tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

An Outcast of the Islands (1896) is Joseph Conrad’s second novel, following closely on his first, Almayer’s Folly which was published the previous year. In fact An Outcast has a close relationship to Almayer, because it deals with some of the same characters and events.

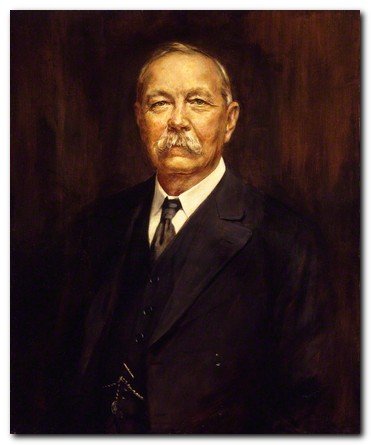

Joseph Conrad

In fact it is part of what might be called a ‘trilogy in reverse’. An Outcast deals with events that take place in 1872, whereas Almayer’s Folly is set about 1887. An Outcast provides what might in modern media terms be called a ‘back story’ to the first novel. There is also a third volume in the series called The Rescue that deals with events set even earlier in the 1850s – but this was not published until 1920.

Conrad first conceived An Outcast as a short story called Two Vagabonds, but like many of his planned fictions it expanded as soon as he started writing it.

An Outcast of the Islands – plot summary

Peter Willems is a conceited bully who works as a ‘confidential’ clerk for Hudig & Co in Macassar in Malaysia. He has secured the job through the kindness of Tom Lingard, a sea captain who has rescued him as a youth. As the story opens, Willems is embezelling money of Hudig’s to finance a deal he hopes will make him a partner in the company.

But Willems’ illegal doings are revealed, and he is expelled by Hudig, who has only tolerated Willems because he was prepared to marry his daughter. Willems is on the point of complete despair when Lingard sails into port, bails him out financially, and recruits him to work in a commercial outpost at Sambir where he has commercial dominance. However, Willems does not get on with Almayer, the chief at the outpost. He is also unaware of a plot to cause trouble being hatched by Babalatchi, a louche character at the outpost. Willems is sinking back towards despair when he meets a young woman Aissa and is completely overwhelmed by her beauty. He leaves the outpost and goes to live with her and her blind father, Omar.

But Willems’ illegal doings are revealed, and he is expelled by Hudig, who has only tolerated Willems because he was prepared to marry his daughter. Willems is on the point of complete despair when Lingard sails into port, bails him out financially, and recruits him to work in a commercial outpost at Sambir where he has commercial dominance. However, Willems does not get on with Almayer, the chief at the outpost. He is also unaware of a plot to cause trouble being hatched by Babalatchi, a louche character at the outpost. Willems is sinking back towards despair when he meets a young woman Aissa and is completely overwhelmed by her beauty. He leaves the outpost and goes to live with her and her blind father, Omar.

Five weeks later he returns to Almayer with the warning that plots are being hatched against the trading outpost. He asks Almayer for a loan to set up as an independent trader – a request that Almayer scornfully refuses, correctly surmising that Willems has been expelled from Hudig & Co for embezellement.

Meanwhile Babalatchi conspires with Omar against Willems, plotting to bring in outside help from rich trader Abdulla, who wishes to displace Lingard in the area. Abdulla visits Sambir, and is negatively briefed by Babalatchi Abdulla negotiates with Omar and with Willems (who he knows from Hudig & Co) and leaves with plans to return two days later.

Willems feels trapped and humiliated by his overwhelming desire for Aissa and despairs because he realises they are from completely different cultures. Aissa wish to know what has passed between Willems and Abdulla. She is conscious of her power over him but resents the trouble he brings as an outsider.

Willems has the sole objective of running away with Aissa but she refuses. Whilst they are consoling each other Omar attempts to kill Willems and it seems to Willems as if the daughter might even be helping him.

Almayer gives Captain Lingard a lengthy and somewhat confused account of Abdulla’s attack on the trading post. There is a conflict caused by both Dutch and British flags being raised over the outpost. All Almayer’s gunpowder is thrown into the river and Willems has Almayer sewn into his own hammock, before making off.

Captain Lingard has lost his ship Flash and proposes a new scheme for prospecting upriver for alluvial gold. He has brough Willems’ wife and child to Sambir, still feeling he has a responsibility for them.

Lingard is smarting from the unusually bad state of his affairs (lost ship, lost supremacy on the river). He receives notes of invitation from both Willems and Abdulla. Almayer urges him to act against their rivals.

Lingard arrives in Sambir apparently with the intention of killing Willems. He is met by Babalatchi, who urges him against Willems. Then he is intercepted by Aissa, who is distraught because Willems has become distant from her.

When Lingard confronts Willems, he punches him severely, but thinks he is not worth shooting. Willems wants Lingard to ‘rescue’ him from his plight. But Lingard does the opposite – and condemns him to remain in permanent exile with Aissa. He regards Willems as his ‘mistake’, and his ‘shame’.

Almayer feels a rancorous anxiety at what he sees as Lingard’s tolerant attitude to Willems, and he is apprehensive about his own position. He thinks of killing Willems, but then persuades Mrs Willems to ‘rescue’ her husband. He then sets off with a group of men in a boat, which through his ineptness runs aground.

Willems feels an existential dread at having been abandoned by Lingard. He thinks of himself as deracinated, cut off from all civilized help, and without any human resources to survive the ordeal – even though he has Aissa with him and Lingard is supplying him with food. Eventually his wife Joanna arrives with their son. Willems feels doubly oppressed and thinks of killing both women – but Aissa gets to the gun first and shoots him.

Study resources

![]() An Outcast of the Islands – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

An Outcast of the Islands – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() An Outcast of the Islands – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

An Outcast of the Islands – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() An Outcast of the Islands – Kindle eBook

An Outcast of the Islands – Kindle eBook

![]() An Outcast of the Islands – DVD film adaptation at Amazon UK

An Outcast of the Islands – DVD film adaptation at Amazon UK

![]() An Outcast of the Islands – eBook at Project Gutenberg

An Outcast of the Islands – eBook at Project Gutenberg

![]() Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

![]() An Outcast of the Islands – DVD film adaptation at MovieMail

An Outcast of the Islands – DVD film adaptation at MovieMail

![]() An Outcast of the Islands – film details at IMD

An Outcast of the Islands – film details at IMD

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Principal characters

| Peter Willems | a Dutch confidential clerk at Hudig & Co |

| Joanna da Souza | his wife – a half-caste |

| Louis Willems | his pasty son |

| Leonard da Souza | his brother-in-law |

| Mr Vinck | cashier at Hudig & Co |

| Tom Lingard | an experienced sea captain with a monopolistic knowledge of river navigation |

| Kaspar Almayer | Lingard’s Dutch business partner, married to his adopted daughter |

| Babalatchi | a one-eyed vagabond |

| Lakamba | trader-cultivator and war-lord |

| Patalolo | local leader in Sambir |

| Omar el Badavi | blind Arab chief |

| Aissa | his beautiful daughter |

| Sambir | trading post town in Borneo |

| Syed Abdulla bin Selim | prosperous Muslim trader and distant relative of Omar |

| Nina | Almayer’s child |

| Ali | Almayer’s Malaysian assistant |

Biography

Setting

The first part of the novel is set in Macassar, a provincial capital in southern Indonesia. The remainder and majority of the events take place in the fictional town of Sambir, which is losely based on Berau in north-east Borneo (today called Kalimantan) very close to the equator.

The river Pantai on which it is based plays an important part in the story. Captain Lingard has established his prosperous trading business based on his monopoly of navigational skills on the river which is the source of much annoyance to his business rivals.

first edition – New York, D. Appleton, 1896

Further reading

![]() Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

![]() Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

![]() John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

![]() Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

![]() Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

![]() Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

![]() Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

![]() George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

![]() James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

![]() John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

![]() Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

Joseph Conrad’s writing table

Other works by Joseph Conrad

Under Western Eyes (1911) is the story of Razumov, a reluctant ‘revolutionary’. He is in fact a coward who is mistaken for a radical hero and cannot escape from the existential trap into which this puts him. This is Conrad’s searing critique of Russian ‘revolutionaries’ who put his own Polish family into exile and jeopardy. The ‘Western Eyes’ are those of an Englishman who reads and comments on Razumov’s journal – thereby creating another chance for Conrad to recount the events from a very complex perspective. Razumov achieves partial redemption as a result of his relationship with a good woman, but the ending, with faint echoes of Dostoyevski, is tragic for all concerned.

Under Western Eyes (1911) is the story of Razumov, a reluctant ‘revolutionary’. He is in fact a coward who is mistaken for a radical hero and cannot escape from the existential trap into which this puts him. This is Conrad’s searing critique of Russian ‘revolutionaries’ who put his own Polish family into exile and jeopardy. The ‘Western Eyes’ are those of an Englishman who reads and comments on Razumov’s journal – thereby creating another chance for Conrad to recount the events from a very complex perspective. Razumov achieves partial redemption as a result of his relationship with a good woman, but the ending, with faint echoes of Dostoyevski, is tragic for all concerned.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Chance is the first of Conrad’s novels to achieve a wide commercial success, and one of the few to have a happy ending. It tells the story of Flora de Barral, the abandoned daughter of a bankrupt tycoon, and her long struggle to find happiness and dignity. He takes his techniques of weaving complex narratives to a challenging level here. His narrator Marlow is piecing together the story from a mixture of personal experience and conversations with other characters in the novel. At times it is difficult to remember who is saying what to whom. This is a work for advanced Conrad fans only. Make sure you have read some of the earlier works first, before tackling this one.

Chance is the first of Conrad’s novels to achieve a wide commercial success, and one of the few to have a happy ending. It tells the story of Flora de Barral, the abandoned daughter of a bankrupt tycoon, and her long struggle to find happiness and dignity. He takes his techniques of weaving complex narratives to a challenging level here. His narrator Marlow is piecing together the story from a mixture of personal experience and conversations with other characters in the novel. At times it is difficult to remember who is saying what to whom. This is a work for advanced Conrad fans only. Make sure you have read some of the earlier works first, before tackling this one.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Victory (1915) is set in the legendary port of Surabaya and in an outpost of the Malayan archipelago. It is the story of Swedish recluse Axel Heyst, who rescues Lena, a young woman from a touring orchestra and runs off to live in remote seclusion, influenced by the pessimistic philosophy of his father. But he is pursued by two lying and scheming English gamblers, who believe he is concealing ill-gotten wealth. They corner him in his retreat, and despite the efforts of Lena to shield Heyst from their plans, there is a tragic confrontation which brings destruction into their island paradise.

Victory (1915) is set in the legendary port of Surabaya and in an outpost of the Malayan archipelago. It is the story of Swedish recluse Axel Heyst, who rescues Lena, a young woman from a touring orchestra and runs off to live in remote seclusion, influenced by the pessimistic philosophy of his father. But he is pursued by two lying and scheming English gamblers, who believe he is concealing ill-gotten wealth. They corner him in his retreat, and despite the efforts of Lena to shield Heyst from their plans, there is a tragic confrontation which brings destruction into their island paradise.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2012

Joseph Conrad links

![]() Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

![]() Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

![]() Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

![]() Works by Joseph Conrad

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society of America

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

![]() Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

More on Joseph Conrad tales

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism. Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. Best-selling title, written by the author of these web pages.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. Best-selling title, written by the author of these web pages.

The term theme is used to describe the underlying topic or issue of the narrative. This is often of a general or abstract nature, as distinct from the overt subject with which the work deals. It should be possible to express theme in a single word or short phrase such as ‘redemption through suffering’, ‘moral education’, or ‘coming of age’.

The term theme is used to describe the underlying topic or issue of the narrative. This is often of a general or abstract nature, as distinct from the overt subject with which the work deals. It should be possible to express theme in a single word or short phrase such as ‘redemption through suffering’, ‘moral education’, or ‘coming of age’.

A famous and much-discussed example is Joseph Conrad’s novella

A famous and much-discussed example is Joseph Conrad’s novella