diaries, journals, essays, and personal fragments

Lytton Strachey is best known through his letters, a voluminous outpouring which he maintained throughout his life. But those were written largely to amuse the recipients. This book gathers together his diaries, which he wrote in solitude for himself. It also contains autobiographical fragments, some travel journals, and two essays which were delivered to the Bloomsbury Memoir Club, plus occasional writings from periods of his life ranging from childhood to his last days. After a scene-setting opening which describes life at his family home at Lancaster Gate, the first entry is the journal of a holiday in Gibraltar, Cairo, and Capetown.

Then we get a confessional fragment on the first of his schoolboy love affairs, followed by a journal of his time studying literature at Liverpool University College. Next come reflections on Cambridge life and his preoccupations with sex, then an essay that records the events – or rather the thoughts and feelings – of a single day ‘Monday 16 June 1916’. This piece, written amidst the horrors of the first world war, conjures up a languorous, privileged visit to Vanessa Bell’s house at Charleston, doing virtually nothing the whole day long except lounge around in the garden, making plans to seduce the postman.

Then we get a confessional fragment on the first of his schoolboy love affairs, followed by a journal of his time studying literature at Liverpool University College. Next come reflections on Cambridge life and his preoccupations with sex, then an essay that records the events – or rather the thoughts and feelings – of a single day ‘Monday 16 June 1916’. This piece, written amidst the horrors of the first world war, conjures up a languorous, privileged visit to Vanessa Bell’s house at Charleston, doing virtually nothing the whole day long except lounge around in the garden, making plans to seduce the postman.

As Michael Holroyd admits in his linking commentary between the entries, this piece is guaranteed to infuriate Bloomsbury critics, but for those who are more sympathetic it offers a first-hand glimpse of what life was like amidst this group.

It’s also remarkably similar in style to Virginia Woolf’s poetic meditations and her shorter experimental fictions. It hovers tentatively in the regions of what we now call Proustian ‘moments’, and it is interesting to note that like the Lancaster Gate piece, it ends on a note of erotic confession.

This is a fairly lightweight compilation, but it fills in some gaps left by both the letters and the biography. Strachey is a fascinating character – far more complex than the picture of him as an effete neurasthenic which is commonly circulated.

© Roy Johnson 2005

Michael Holroyd (ed) Lytton Strachey by Himself, London: Abacus, 2005, pp.248, ISBN 0349118124

More on Lytton Strachey

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Mark Gertler (1896—1939) was born in Spitalfields in London’s East End, the youngest son of Jewish immigrant parents. When he was a year old, the family was forced by extreme poverty back to their native Galicia (Poland). His father travelled to America in search of work, but when this plan failed the family returned to London in 1896. As a boy he showed a marked talent for drawing, and on leaving school in 1906 he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic, which was the first institution in the UK to provide post-school education for working people.

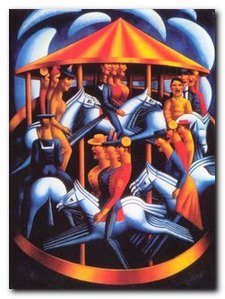

Mark Gertler (1896—1939) was born in Spitalfields in London’s East End, the youngest son of Jewish immigrant parents. When he was a year old, the family was forced by extreme poverty back to their native Galicia (Poland). His father travelled to America in search of work, but when this plan failed the family returned to London in 1896. As a boy he showed a marked talent for drawing, and on leaving school in 1906 he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic, which was the first institution in the UK to provide post-school education for working people. In 1914 he was also taken up by Edward Marsh an art collector who was later to become secretary to Winston Churchill. Even this relationship became difficult, since Gertler was a pacifist, and he disapproved of the system of patronage. He broke off the relationship, and around this time painted what has become his most famous painting – The Merry-Go-Round.

In 1914 he was also taken up by Edward Marsh an art collector who was later to become secretary to Winston Churchill. Even this relationship became difficult, since Gertler was a pacifist, and he disapproved of the system of patronage. He broke off the relationship, and around this time painted what has become his most famous painting – The Merry-Go-Round.

Phyllis and Rosamond for instance introduces many of the issues she explored in her later writings – the apparently empty lives of ordinary young women who went unrecognised by history; everyday life as a subject for fiction; the inequality of the sexes; and (almost as if Jane Austen were a contemporary) the ambiguous prospect of marriage as the only possible career structure for young females.

Phyllis and Rosamond for instance introduces many of the issues she explored in her later writings – the apparently empty lives of ordinary young women who went unrecognised by history; everyday life as a subject for fiction; the inequality of the sexes; and (almost as if Jane Austen were a contemporary) the ambiguous prospect of marriage as the only possible career structure for young females. In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and

Ottoline Morrell (1873-1938) features in the history of the

Ottoline Morrell (1873-1938) features in the history of the

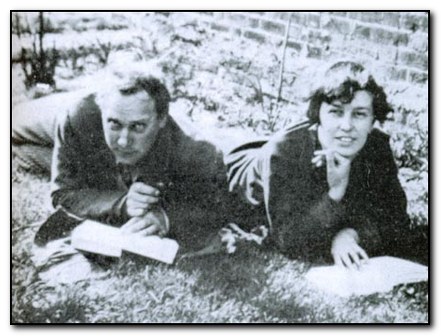

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.