are both in her bedroom late at night when the Diamond disappears. Franklin takes the stone from a drawer in her cabinet, with the result that he has a stain (semen? hymenal blood?) on his nightgown. Both parties are awake at the time – though he has been drugged.

The stained nightgown is then confiscated by the maid Susanna Spearman, who is passionately in love with Franklin and quite rightly sees Rachel as rival for his affections. Not only that, but she inspects his bedroom and finds further stains on the inside of his dressing gown: As she writes to him later:

My head whirled round, and my thoughts were in a dreadful confusion. In the midst of it all, something in my mind whispered to me that the smear on your nightgown might have a meaning entirely different to the meaning which I had given to it up to that time.

She is conflicted over her possession of the soiled nightgown, unsure if it will be useful for her love or her revenge. In the end she buries the nightgown in an effort to protect Franklin from detection. But this symbolically blots from her consciousness the evidence of his sexual connection with another woman. She replaces it with a new, unsullied nightgown of her own making, thus preserving an unstained image of him in her own mind. Shortly afterwards she commits suicide.

The detective novel

The poet T.S.Eliot once described The Moonstone as ‘the first and the greatest of English detective novels’ – an endorsement which has been blazoned across the covers of many paperback editions ever since. Yet it is not the first detective novel: Dickens published Bleak House sixteen years previously in 1852, which included his famous sleuth figure, the sardonic Inspector Bucket. Whether it is the ‘greatest’ detective novel is open to debate – a debate for which Eliot does not offer any evidence or make a case.

Moreover, it is not really a detective story, so much as a mystery story – and this despite featuring not one but two detectives amongst its characters. The first of these, local officer Superintendent Seegrave, misinterprets the situation, makes a hash of gathering evidence, and fails to solve the problem. The second detective, Sergeant Cuff from Scotland Yard, is more perceptive and he does eventually predict the identity of the villain correctly – but he fails to recover the Diamond.

The mystery is actually solved by an outsider – the tragic and piebald medical assistant Ezra Jennings, who is an opium addict. It is he who correctly ‘interprets’ the delirious ramblings of his employer Thomas Candy. He then proposes the experiment of unlocking Franklin’s memory of exactly what happened the night the Diamond was stolen by repeating the dose of laudanum he had secretly been given. Jenning’s surmise and his experiment are both successful – and the remainder of the novel is a frantic pursuit to re-capture the Diamond, which fails completely.

The double

In her biography of the author, Catherine Peters observes that ‘All his life, Wilkie Collins was haunted by a second self”:

When he worked late into the night, another Wilkie Collins appeared: ‘… the second Wilkie Collins sat at the same table with him and tried to monopolise the writing pad. Then there was a struggle … when the true Wilkie awoke, the inkstand had been upset and the ink was running over the writing table. After that Wilkie Collins gave up writing at nights.

There is certainly a very striking example of what we now call ‘the double’ at work in The Moonstone. When the assistant doctor Ezra Jennings is introduced, the description of him (given by Franklin) emphasises his peculiar appearance. He has a ‘gypsy complexion’, ‘fleshless cheeks’, and appears simultaneously old and young. Most peculiar of all, he is piebald – with hair that is distinctly black and white.

Yet he and the handsome Franklin are immediately and inexplicably drawn to each other. Franklin finds that ‘Ezra Jennings made some inscrutable appeal to my sympathies, which I found it impossible to resist’. Jennings for his part confesses ‘There is no disguising, Mr Blake, that you interest me’.

Franklin is rich and handsome: Jennings is an outcast with a guilty secret in his past. Both of them are burdened by a misdemeanour, and neither of them are capable of proving their innocence. Jennings has a stain on his reputation as a human being, and Franklin a stain on his clothes that brands him as a thief. Moreover, both of them are drug addicts.

Franklin is addicted to tobacco. When he stops smoking cigars he cannot sleep and is reduced to a nervous wreck, grappling with the temptation of his cigar cabinet. Jennings is an opium addict – a habit originally taken up to ease the pain of some unspecified ailment, but now a simple dependence on the narcotic.

The two characters, as with many examples of the double, are like two parts of the same being, twins yet opposites. Franklin is rich, handsome, and rising in society. Jennings is broken, haunted by his past sin (which is not specified) and sinking fast under the effects of his addiction.

Yet Jennings is sinking in a noble manner. Knowing that he will soon die, he is working hard to leave money to someone he loves. He feels grateful for the mere fact that Franklin shows him toleration and friendship:

You, and such as you, show me the sunny side of human life, and reconcile me with the world that I am leaving, before I go … I shall not forget that you have done me a kindness in doing that.

Jennings saves Franklin’s social reputation by proving his innocence. In doing so he restores the relationship between Franklin and Rachel. His interpretation of events is superior to that of the professional sleuths, Seegrave and Cuff. And in the end he dies a tragic hero, wishing to be forgotten in an unmarked grave.

The sensation novel and its credibility

The sensation novel was ‘a novel with a secret’ and for the first three quarters of The Moonstone the secret of the whole drama is that the person who stole the Diamond from Rachel Verinder’s bedroom is none other than the apparent hero of the novel – Franklin Blake.

This incident sets in train a whole host of sub-mysteries and red herrings about who the guilty person might be, and how the mysteries can be unravelled, the crime solved, and the Diamond recovered.

But it has to be said that Wilkie Collins, for all his inventiveness, puts a great strain on the reader’s credulity in forging the links in his plot. The fact that Franklin was acting under the influence of a secretly administered dose of opium when he stole the Diamond is difficult enough to accept as an explanation of three hundred pages of mystery and drama.

But then we are asked to believe that whilst in the act of taking the Diamond (all the time observed by his lover Rachel) he then unconsciously gives the Diamond to the villain of the piece (Godfrey) who has been watching him secretly from a room next door. This pushes the plotting of the novel into the realms of over-contrived melodrama.

These events concern what the novel’s contents page describe as ‘The Loss of the Diamond’ but in the latter part of the novel (‘The Discovery of the Truth’) there are similar demands made of the reader’s credulity. First the opium experiment proposed by Ezra Jennings manages to miraculously repeat the exact sequence of events that took place on the night of the theft – thus proving Franklin’s innocence.

Well – that might be explained as an essay in ‘released memory’ or ‘the workings of the unconscious’ – a quasi-scientific approach to interpretation reflecting the mid-nineteenth century understanding of psychology. But when the location of the Diamond is discovered (which rounds off the story quite nicely) Collins pushes the levels of contrivance to unacceptable lengths. We are expected to believe the following sequence of events.

First, that the Indian vigilantes are able to gain access to the roof of “The Wheel of Fortune” tavern where Godfrey is hiding, disguised as a sailor. Fortunately for dramatic purposes, a builder’s ladder has been left conveniently available nearby. Next, once on the roof, they are able to cut through a trapdoor (using an ‘exceedingly sharp instrument’) then drop into the room – without once disturbing the occupant. They then kill the thief (Godfrey) without making any sound, and are able to climb back out through the trapdoor, which is seven feet above them. How do they manage this? By using yet another ladder which is kept under the bed – for regular use by customers.

It’s fortunate that The Moonstone has many other successful features of characterisation, narration, and design; because without these literary qualities, the improbabilities and unconvincing elements of ‘sensation’ plotting would sink the novel completely.

The Moonstone – study resources

![]() The Moonstone – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

The Moonstone – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Moonstone – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

The Moonstone – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Moonstone – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Moonstone – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Moonstone – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Moonstone – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Moonstone – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

The Moonstone – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Moonstone – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

The Moonstone – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Moonstone – Study Notes – Amazon UK

The Moonstone – Study Notes – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Wilkie Collins – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Wilkie Collins – Kindle eBook

![]() The Moonstone – 2009 BBC film

The Moonstone – 2009 BBC film

The Moonstone – plot summary

Prologue

1799 – The Moonstone is looted by Colonel John Herncastle during the storming of Serangapatan in India.

First Period – The Loss of the Diamond

1848 The aged house steward Gabriel Betteredge is asked to begin the narrative concerning the loss of the diamond. There is a visit to the house by three Indian ‘conjurers’. Betteredge talks to the morbid maid Rosanna on the Shivering Sand. Spendthrift Franklin Blake returns home from his education in Europe – in possession of the diamond, which has been left to Rachel Verinder in the Colonel’s will.

The Colonel has visited Lady Verinder on Rachel’s birthday, but has been turned away from the house. Franklin Blake reports the Colonel’s arrangements for his will and goes to put the Diamond in a local bank until Rachel’s next birthday.

Franklin and Rachel go in for decorative door painting. The maid Rosanna is in love with Franklin. Philanthropist and ladies’ man Godfrey Ablewhite is invited to Rachel’s party. The Diamond is presented to Rachel, who then refuses an offer of marriage from Godfrey. During dinner there is a visit from the Indians. By next morning the Diamond has disappeared.

Superintendent Seegrave arrives to interview staff and guests, with no result. Rosanna has the vapours over Franklin and behaves strangely. Franklin sends to London for more experienced help.

Sergeant Cuff arrives from Scotland Yard, establishes the paint smear on a door as an important clue, and then claims the Diamond has not been stolen. Cuff wishes to inspect everyone’s clothes in pursuit of the paint smear – but Rachel refuses to comply.

Cuff pays special attention to Susanna because of her erratic behaviour. Betteredge and Cuff visit the Shivering Sand, then Susanna’s friends in a fisherman’s cottage. Cuff believes Susanna has sunk something in the sands.

When they get back to the house, Rachel wants to leave. Cuff has a theory that she has the Diamond. Susanna seems on the edge of making a confession, but doesn’t. Cuff thinks that Susanna has made a new nightdress and hidden the one with a paint smear. Rachel leaves the house and Susanna seems to be plotting to retrieve her hidden nightdress.

When Susanna disappears a fruitless search is made of the Shivering Sand, followed by the discovery of her suicide note. Lady Verinder thinks to dismiss Cuff, who argues that Rachel probably has secret debts and has engaged Susanna as an accomplice in selling the Diamond. Lady Julia challenges Rachel with these claims, but she denies all the charges – so Cuff is paid off.

Lady Verinder takes Rachel to London. Franklin leaves for Europe, and Limping Lucy Yolland accuses him of ruining Susanna’s life. Cuff’s three predictions regarding the Yollands, the Indians, and the money-lender all come true.

Second Period – The Discovery of the Truth

Miss Clack gives an account of Godfrey Ablewhite being decoyed in London and searched by three Indians. The same thing happens to Mr Luker. Rachel is upset by the news. She interrogates Godfrey and insists on his innocence against rumours that he is in league with Luker.

Lady Verinder reveals that she has heart problems. Clack and lawyer Bruff discuss Rachel, Godfrey, and Franklin as possible suspects. Clack leaves improving books with Julia, all of which are returned unread – so she posts letters containing quotations. She overhears Godfrey proposing to Rachel, who is conflicted but accepts. Lady Verinder suddenly dies.

The Ablewhites and Rachel move to Brighton accompanied by Clack who vows to ‘interfere’. Rachel retracts her engagement to Godfrey, who accepts the rejection, but his father reproaches Rachel and refuses to be her guardian. Clack wants to read sermons and is rejected by everyone. Rachel leaves under the protection of family lawyer Bruff.

Bruff reveals that Godfrey has asked to see Sir John Verinder’s will, which limits Rachel’s inheritance. Godfrey has accepted Rachel’s rejection because he needs a ‘large sum of money’. Bruff is visited by the suave Indian who has also been to see Luker, asking how soon a loan must be repaid. Murthwaite advances a theory that explains the Indians’ plot to retrieve the Diamond, which has been handed to Luker.

Franklin returns to England on the death of his father (having inherited a substantial fortune). Rachel refuses to see him. He thinks it’s because of the Diamond, so he goes to Yorkshire to take up the search where it was left off. Betteredge helps him to recover the letter left for him by Susanna. The letter gives him instructions for recovering the nightgown hidden in the Shivering Sand.

Rosanna has also left a long letter, explaining her love for Franklin and how she found the paint stain on his nightgown. She kept it, believing that he had stolen the Diamond to pay off heavy debts.

Franklin takes the evidence to Bruff in London, who agrees to arrange a meeting with Rachel. She reveals to Franklin that she saw him stealing the Diamond, and has concealed the fact ever since out of love for him. They part in great bitterness. Franklin goes to Yorkshire in search of the birthday dinner guests. Mr Candy wants to tell him something, but cannot remember what it is.

Ezra Jennings relates how he has nursed Mr Candy, and how his life has been ruined by a stain on his reputation. He is saving his small inheritance for a loved one and surviving the threat of death by taking opium. When Franklin reveals his own problem Jennings claims that his transcriptions of Candy’s delirious statements will prove Franklin was unconscious at the time the Diamond was stolen..

The notes reveal that Candy gave Franklin a dose of opium on the night of the party. Jennings also suggests that the Diamond might have been stolen from Franklin, so he proposes a repeat opium experiment to prove Franklin’s innocence.

Jennings writes to Rachel explaining the party trick on Franklin and asking for permission to use the Hall for a re-enactment. Rachel agrees and forgives Franklin. Bruff disapproves but agrees to attend. Betteredge gives reluctant consent.

The principals assemble at the Hall and the experiment is successful. Franklin takes the opium and removes a fake diamond from Rachel’s cabinet, but falls into a stupor before placing it in his own room.

Bruff and Franklin return to London where they see Luker at the bank. People who might have the Diamond are followed. A sailor is traced to a pub, but is dead next morning and turns out to be Godfrey Alblewhite.

Epilogue

Sergeant Cuff reports on the secret life of Ablewhite. He has stolen another man’s inheritance and spent it on a lavish villa where he keeps his mistress. Cuff reveals that Ablewhite was in the room adjacent to Franklin on the night of the party. Franklin, who had been drugged, asked Ablewhite to take the Diamond to his father’s bank for safe keeping.

Mr Candy reports on the death of Ezra Jennings. Franklin and Rachel are married. Cuff’s man traces the three Hindoos to a ship bound for Bombay. The captain reports that the Hindoos jumped ship whilst it was becalmed off the coast of northern India. Murthwaite’s letter records the return of the Diamond to its place in a shrine dedicated to Vishnu.

The Moonstone – principal characters

| Colonel John Herncastle | the original Diamond thief |

| Lady Julia Verinder | his sister |

| Rachel Verinder | Julia’s daughter |

| Franklin Blake | Jukia’s nephew |

| Matthew Bruff | the Verinder family lawyer |

| Gabriel Betteredge | elderly house steward to Lady Julia Verinder |

| Penelope | Betteredge’s daughter |

| Rosanna Spearman | housemaid, ex-reformatory, with deformed shoulder |

| Godfrey Ablewhite | a philanthropist and ladies’ man |

| Thomas Candy | the local doctor |

| Ezra Jennings | Candy’s piebald assistant |

| Mr Murthwaite | an explorer |

| Superintendant Seegrave | the local detective |

| Seargeant Cuff | a Scotland Yard detective |

| Drusilla Clack | a pious evangelical Christian |

| Septimus Luker | a money lender |

| Octavius Guy | Cuff’s boy detective assistant, ‘Gooseberry’ |

The Moonstone – further reading

William M. Clarke, The Secret Life of Wilkie Collins, London: Ivan R. Dee, 1988.

Tamar Heller, Dead Secrets: Wilkie Collins and the Female Gothic, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Winifred Hughes, The Maniac in the Cellar: Sensation Novels of the 1860s, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Sue Lonoff, Wilkie Collins and his Victorian Readers: A Study in the Rhetoric of Authorship, New York: AMS Press, 1982.

Catherine Peters, The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Walter C. Phillips, Dickens, Reade, and Collins: Sensation Novelists, New York: Library of Congress, 1919.

Lynn Pykett, Wilkie Collins: New Casebooks, London: Palgrave-Macmillan, 1998.

Nicholas Rance, Wilkie Collins and Other Sensation Novelists: Walking the Moral Hospital, London: Palgrave-Macmillan, 1991.

© Roy Johnson 2016

More on Wilkie Collins

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

Mrs Dalloway

Mrs Dalloway To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton