journalist, literary critic, and raconteur

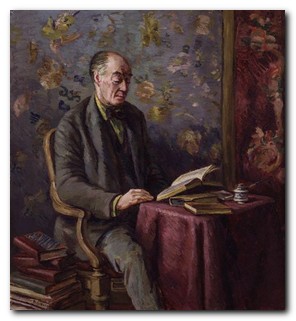

Desmond MacCarthy (full name Charles Otto Desmond MacCarthy) was born in Plymouth, Devon in 1877. He was educated at Eton College, the famous public (that is, private) school, and went on to Trinity College Cambridge in 1894. He became a close friend of G.E Moore, whose Principia Ethica had a profound influence on all those who went on to form the Bloomsbury Group.

He was older than the cohort of Leonard Woolf, Clive Bell, Saxon Sydney-Turner, and Thoby Stephen who all arrived later in 1899 – but because of his close friendship with Moore he re-visited frequently and formed friendships with the younger network. He was also a friend of Henry James and Thomas Hardy.

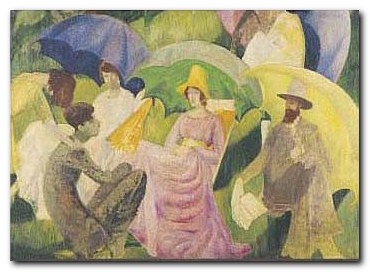

He married Mary (Molly) Warre-Cornish in 1906 and the next year edited The New Quarterly. Roger Fry asked him to become the secretary for the first Post-Impressionist exhibition he organised at the Grafton Galleries in 1910 – an event which Virginia Woolf described as of such significance that it changed human character. This gave MacCarthy the opportunity to tour Europe, buying paintings by Van Gogh, Cezanne, and Matisse, who at that time were relatively unknown.

During the first world war he served as an ambulance driver in France and he also spent some time in Naval Intelligence. He started writing reviews for the New Statesman in 1917 and went on to become its editor from 1920 to 1927. He wrote a weekly column under the nom de plume of ‘Affable Hawk’. After leaving the New Statesman he went on to be editor of Life and Letters and later succeeded Edmund Gosse as senior literary critic on the Sunday Times.

Although he was a professional man of letters who published a great deal of criticism, he was celebrated in the Bloomsbury Group as a brilliant raconteur and a creative writer of great promise. However, the promise never resulted in the production of the great novel he was always threatening to write. His gifts as a speaker are illustrated by a famous incident from a meeting of the Memoir Club, at which Bloomsbury members would give papers recalling past events and memoirs of fellow members. E.M. Forster recalls:

In the midst of a group which included Lytton Strachey, Virginia Woolf, and Maynard Keynes, he stood out in his command of the past, and in his power to rearrange it. I remember one paper of his in particular – if it can be called a paper. Perched away in a corner of Duncan Grant’s studio, he had a suit-case open before him. The lid of the case, which he propped up, would be useful to rest his manuscript upon, he told us. On he read, delighting us as usual, with his brilliancy, and humanity, and wisdom, until – owing to a slight wave of his hand – the suit-case unfortunately fell over. Nothing was inside it. There was no paper. He had been improvising.

In his autobiography Leonard Woolf, a friend and fellow editor, analyses the reasons for what he sees as the failure of Desmond MacCarthy to fulfil his promise as a creative writer. He acknowledges the fact that MacCarthy published several volumes of well-received literary criticism, but this is seen as lacking a certain moral courage which genuinely creative writers face when they commit themselves to print. This is amusingly coupled to MacCarthy’s pathological procrastination and lack of self-discipline. a view echoed by Quentin Bell in his affectionate memoir of the MacCarthy family:

He would turn up at Richmond [Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s house] for dinner, uninvited very probably, and probably committed to a dinner elsewhere, charm his way out of his social crimes on the telephone, talk enchantingly until the small hours, insist that he be called early so that he might attend to urgent business on the morrow, wake up a little late, dawdle somewhat over breakfast, find a passage in The Times to excite his ridicule, enter into a lively discussion of Ibsen, declare he must be off, pick up a book which reminded him of something which, in short, would keep him talking until about 12.45, when he would have to ring up and charm the person who had been waiting in an office for him since 10, and at the same time deal with the complications arising from the fact that he had engaged himself to two different hostesses for lunch, and that it was now 1 o’clock, and it would take forty minutes to get from Richmond to the West End. In all this Desmond had been practising his art – the art of conversation.

He was knighted in 1951 and died in 1952. He was buried in Cambridge.

Bloomsbury Group – web links

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, featuring designs by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and others.

![]() The Omega Workshops

The Omega Workshops

A brief history of Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops, which had a lasting influence on interior design in post First World War Britain.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War

The Bloomsbury Group and War

An essay on the largely pacifist and internationalist stance taken by Bloomsbury Group members towards the First World War.

![]() Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Mini web site featuring photos, paintings, a timeline, sub-sections on the Omega Workshops, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, and biographical notes.

![]() Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Exhibition of paintings, designs, and ceramics at Toronto University featuring Hogarth Press, Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Quentin Bell, and Stephen Tomlin.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

A rich enthusiast site featuring news of events, exhibitions, new book reviews, relevant links, study resources, and anything related to Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search the texts of all Woolf’s major works, and track down phrases, quotes, and even individual words in their original context.

![]() A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

An annotated description of Clarissa Dalloway’s walk from Westminster to Regent’s Park, with historical updates and a bibliography.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Annotated tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury, including Gordon Square, University College, Bedford Square, Doughty Street, and Tavistock Square.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

News of events, regular bulletins, study materials, publications, and related links. Largely the work of Virginia Woolf specialist Stuart N. Clarke.

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

A charming sound recording of a BBC radio talk broadcast in 1937 – accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephens’ collection of family photographs which became known as the Mausoleum Book, collected at Smith College – Massachusetts.

![]() Bloomsbury at Duke University

Bloomsbury at Duke University

A collection of book jacket covers, Fry’s Twelve Woodcuts, Strachey’s ‘Elizabeth and Essex’.

© Roy Johnson 2000-2014

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was an artist and bohemian who loved and was loved by both men and women. She was born Dora de Houghton Carrington in Hereford, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. As a somewhat wilful youngster, she found her family background quite stifling, adoring her father and loathing her mother. She attended Bedford High School, which emphasized sports, music, and drawing. The teachers encouraged her drawing and her parents paid for her to attend extra art classes in the afternoons. In 1910 she won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and studied there with Henry Tonks.

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was an artist and bohemian who loved and was loved by both men and women. She was born Dora de Houghton Carrington in Hereford, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. As a somewhat wilful youngster, she found her family background quite stifling, adoring her father and loathing her mother. She attended Bedford High School, which emphasized sports, music, and drawing. The teachers encouraged her drawing and her parents paid for her to attend extra art classes in the afternoons. In 1910 she won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and studied there with Henry Tonks.

Dorothy Eugenie Brett was born November 10, 1883. She was the eldest daughter of the second Viscount Esher, Reginald Baliol Brett, who was the Liberal MP for Penryn and Falmouth. Her mother was Eleanor van de Weyer, the daughter of the Belgian ambassador to the court of St. James and a close advisor to Queen Victoria. She was called ‘Doll’ by her family, and like many upper class children of the Victorian era she was raised separately from her parents, receiving little formal education. She went to dancing classes with members of the royal family at Windsor Castle under the supervision of Queen Victoria, but had little contact with other children her own age, apart from her two elder bothers and younger sister sylvia who scandalised the family by becoming the

Dorothy Eugenie Brett was born November 10, 1883. She was the eldest daughter of the second Viscount Esher, Reginald Baliol Brett, who was the Liberal MP for Penryn and Falmouth. Her mother was Eleanor van de Weyer, the daughter of the Belgian ambassador to the court of St. James and a close advisor to Queen Victoria. She was called ‘Doll’ by her family, and like many upper class children of the Victorian era she was raised separately from her parents, receiving little formal education. She went to dancing classes with members of the royal family at Windsor Castle under the supervision of Queen Victoria, but had little contact with other children her own age, apart from her two elder bothers and younger sister sylvia who scandalised the family by becoming the

Duncan Grant (full name Duncan James Corrowr Grant) was born in Inverness, Scotland in 1885. He was brought up until the age of nine in India and Burma where his father was posted as an army officer. He returned to England in 1894 to attend school. While at St Paul’s school, London, he was brought up by his uncle and aunt Sir Richard and Lady Strachey (the parents of

Duncan Grant (full name Duncan James Corrowr Grant) was born in Inverness, Scotland in 1885. He was brought up until the age of nine in India and Burma where his father was posted as an army officer. He returned to England in 1894 to attend school. While at St Paul’s school, London, he was brought up by his uncle and aunt Sir Richard and Lady Strachey (the parents of

E.M.Forster is often seen as a bridge between the nineteenth and the twentieth century novel. He documents the Edwardian and Georgian periods in a witty and elegant prose, satirising the middle and upper classes he knew so well. He was a friend of Virginia Woolf, with whom he worked out some of the ground rules of literary modernism. These included the concept of what they called ‘tea-tabling’ – making the substance of serious fiction the ordinary events of everyday life. He was also an inner member of

E.M.Forster is often seen as a bridge between the nineteenth and the twentieth century novel. He documents the Edwardian and Georgian periods in a witty and elegant prose, satirising the middle and upper classes he knew so well. He was a friend of Virginia Woolf, with whom he worked out some of the ground rules of literary modernism. These included the concept of what they called ‘tea-tabling’ – making the substance of serious fiction the ordinary events of everyday life. He was also an inner member of  Where Angels Fear to Tread

Where Angels Fear to Tread Where Angels Fear to Tread – DVD This film version is not a Merchant-Ivory production, although it’s done very much in their style. But it is accurate and entirely sympathetic to the spirit of the novel, possibly even stronger in satirical edge, well acted, and superbly beautiful to watch. Much is made of the visual contrast between the beautiful Italian setting and the straight-laced English capital from which the prudery and imperialist spirit emerges. The lovely Helena Bonham-Carter establishes herself as the perfect English Rose in this her breakthrough production. Helen Mirren is wonderful as the spirited Lilia who defies English prudery and narrow-mindedness and marries for love – with results which manage to upset everyone.

Where Angels Fear to Tread – DVD This film version is not a Merchant-Ivory production, although it’s done very much in their style. But it is accurate and entirely sympathetic to the spirit of the novel, possibly even stronger in satirical edge, well acted, and superbly beautiful to watch. Much is made of the visual contrast between the beautiful Italian setting and the straight-laced English capital from which the prudery and imperialist spirit emerges. The lovely Helena Bonham-Carter establishes herself as the perfect English Rose in this her breakthrough production. Helen Mirren is wonderful as the spirited Lilia who defies English prudery and narrow-mindedness and marries for love – with results which manage to upset everyone. A Room with a View

A Room with a View A Room with a View – DVD This is a Merchant-Ivory production which takes one or two minor liberties with the original novel. But it’s still well acted, with the deliciously pouting Helena Bonham Carter as the heroine, Denholm Eliot as Mr Emerson, Daniel Day-Lewis as a wonderfully pompous Cecil Vyse, and Maggie Smith as the poisonous hanger-on Charlotte. The settings are delightfully poised between Florentine Italy and the home counties stockbroker belt. I’ve watched it several times, and it never ceases to be visually elegant and emotionally well observed. This film was nominated for eight Academy awards when it appeared, and put the Merchant-Ivory team on the cultural map.

A Room with a View – DVD This is a Merchant-Ivory production which takes one or two minor liberties with the original novel. But it’s still well acted, with the deliciously pouting Helena Bonham Carter as the heroine, Denholm Eliot as Mr Emerson, Daniel Day-Lewis as a wonderfully pompous Cecil Vyse, and Maggie Smith as the poisonous hanger-on Charlotte. The settings are delightfully poised between Florentine Italy and the home counties stockbroker belt. I’ve watched it several times, and it never ceases to be visually elegant and emotionally well observed. This film was nominated for eight Academy awards when it appeared, and put the Merchant-Ivory team on the cultural map. The Longest Journey

The Longest Journey Howards End

Howards End Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed.

Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed. A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece. A Passage to India – DVD This adaptation by David Lean is something of a mixed bag. It’s well organised, reasonably true to the original, and has some visually spectacular scenes. James Fox is convincing as the central character Fielding. But it has tonal inconsistencies, and to cast Alec Guinness as the Indian mystic Godbole is verging on the ridiculous. Nevertheless there is some good cameo acting, particularly Edith Evans as Mrs Moore. Watch out for the Indian signpost half way through that looks as if it’s made out of cardboard.

A Passage to India – DVD This adaptation by David Lean is something of a mixed bag. It’s well organised, reasonably true to the original, and has some visually spectacular scenes. James Fox is convincing as the central character Fielding. But it has tonal inconsistencies, and to cast Alec Guinness as the Indian mystic Godbole is verging on the ridiculous. Nevertheless there is some good cameo acting, particularly Edith Evans as Mrs Moore. Watch out for the Indian signpost half way through that looks as if it’s made out of cardboard. Maurice, (1967) is something from Forster’s bottom drawer. It was written in 1913-14, but not published until after his death. It’s an autobiographical novel of his gay university days which is explicit enough that couldn’t be published in his own lifetime. It’s light, amusing, and fairly inconsequential compared to the novels he wrote whilst pretending to be straight. This poses an interesting critical problem, when you would imagine he could have been more honest and therefore more successful.

Maurice, (1967) is something from Forster’s bottom drawer. It was written in 1913-14, but not published until after his death. It’s an autobiographical novel of his gay university days which is explicit enough that couldn’t be published in his own lifetime. It’s light, amusing, and fairly inconsequential compared to the novels he wrote whilst pretending to be straight. This poses an interesting critical problem, when you would imagine he could have been more honest and therefore more successful. Aspects of the Novel (1927) was originally a series of lectures on the nature of fiction. Forster discusses all the common elements of novels such as story, plot, and character. He shows how they are created, with all the insight of a skilled practitioner. Drawing on examples from classic European literature, he writes in a way which makes it all seem very straightforward and easily comprehensible. This book is highly recommended as an introduction to literary studies.

Aspects of the Novel (1927) was originally a series of lectures on the nature of fiction. Forster discusses all the common elements of novels such as story, plot, and character. He shows how they are created, with all the insight of a skilled practitioner. Drawing on examples from classic European literature, he writes in a way which makes it all seem very straightforward and easily comprehensible. This book is highly recommended as an introduction to literary studies. Collected Short Stories is like a glimpse into Forster’s workshop – where he tried out ideas for his longer fictions. This volume contains his best stories – The Story of a Panic, The Celestial Omnibus, The Road from Colonus, The Machine Stops, and The Eternal Moment. Most were written in the early part of Forster’s long career as a writer. Rich in irony and alive with sharp observations on the surprises in life, the tales often feature violent events, discomforting coincidences, and other odd happenings that throw the characters’ perceptions and beliefs off balance.

Collected Short Stories is like a glimpse into Forster’s workshop – where he tried out ideas for his longer fictions. This volume contains his best stories – The Story of a Panic, The Celestial Omnibus, The Road from Colonus, The Machine Stops, and The Eternal Moment. Most were written in the early part of Forster’s long career as a writer. Rich in irony and alive with sharp observations on the surprises in life, the tales often feature violent events, discomforting coincidences, and other odd happenings that throw the characters’ perceptions and beliefs off balance. E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.

E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.