intellectual, aesthete, enigma, and civil servant

Saxon Sydney-Turner (1880-1962) is one of the lesser-known and more enigmatic figures in the Bloomsbury Group. Very little is known about his life – largely because he took a lot of trouble to keep much of it private. His father was a doctor who ran a home for mental patients at Hove near Brighton. As a child he attended Westminster School in London and then went on in 1899 to Trinity College Cambridge. There he met Clive Bell, Leonard Woolf, and Thoby Stephen, who had all arrived the same year. He was on the same staircase as Clive Bell, and he later shared rooms with Leonard Woolf, who described him as ‘an absolute prodigy of learning’.

He was introverted and ferociously intellectual, and was rarely seen by day at Cambridge, since he rose late and stayed up reading late into the night. Together with his new friends he was elected as a member of the not-so-secret society the Apostles. This met late at night to discuss cultural and philosophic matters – all its members deeply influenced by the ideas of G.E.Moore and his Principia Ethica (1903). However, Saxon Sydney-Turner is mainly remembered for his silences rather than any positive contribution to the debates.

He was interested in poetry, painted a little, and was a music lover with an especial liking for opera. He regularly attended the Wagner Ring cycles at Bayreuth. He loved puzzles, crosswords, riddles, and acrostics, and won one of the scholarships in Classics because he was able to identify and solve a riddle in the centre of an obscure Greek text which was set for translation.

In his finals he took a double first and did well enough in the Civil Service exams to gain a choice opening as a civil servant in the Treasury. He moved into the job and stayed there, working in obscurity for the rest of his life. Through his friendships with Leonard and Thoby, he became an accepted part (though a peripheral figure) in the Bloomsbury Group, though his reputation as an intellectual intimidated some of its members, and he sometimes exasperated his more outgoing contemporaries because he might turn up as one of their causeries, stay for sixteen hours, and say nothing.

He was modest, unassuming, and kind, but despite his formidable erudition people found him slightly infuriating because of his lack of drive and motivation. His friend Leonard Woolf described him as ‘an eccentric in the best English tradition who wrote elegant verse and music and possessed an extraordinary supple, and enigmatic mind’. And yet –

The rooms in which Saxon lived for many years in Great Ormond Street consisted of one big sitting room and a small bedroom. On each side of the sitting-room fireplace on the wall was an immense picture of a farmyard scene. It was the same picture on each side and for over thirty years Saxon lived with them for ever before his eyes while in his bedroom there were some very good pictures by Duncan Grant and other artists, but you could not possibly see them because there was no light and no space to hang them on the walls.

Unlike many of his Bloomsbury friends, he was not at all sexually active. He did fall in love with Barbara Hiles, a former Slade student who was a friend of Dora Carrington. When she revealed that she was going to marry Nick Bagenal but could retain Saxon as a potential lover, he wrote to say that he felt unable to share her with somebody else. However, he did manage to reconcile himself to the loss and remained a close friend to Barbara Hiles and her children – indeed the friendship lasted longer than the Bagenal’s marriage.

When Lytton Strachey moved into the Mill House at Tidmarch with Dora Carrington, Saxon had a £20 a year stake in it for occasional use, though Gerald Brenan‘s account of his visits there illustrates why he described him as ‘one of the greatest bores I have ever known’.

he took to going every summer to Finland, coming back each time with a collection of snapshots that showed nothing but fir trees of varying heights and small railway stations. When he arrived at Lytton Strachey’s house for the weekend he would bring these photographs with him and one dreaded the moment when he would fetch them out and display them one by one, very slowly, in that muffled yet persistent voice of his, with brief comments: ‘I took that one of a railway station in the tundra because when I first went to Finland it had not been built.’

In later life developed a weakness for the horses – though he never went to any races. He gambled away almost all his modest savings and was forced to scrounge from neighbours for essentials. He ended his days in a small flat where he watched television on a set purchased for him by friends.

Bloomsbury Group – web links

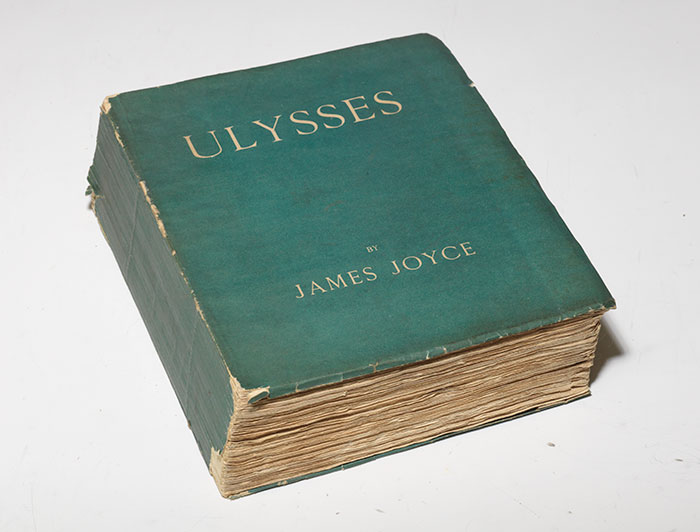

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, featuring designs by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and others.

![]() The Omega Workshops

The Omega Workshops

A brief history of Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops, which had a lasting influence on interior design in post First World War Britain.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War

The Bloomsbury Group and War

An essay on the largely pacifist and internationalist stance taken by Bloomsbury Group members towards the First World War.

![]() Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Mini web site featuring photos, paintings, a timeline, sub-sections on the Omega Workshops, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, and biographical notes.

![]() Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Exhibition of paintings, designs, and ceramics at Toronto University featuring Hogarth Press, Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Quentin Bell, and Stephen Tomlin.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

A rich enthusiast site featuring news of events, exhibitions, new book reviews, relevant links, study resources, and anything related to Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search the texts of all Woolf’s major works, and track down phrases, quotes, and even individual words in their original context.

![]() A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

An annotated description of Clarissa Dalloway’s walk from Westminster to Regent’s Park, with historical updates and a bibliography.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Annotated tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury, including Gordon Square, University College, Bedford Square, Doughty Street, and Tavistock Square.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

News of events, regular bulletins, study materials, publications, and related links. Largely the work of Virginia Woolf specialist Stuart N. Clarke.

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

A charming sound recording of a BBC radio talk broadcast in 1937 – accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephens’ collection of family photographs which became known as the Mausoleum Book, collected at Smith College – Massachusetts.

![]() Bloomsbury at Duke University

Bloomsbury at Duke University

A collection of book jacket covers, Fry’s Twelve Woodcuts, Strachey’s ‘Elizabeth and Essex’.

© Roy Johnson 2000-2014

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

It’s a work that skillfully combines real-life biographical studies, their reflection in imaginative fiction, plus a mercifully light dusting of historical and sociological statistics. Nicholson has selected her illustrative examples from as wide a social range as possible, but those which stand out are inevitably the middle and upper class women who have left a written record of their experiences.

It’s a work that skillfully combines real-life biographical studies, their reflection in imaginative fiction, plus a mercifully light dusting of historical and sociological statistics. Nicholson has selected her illustrative examples from as wide a social range as possible, but those which stand out are inevitably the middle and upper class women who have left a written record of their experiences.

From 1890 onwards the Kodak portable camera was both heavily promoted and enthusiastically taken up by female amateurs. Virginia and Vanessa took the photographs, developed them, printed them, and mounted them in albumns. And the Stephen sisters were not alone in their activity. Many of the other

From 1890 onwards the Kodak portable camera was both heavily promoted and enthusiastically taken up by female amateurs. Virginia and Vanessa took the photographs, developed them, printed them, and mounted them in albumns. And the Stephen sisters were not alone in their activity. Many of the other

Bloomsbury Recalled

Bloomsbury Recalled The Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900—1930

Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900—1930 Portrait of a Marriage

Portrait of a Marriage